The first granaries and the first beer brews.

Neolithic sites in the dry regions of the world are known for their grain storage structures. The Near East, Central Asia, North Africa and the Sahel, the Andean Cordillera, northern Mexico offer multiple examples of buried jars, coated cavities used to store grain, raised structures made of adobe or beaten earth used as granaries. A food storage facility dating from 11,000 BC, i.e. before the domestication of cereals, has been discovered in the Jordan Valley[1].

Humid tropical areas do not have such structures: the tubers are hydrated, unlike the caryopses of grasses. They are collected all year round and keep better sunk in the ground than uprooted and quickly putrescible. The stocks are in the soil of the cleared forest, areas of slash-and-burn land fertilised for horticulture, not in the villages locked up in jars or silos.

The following explanations therefore apply to cereal farmers, human groups subject to the constraints of the annual or semi-annual harvest (rice, millet, wheat, barley, ...) that need to be stored. These cultural centres coincide with the alluvial basins of large rivers and the domesticated cereals of these regions: Tigre and Euphrates, Nile and Niger, Indus, Ganges and Brahmaputra, Huang-He and Yangze, Mekong, Mississippi-Missouri, etc. The following protohistoric sequences therefore apply only to the civilisations that these fertility basins fed and watered.

Other models are needed to explain the history of beer brewing among peoples and civilizations based on the horticulture of starchy plants (cassava, yams, sweet potatoes, taro, etc.). This history is as rich and ancient as that of the cereal growers. Beer also holds a central role among the world's horticultural peoples who live in the tropical regions, a very wide belt on either side of the equator (Amazonia, Guianas, Central America, tropical Africa, monsoon Asia, Indonesia, etc.).

The first grain surpluses in the villages of Oueili and Samarra.

The Ubaid culture owes its name to the southern Mesopotamian site of Tell el Ubaid near Ur and is typified by a tripartite architecture (rooms arranged in three parallel bays) and painted ceramics with black decorations on beige paste. Its expansion affected a large part of the Near East, involving far-reaching changes. The Ubaid period owes its name to the village culture of the same name and extends from the middle of the 7th millennium to the end of the 5th millennium B.C. It is divided into six phases. Only phases 3 and 4 are present in northern Mesopotamia:

- Ubaid 0 (6400-6000 av. J.-C)

- Ubaid 1 (6000-5600)

- Ubaid 2 (5600-5300)

- Ubaid 3 (5300-4800)

- Ubaid 4 (4800-4400)

- Ubaid 5 (4400-4000)

Source : Ubaid, techniques de conservation

The very long period of Ubaid began around 6500 on the shores of the Persian Gulf. The Neolithic villages are egalitarian social structures. People manage matters jointly, they gather in collective buildings. The habitat of the 7th millennium, relatively uniform, reflects the equality of the conditions of existence. The tombs, domestic furniture and habitat do not show any material or ornamental differentiation. Within small communities and among scattered populations, no one monopolises tools, land or water. The uninhabited territories absorb the very slow population growth without hindrance or conflict.

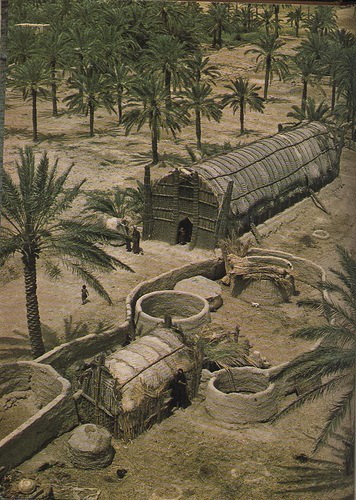

The village of Oueili, among hundreds of hamlets still buried under the silt of the Tigris and Euphrates rivers, reports the modest beginnings of the region's farming communities, among the oldest in the world with the Hebei communities in China. They exploit this moist but hospitable southern Iraqi, at a time when the Tigris-Euphates delta has not yet turned into vast swamps. Bearers of the same technical assets as the contemporary culture of Samarra (6200-5700) which flourished in Central Mesopotamia, the Ubaidian groups built their collective houses in moulded bricks. One of them is divided into rooms and occupies more than 240 m2.

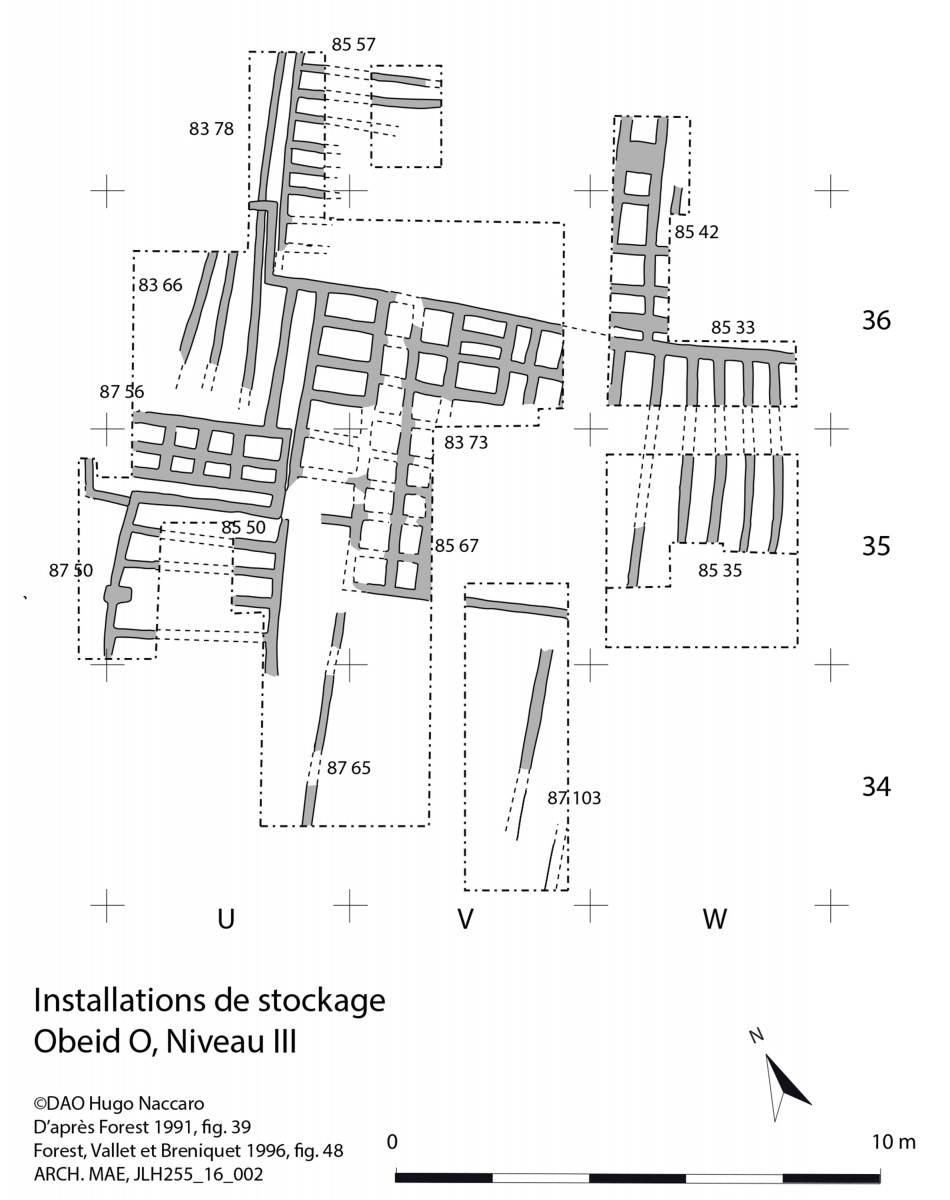

A second building rests on a grid of bricks, each empty square measuring 60 cm on each side. Above this brickwork sanitary grid are reed mats and above them the building itself. It is a cereals massive storage whose brickwork base protects the grains against moisture[2].

These large primitive silos (80 m2) raise a question about the origin of the first settlements. A standardised unit of measurement (60 cm), the use of moulded bricks, a functional structure carefully designed and built in the centre of the site: so many indications of a desire to rationalise collective housing through architectural plans. The specialisation of modular buildings centralises the management of the grain. From the end of the 7th millennium, communities of farmers gather around their collective granaries. They preserved barley and wheat, raised pigs and cattle, and were familiar with flax and date palm in the south. The movement is launched. Do they brew beer? Not yet, it seems.

Between 5900 and 5300, the dynamic goes up the Tigris and Euphrates rivers to the Anatolian border. The tell Kurdu excavated in the Amuq valley bears witness to this. Calculi, stamps, storage "labels" and various clay seals found in a central building suggest their administrative function and a collective management of food resources. The discovery of many carbonised grains points to the great extent of cereal cultivation. The first trials of irrigated agriculture have already been undertaken in Tell es-Sawwan and especially Tchoga Mami, in the foothills of Zagros (Iran). Wheat, 6-row barley, einkorn, common wheat and flax are the basic crops. Traces of canals 2 to 10 m wide surround this village. Irrigation increases yields. Some constructions of Tchoga Mami, with their grid foundation plans, are granaries, smaller than the houses. These grain storages are located at the centre of the village, a concrete symbol of community life. The large collective houses, too quickly interpreted as "temples", shelter and objectify a large part of social life.

These two evolutions, one technical (the granary), the other social (the collective house), are essential markers for the protohistory of beer brewing. Without the technical capacity to accumulate grain and overcome strict food survival, the beer brewing had no chance to emerge as a permanent activity. Without a new social organisation managing these starch surpluses, without the system of thought that invents and fixes social practices, drinking a fermented beverage would simply have no place among a farming community, even though the material means to brew it would be available. In the early agrarian communities, the constitution of grain stocks, their allocation to brewing instead of baking, the making of beer and its communal drinking, all these were subject to collective economic decisions, technical shared means, social mechanisms and consumption rituals. Nothing spontaneous or accidental. Never has a drop of beer been drunk without being socially "wrapped".

The Ancient Near East and the Ubaid period (6500-3750 BC)

The periods of Ubaid and Uruk , between the 6th millennium and the end of the 4th are decisive for the emergence of beer brewing in the Middle East. Major social developments pave the way for a general adoption of the fermented beverages. More complex organisations and new collective behaviours are superimposed on the experiences inherited from the small village entities of autarkic producers.

Enlarged communities gather around large collective houses with economic and religious vocations. These architectures and the technical means that accompany them, notably a large pottery, presuppose a management, if not centralised, at least collective management of grain stocks. At the same time, these enlarged social groups give rise to periodic or permanent gatherings of proto-urban communities. The emergence of beer seems to be linked in this region of the world to this double dynamic. The first one concentrates the collective winnowed grains in kinds of central granaries which make it possible to generate generate some starch surpluses. Without knowing who controls them, how and why in these remote times. The other dynamic creates a social need for religious ceremonies or collective celebrations during which food and fermented beverages are pooled and shared.

The oldest direct witness to the existence of beer represents two figurines around a vat. Engraved on a small stamp dated around -3800 found in Gawra (near Mosul, Northern Iraq), this scene of collective drinking already represents an advanced stage of integration of beer in social rituals[3].

This seal imprint is combined with other dance scenes, offerings and erotic postures that leave no doubt about the social and jubilant nature of the celebrations[4].

A few centuries later around 3100 BC, the first archaic tablets written on clay reflect the image of a beer brewing that had become a complete economic activity. The clues multiply: diversified raw materials (barley, emmer wheat, sweeteners based on honey or dates), sophisticated processes for preparing starch, advanced specialisation of tasks (maltsters, preparation of beer cakes and breads, baking bread and boiling wort, male and female brewers), specialised technical vocabulary, different kinds of beers and jars to brew them.

The presence of many sorts of beer at every levels of social, political and religious life seems to result from an acceleration in the history of the ancient Near East. What major developments precede and explain this maturity of beer brewing?

[1] Kujita & Finlaysonb 2008, Evidence for food storage and pre-domestication in Jordan Valley 11.000 BC - PNAS

[2] Forest J. D. 1996, OUEILI Travaux de 1987 à 1989 (Ed. Jean-Louis HUOT) ERC. Oueili et les Origines de l'architecture Ubaidienne. Et Eléments de chronologie sur le site Ubaidien d'Oueli.

[3] Rothman Mitchell S. 2002, Tepe Gawra : The Evolution of a Small, Prehistoric Center in Norhern Iraq, University of Pennsylvania, University Museum Monograph 112. Seal n° 1843 plate 49 and level XI/XA p. 37, relative chronology of Tepa Gawra Table 3.3 pp. 56-57, Increasing social complexity pp. 143-148.

[4] Tobler Arthur J. 1950, Excavations at Tepe Gawra vol. II, University of Pennsylvania Press, Philadelphia. Pp. 183-184, pl. CLXII dans l'ordre cachets n° 91, 82, 92 et 86.

en 5 rangées sur lesquelles reposait un plancher de roseau.jpg)