The trade in fermented beverages and the duties to be paid.

The empire Maurya puts an end to the multitude of kingdoms, chieftaincies and internecine wars in India. It creates for the first time in South Asia a vast political entity with relative military security and a unified political system. The army fights against bandits, regional private armies and powerful local warlords. This new peace and organisation promotes agriculture, trade and commerce. Chandragupta Maurya imposes a currency and an imperial system of weights and measures. The territory is squared by administrators in charge of collecting taxes and settling disputes between farmers, merchants and traders. The dynasty of the Mauryas organised major works (roads, canals, drainage, fortifications, ...) to promote the economic exchanges and control its territory. The merchant organisations were the big winners of this new economic policy.

At the regional level, the economic policy of the Maurya stimulates the production and trade of beer, according to the content of the Treaty which favours this trade:

« By employing such men as are acquainted with the manufacture of fermented beverages (surā) and brewing ferments (kinva), the Superintendent of Sura shall carry on liquor-traffic not only in forts and country parts, but also in royal camps. " (Book II, chap. 25). These camps are fortified imperial towns scattered over all the empire territory to better control it.

Don't imagine a pre-industrial brewery in India 2200 years ago!

The beer production remains a small-scale craft. The " specialist in the making of surā and ferments " is a man or a woman who buys grains and plants, makes a few jars of beer, sells them in a tavern or a market, and starts again when the jars are empty. The beer is brewed in small quantities with local cereals and sold in taverns/inns. It can only be inferred from a few paragraphs of the Treaty that this local production is bought by professional traders who are able to transport the beer and sell it elsewhere to increase their profit.

The Book V, chap. 2 of the Arthashastra entitled " Reconstitution of the Treasury " sets the tone. The empire organises the territory and ensures security, and in its turn any productive or mercantile activity contributes to the growth of the imperial treasury. Not a domain remains forgotten. The Reconstitution of the Treasury speaks of the big merchants organised in merchant associations and of the small local merchants. The former deal with the most expensive goods (precious stones and metals, horses, elephants, ...).

The second are involved at the regional or local level in selling food products (grains, cooked rice, food, firewood, small crafts, etc.). Among them are the beer merchants. The Arthashastra mentions the direct link between the trade of grains and that of beer :

« Merchants dealing with gold, silver, diamonds, precious stones, pearls, coral, horses and elephants shall pay 50 karas. Those that trade in cotton thread, clothes, copper, brass, bronze, sandalwood, medicines and fermented beverages shall pay 40 karas. Those that trade grains, liquids, metal (loha), and deal with carts shall pay 30 karas. Those that carry on their trade in glass (kâcha); and also artisans of fine workmanship shall pay 20 karas. Articles of inferior workmanship, as well as those who keep prostitutes, shall pay 10 karas. Those that trade in firewood, bamboo, stones, pottery, cooked rice and vegetables shall pay 5 kara. Dramatists and prostitutes shall pay half of their wages. The entire property of goldsmiths shall be taken possession of; and no offence of theirs shall be forgiven; for they carry on their fraudulent trade while pretending at the same time to be honest and innocent. So much about demands on merchants. » (Book V, chap. 2).

The text does not specify whether the right to brew and sell beer (amounted 40 karas) is paid annually or not, and whether it is granted for a region, a province or the entire empire.

The fate done to the artisan goldsmiths is dreadful. The Arthashastra specifies elsewhere that goldsmithing becomes an activity controlled by the imperial administration which will benefit from it. Independent craftsmanship is banned from this activity.

The fees paid by the brewers and the beer merchants is heavy (40 karas, the maximum is 50 karas, those who sell grain only pay 30 karas). The beer merchants belong to the same category as those which sell medicine, utility metal, cotton and weavings. One could detect in this tariff the moral orientation of the Treaty, which regards the fermented beverages as a source of social and political disorder that must be combated and therefore heavily taxed. However, this category of the imperial tax tariff encompasses medicines and surā, both grain and herbal preparations. This means that their trade is not only joined but also carried out on a regional scale. The right to sell beer is high because it implies a regional circulation of grains, plants, by-products and fermented beverages. The beer trade targeted by this category of imperial fees is not relevant of the small-scale village trade. Hence, the imperial economic realism prevails over Hindu morality.

In other words, the beer bought by merchants is sold at a great distance. It is stored and carried in earthenware jars. We will see later on that the spices and plants introduced into the brewing process serve to preserve the beer as well as to enrich its flavours. Very elaborate brewing techniques have favoured the beer trade and consequently the imperial fiscal policy of the Maurya. This applies to beers made with amylolytic ferments, a brewing method that increases the alcohol content (approx. 10% vol.), not to other traditional beers made from barley or millet malt, which seldom exceed an alcohol content of 4%-5% in those times.

The imperial administrators designate the manufacturers and merchants of fermented beverages who are entitled to brew and sell the beer. These can do their business, provided they have to pay 40 karas. They will later have to pay the treasury a tax of 5% of the price of their sales. The imperial policy favours the beer production and the widespread trade of beer. Brewers (perhaps also female brewers) and beer merchants must have access to every places where beer can be sold (cities, military forts, royal camps), in return for the payment of duties to the imperial treasury :

« By employing such men as are acquainted with the manufacture of beer and ferments (kinva), the Superintendent of Sura shall carry on beer-traffic not only in forts and country parts, but also in royal camps.

In accordance with the requirements of demand and supply (krayavikrayavasena), he may either centralise or decentralise the sale of surā.

A fine of 600 panas shall be imposed on all offenders other than those who are manufacturers, purchasers, or sellers in beer-traffic.

Beer shall not be taken out of villages, nor shall beer shops be close to each other. » (Book II, chap. 25).

The Arthashastra defines three categories of territory where the production and sale of fermented beverages is authorised or even favoured as a source of income:

1) countryside and villages.

2) the military garrison forts.

3) the itinerant camps of the imperial, provincial and regional courts, which resemble, as will be seen below, real cities.

This classification emanates from a central power concerned with three different modes of beer production and consumption, three social spheres, but also three strategies for collecting taxes. These adapt to the territorial constraints and customs of the people living there. We review these three types of territories under the control of the empire, from the point of view of the management of beer and brewing.

The countryside first. Seen from the imperial court, the rural world is an undifferentiated assemblage of fields, forests, marshes and villages. The farmers' beer is linked to agrarian rites, village festivities, family or collective rituals that punctuate the cycle of human life (birth, puberty, marriage, death). How can we keep an eye on everything that is brewed and drunk in each village? The Arthashastra gives its instructions to the tax collector :

1) he must watch at fairs and markets where domestic beers are consumed :

" With regard to surā, medaka, arishta, wine, phalámla (acid drinks prepared from fruits), and ámlasídhu : Having ascertained the day's sale of the above kinds of surā, the difference of royal and public measures (mánavyáji), and the excessive amount of sale proceeds realised thereby, the Superintendent shall fix the amount of compensation (vaidharana) due to the king (from local or foreign merchants for entailing loss on the king's sura traffic) and shall always adopt the best course. »

2) it must authorise only 4 days of beer brewing for religious and family festivals celebrated in the villages:

« On special occasions (krityeshu), people (kutumbinah, i.e., families) shall be allowed to manufacture white beer (svetasura), arishta for use in diseases, and other kinds of surā. On the occasions of festivals, fairs (samája), and pilgrimage, right of manufacture of beer for four days (chaturahassaurikah) shall be allowed. The Superintendent shall collect the daily fines (daivasikamatyayam, i.e., license fees) from those who on these occasions are permitted to manufacture surā. »

3) he must put spies in the taverns where the beer-surā is brewed and sold (Arthashastra Book 5 chap. 2.2).

4) he must have make the drinking areas signposted with a highly visible flag sign (Arthashastra Book 5 chap. 2.2).

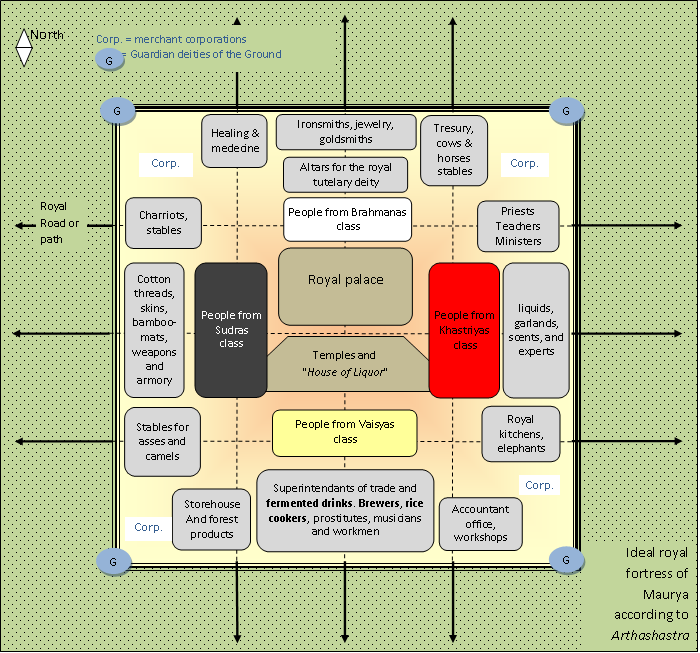

The fortresses The fortresses embody the imperial military presence. In the garrisons, beer-surā becomes a fermented beverage devoted to the warriors. It is related to the courage, valour and power of Indra. It is the social drink of the Aryas, and that of the soldiers (kshatriyas) in the service of the empire. Inside the fortresses and the new cities (the Maurya founded many of them), there is a sharp spatial partition between the Brahmins who live in the town northern districts, the soldiers (class of the Kshatriyas) who live in the town eastern part, and the humble people of the sura traders and makers (class of the Vaisyas) who live in the town southern part:

« To the south, the superintendents of the city, of commerce, of manufactories, and of the army as well as those who trade in cooked rice, sura-beer, and flesh, besides prostitutes, musicians, and the people of Vaisya caste shall live ».(Livre II chap. 4, Bâtiments à l’intérieur d’un fort) [1].

Diagram of a fortified city as described by the Arthashastra. The plan is geometrical. 4 districts are located at the cardinal corners. Brewers and beer merchants live with the craftsmen. They occupy the southern district of the city, supervised by the Superintendent of fermented beverages (surā).

We deduce from this device that brewers and beer merchants belong to the Vaisya caste of farmers, craftsmen and merchants. This seems to be self-evident since beer is above all a drink made from the grain harvests (rice, barley, millet). But the ungrateful tasks of brewing remain devolved to the Sudras (caste of servants, labourers and slaves): grind the grains, collect the water, the firewood, etc. [2]. The willingness to promote the beer trade and collect the beer taxes in the fortified towns is stated in the following way:

« Tolls, fines, weights and measures, the town-clerk (nágaraka), the superintendent of coinage (lakshanádhyakshah), the superintendent of seals and passports, of sura-beer, slaughter of animals, threads, oils,. ghee, sugar (kshára), the state-goldsmith (sauvarnika), the warehouse of merchandise, the prostitute, gambling, building sites (vástuka), the corporation of artisans and handicrafts-men (kárusilpiganah), the superintendent of gods, and taxes collected at the gates (of the town) and from the people (known as) Báhirikas come under the head of forts. »(Book II, chap. 6 Business of collection of revenue by the collector-general).

The itinerant royal courts, finally, are the economic and organizing power of the empire. Within them the largest share of the most varied fermented beverages is consumed. It is the domain of superintendents, courtiers and power struggles. The 4 great imperial provinces are ruled by a prince surrounded by his own court. Here the regional cultures of the empire and the different drinking manners are expressed. This is why the Arthashastra lists all the fermented beverages it may know. Some of them are regional, such as the palm or sugar cane wines of southern India, or the grape wine of the westernest province which experienced the Greek influence of Alexander's army. Beer alone is present in all the provinces, but in different forms: barley beers in the west, rice and millet beers in the Ganges valley and in the eastern part of the empire (see Beer inventory in the times of Arthasastra).

The religious buildings are located in the centre of the cities:

« In the centre of the city, the apartments of Gods such as Aparájita, Apratihata, Jayanta, Vaijayanta, Siva, Vaisravana, Asvina (divine physicians), and the honourable liquor-house (Srí-madiragriham), shall be situated. ».

Alongside the countryside, the military forts and the encampments of the provincial courts, there is no indication for the imperial capital Pataliputra on the banks of the Ganges. It is one of the largest and most brilliant cities in the world at that time [3]. The imperial government seats there, when the king does not roam his vast empire nor lead a war. Foreign delegations and great merchants converge there. Fermented beverages of all kinds are flowing here. Manufacturers and sellers of surā are taxed at 5%, except those who serve the king, those who supply the imperial court. The imperial court is not taxed for its consumption of fermented beverages. This is undoubtedly what the expression " other than those of the king " means whenever the Arthashastra speaks of levying taxes on the beer-sura. Some brewers and beer merchants work for the royal courts. The imperial treasury does not tax itself!

Those who brew or sell without authorisation are fined 600 panas. Chap. 19 of the Weights and Measures sets at 1¼ pana the price of one drona of beverage (i.e. 13.2 kg). According to this table, 600

The empire follows the same policy in almost all economic activities. The prohibitive fine imposed on brewers and beer sellers who have not been selected by the superintendence and have not paid 40 karas drives out the occasional brewers from the villages and countryside, the women brewers engaged in local trade, the domestic beer shared between neighbours, etc. In short, the imperial administration monopolises all economic activities and certain socialised forms of sharing, especially beer. Fermented beverages are taxed in two ways:

- the tax-collector of the king collects 5% of the sale price of beer, "Those who trade with the Sura, other than those of the king, must pay 5% tax." Book II, chapter 25.

- the responsible of customs takes a fee in kind of 1/20th (or 1/25th) on all drinks entering or leaving a city or fortress. These fermented beverages are mostly beers, as shown by the close relationship that the text establishes between the trade in fermented beverages and the cooked rice sale :

« ... of sandal, brown sandal(agaru), pungents (katuka), brewing ferments (kinva), dress (ávarana), and the like; of wine, ivory, skins, raw materials used in making fibrous or cotton garments, carpets, curtains (právarana), and products yielded by worms (krimijáta); and of wool and other products yielded by goats and sheep, he shall receive 1/10th or 1/15th as toll. Of cloths (vastra), quadrupeds, bipeds, threads, cotton, scents, medicines, wood, bamboo, fibres (valkala), skins, and clay-pots; of grains, oils, sugar (kshára), salt, liquor (madya), cooked rice and the like, he shall receive 1/20th or 1/25th as toll. » (Book II, chap. 22 : Regulation of toll-dues).

[1] The 4 varnas (castes): Brahmanas (priests, wise men and officials), Kshatriyas (warriors and rulers), Vaysias (farmers, craftsmen and merchants), Sudras (servants, labourers, male and female slaves, all-purposes men and women labor).

[2] A tricky problem arises here. At what technical stage could beer, whose brewing ingredients passed through the impure hands of the lesser class Sudras, be regarded as pure and fit to be drunk by the higher castes of the Kshatriyas (excepted Brahmins)? After the magical fermentation ? After a purifying blessing ?

[3] " According to Megasthenes the mean breadth (of the Ganges) is 100 stadia (1850 m), and its least depth 20 fathoms (37 m). At the meeting of this river and another is situated Palibothra, a city eighty stadia (14,8 km) in length and fifteen (2,7 km) in breadth. It is of the shape of a parallelogram, and is girded with a wooden wall, pierced with loopholes for the discharge of arrows. It has a ditch in front for defence and for receiving the sewage of the city.” (Strabon XV. i. 35-36). It is assumed that Megasthenes was using the attic stadion unit (185 m), not the babylonian-persian stadion (196 m). 1 mile = 4500 pouss = 4500 * 0.308 m = 1386 m. So 1 attic stadion = 15/2 mile = 185 m.