Beer versus dairy: complementarity farmers - pastoralists.

The Neolithic period implies the sedentarisation of only a part of the population: the farmers. The semi-nomadic pastoralists walk behind their herds and remain subject to the annual cycles of reproduction and grazing. What has been said of communities grouped together in villages around their starch stocks applies to the farmers. Their way of life (urbanisation, hierarchical society, food dependence on grain) called them to become brewers' peoples.

But this ecological and social specialisation does not imply that livestock breeders were expelled to the abandoned territories of the farmers or thrown back to the fringes of the cultivated-urbanised areas, in the night of history. These early pastoralists were not the nomads of the great steppes of Central Asia. They live in symbiosis with the farmers and, like them, frequent the urban world of the first cities. In most cases, depending on the ecosystems and human cultures in situ, herders and farmers led complementary, rather than autonomous or conflicting, lifestyles. To the first ones milk, cheese and meat, to the second beer, bread and porridge. Mesopotamian pastoralists and farmers constantly exchanged their products.

A very early Sumerian text (3th millennium BC) stages a banquet of the gods according to a standard topic of the Mesopotamian world:

« They drank sweet wine, they drank tasty beer, and when they had drunk sweet wine, and were filled with tasty beer, they began a quarrel in the middle of the flooded fields, they quarrelled in the Banqueting Hall. »

Dispute does not mean here a pitched battle, but a verbal jousting and contradictory debate on the true nature of things, the equilibrium of the world and the virtues of each person.

Cause of the Dispute : in ancient times, the Great Gods created two gods who teach men to cultivate plants and make herds growing in order to provide the Divine Banquet : Ashnan (litt. Grains) protectress of agriculture, and Lahar (litt. sheep) keeper of flocks. Indeed, what was there on earth before the cereals ?

« The people of those days,

did not know about eating bread.

They did not know about wearing clothes;

they went about with naked limbs in the Land.

Like sheep they ate grass with their mouths,

and drank water from the ditches.. » [1]

Who should have the pre-eminence, who should bend before the other: Ashnan the farmer or Lahar the shepherd? Each one defends his attributes before the divine assembly. Lahar claims wool, clothes, meat of the herds, pure milk, rare oils, skin and leather sandals, in short, the flagship products of the world of the semi-nomadic herders. Ashnan is proud of all cereal products, therefore beer. Here is one of her claims:

« When the BAPPIR has been carefully prepared in the oven,

and the TITAB tended in the oven,

Ninkasi [Mesoptamian goddess of beer] mixes them for me.

while your big billy-goats and rams

are despatched for my banquets.

On their thick legs they are made to stand separate from my produce.

Your shepherd on the high plain eyes my produce enviously.. » [2]

Here we are dealing with the brewing of beer. BAPPIR and TITAB are in the hands of Ninkasi, the Sumerian goddess of brewing, the ingredients of her craftsmanship. BAPPIR is a beer-bread composed of "raw grains + plants", certainly a bread made of cooked grains and amylolytic plants, lightly baked on the surface to be preserved. The TITAB is a beer-bread of same nature but made from malted grains. Ashnan thus claims, through her description of the fermented beverage served at the royal tables, the pride of place at their banquets! Beer, the grain beverage, must precede meat. Even the shepherd, from the depths of his steppe and his sheepfold, covets the pleasure and effects of beer.

The hinted images given by the Dispute express here the geopolitics of cereal growers with regard to pastoralists. Bread and beer, specialities of sedentary life, attract these wandering and bellicose groups, often ascetic by necessity. Emblems of the farming and urban cultures, bread and beer attract human flows to labour-hungry cities. Peacefully or brutally :

« When I come upon a captive youth and give him his destiny, he forgets his despondent heart and I release his fetters and shackles » utters Ashnan. Bread and beer relieve many pains !

But Ashnan adds : « When I am standing in stalks in the field, my farmer chases away your herdsman with his cudgel. »

Beyond the recurrent local conflicts raised by the courses and grazing of the herds of sheep and goats, one can guess some dialectic. If the overflowing silos of grains founded the political strength of the first city-states - bread and beer rations for soldiers and servile labour -, they ipso facto transformed these same cities and villages into prey for wandering bands from the farthest reaches of the steppes, deserts or mountains. Bands ready to plunder when the power of the cities weakens in the great plains. This balance induces, in times of peace, regular social exchanges between the world of farmer-irrigators and that of pastor-hunters. They take the form of "bread-beer" versus "meat-dairy" barter, based on sociability and exchanges between two complementary economic spheres. This is the deep political meaning of the Dispute of Ashnan and Lahar.

If Mesopotamian pastoralists and farmers contribute to the general prosperity, the policy of the city-states dictates that the breeders bend their knees before the cereal power of the cities. Ashnan is declared winner of the Dispute by the Great Gods of the Mesopotamian pantheon, Enki and Enlil. Other texts grant preeminence to the shepherds, notably in the cycle of the goddess Inanna and Dumuzi, guardian of the flocks.

This Dispute, exemplary for its antiquity and the explicit meaning of the text, has been replayed each time pastoralists and farmers have clashed in the past. Here are some historical cases:

- Occasional barter exchanges: grain/malt/beer for meat/fur/pellets. Examples :

- Case of the Mongols who know how to ferment mare's milk and produce an indigenous alcoholic drink (koumiss). However, they occasionally exchange with the farming and brewing peoples of the southern fringes of the Asian steppe. (Fermented beverages of central Asia peoples).

- Case of the Xiongnu pastoralists in northern China. Exchange of beer and malt with the court of the Great Empire of Han 202 BC-220 AD (China).

- Peul breeders from sub-Saharan regions in contact with farmers-brewers in the Niger Basin.

- Seasonal exchanges made permanent: grain for meat or horses. This economic complementarity enables semi-nomadic breeders to brew beer. Examples :

- Syria of the 2nd millennium: sheep breeders of the Djezire River <=> urban cultures of the Middle Euphrates.

- Southern border of Egypt during the Middle Kingdom and its relationship with Sudanese cultures.

- Nomads of the steppes of Central Asia (Kazakhstan) <=> farmers of the eastern and southern borders.

- Yak breeders from the Tibetan plateau <=> farmers-brewers from the Tibetan valleys (chang barley beer).

- Breeders of llamas from the Andean highlands <=> farmers of the low valleys (chicha corn beer).

- The balance of power: nomadic pastoralists become the predators of sedentary farmers-brewers when the latter's political and military power weakens or breaks down. Historical examples are numerous. Among the oldest, the peoples who came from the Zagros mountains or the Iranian highlands toppled the Mesopotamian dynasties (Sargon, Ur III). The peoples known as the Sea peoples swept over northern Egypt. In more recent times : Xiongnu (northern China), Huns (central Europe), Mongols (central Asia), Moghols (northern India), Aztecs (central Mexico), Fulani in the 18-19th centuries (Africa of the Niger basin).

The beer of the sedentary man, the milk of the semi-nomadic herdsman.

A common place turns semi-nomadic pastoralist peoples into exclusive drinkers of milk and water, or even of the blood of their cattle like the Mongols of Eastern Asia or the Maasai in the savannahs of East Africa. No alcoholic beverages among them, but the use of vegetable stimulants or psychotropic drugs. Were the semi-nomadic herders unaware of beer and how to make it with grains or starchy roots? Did the lack of starch stocks (grains, roots, tubers) resulting from their way of life deprive these peoples of the opportunity to drink beer?

Throughout their long history, most semi-nomadic pastoralists drank beer, brewing it after bartering grains from the farmers. For these pastoralists live in symbiosis with the farmers. This very general picture needs to be explained and nuanced according to continents, eras and cultures. The herdsman is not a wandering nomad. He periodically travels precise routes across the steppe or savanah. His existence is dominated by the annual cycle of his herds, which brings him back to his starting point. These vast loops put him in periodic contact with farmers to exchange meat, cheese, skins, sinew and horn for grain, beer, cloth, rope, pottery and sometimes fodder.

Is the herdsman a brewer? In general, no, except occasionally when he exchanges enough grain or when the economic or political complementarity with sedentary farmers becomes stronger.

A few examples :

- The "sons of the left" and "sons of the right" in the kingdom of Mari (Middle Euphrates of the second millennium BC) are sheep breeders. They consume beer on the occasion of large customary gatherings or military mobilisation. But the beer is brewed with the royal stock of grains. The brewers are Akkadians employed by the palace or local governors. These semi-nomadic sheperds drink beer but do not produce it.

- Mongols at the time of the great Khanats drink three kinds of fermented drinks. Rubrouck and the fountain of the 3 fermented beverages (koumiss - beer - wine)

- Fulani do not drink beer, except when they frequent urban communities. Nothing after their conversion to Islam except some slighted fermented porridge from sorghum or millet.

- The nomads of Northern China. The Han have a conflictual relationship with the Xiongnu of the North. Trade treaties with the Chinese imperial court stipulate provisions of beer and malt, especially during periods of relative peace to maintain it. (Brewery in the Han Empire).

- Herders on the Tibetan highlands traded horses and hides for grain during the Chinese Jin, Sui, Tang and Song dynasties.

- The remaining settled farming peoples of the Caucasus are in contact in the north with the vast Eurasian steppes stretching from the Ukraine to the Altai. They have been inhabited by pastoralists since the Scythians from the Andronovo culture have given up farming in favour of pastoral nomadism in the 8th century BC. The Ossetians, heirs from the Alain people, bear witness to these oscillations between the nomadic life of the pastoralists and the sedentary life of the beer-drinking farmers.

Economic and technical exchanges between pastoralists and farmers are numerous. They have partly influenced the beer brewing throughout history. The traditional beverages of the pastoralists are fermented milks (of the koumiss type made by the Turco-Mongols). They are related to the world of lactic fermentations. The massive use of lactic ferments has made the beers of the farmers living on the margins of these steppe worlds evolve towards acidulous forms. There is a very thin boundary between a beer brewed by the method of acid hydrolysis and a decoction of barely fermented grains, assimilated to food. These historical regions of intense exchange between pastoral and cereal growing cultures have so far been neglected by the history of beer.

Beer and water pollution by humans and animals.

According to the Mesopotamians, before agriculture humans "like sheep they ate the grass with their mouths, drinking the water from the ditches."

Once the granaries were full, they could brew beer and leave the stagnant water behind. All right. But with the grains came the herds, the domestic animals and the stables. The cohabitation of people and animals polluted the water. Worse, the building of the first cities confined their inhabitants so close to the polluted waters. In urban areas, the concentration of humans and animals led to the pollution and accumulation of contaminated water. The same Mesopotamians, who sang the praises of urban life, also sometimes praised nomadic life in the middle of the steppe, on the fringes of deserts or in the mountains. There life is healthy, soil is not contaminated, water in the wineskins is pure.

The first great cities of Eastern antiquity (Uruk, Habuba-Kabira, Eridu, Ur) or Indian antiquity (Harrapa, Mohenjo-Daro) have terracotta drainage facilities and gutters. The issue of wastewater is crucial in the world's first major urban complexes, all of which are built and grow along waterways. In warm climates, waste decomposition was incompatible with human concentration. The issue is directly relevant to brewing. Water is one of the 3 technical axes for brewing beer. Where was the water taken from to brew beer?

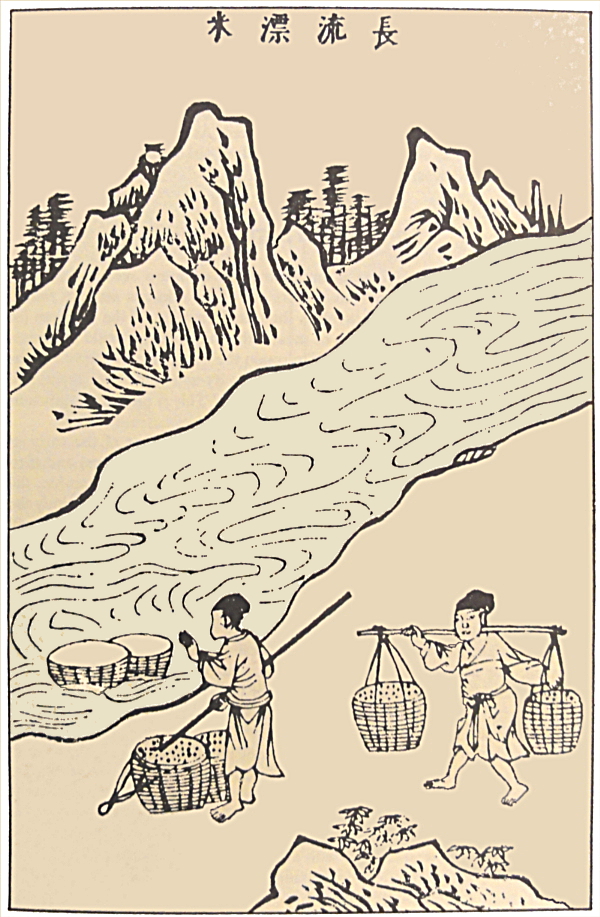

One Chinese iconography from the 17th century (1637) shows a brewer washing fermented rice in the water of a pure mountain river. It is taken from a book that explains the making of red rice, a rice fermented with Rhizopus monascus whose mycelium gives the grain a purple colour. This rice is used to brew a highly prized beer. So much for rural brewing[3].

But where was the water drawn from in the heart of the cities or on their outskirts to make beer?

Firstly, the technical aspect. Acidification of the wort (pH < 5-6) eliminates certain pathogens but favours bacteria (see Fundamentals). Alcoholic fermentation partially eliminates viruses and bacteria. But the low alcohol content (3-4% vol.) of ancient beers (to be proven anyway) offered little protection. Is beer an answer to a health problem of the first urbanised cultures, as has often been written? No, beer existed and brewing developed long before the building of the great ancient cities at the beginning of the 3rd millennium in the Near East, Egypt and Asia.

The economic aspect. If urban water pollution prevented brewing in the heart of cities, the first breweries were established on the outskirts of cities, never in their centres. Near waterways (river, canal) and ports. Except when brewing beers for the gods (offerings) or the palace (royal entourage), beverages that had to remain "pure". The concern for the purity of offerings, especially beer and bread, required that a brewery be set up within the sanctuaries themselves, which were built in the centre of the cities. This avoided any risk of magical contamination between the time of the brewing process and that of consecration of the various beers. The brewing workshops are consequently dedicated to the beers of the offerings. They are located in the sanctuaries, not on the outskirts of the cities.

Finally, the religious aspect. The remains of breweries from the 3rd and 2nd millennia discovered in Iraq all correspond to brewing installations attached to temples or sanctuaries (list). Only one, more recent, corresponds to a "commercial" brewery (on the Middle Euphrates). Religious complexes were generally located in the heart of cities and were considered to be the abode of their patron gods. Food offerings had to be prepared, at least at the time we are talking about, in the protected and pure enclosure of the sanctuary. The beer and bread, symbolically consumed by the deities, were then redistributed among the clergy.

At this time, the palaces merged their political power with that of the gods. The city appoints a king-priest as its head. The brewery (or breweries) serving the palace had to follow the organisation of the temple brewery: isolated from the city within the palatial architectural complex, supplied by the palace granaries, supplied with water from springs or reserved wells, operated by a workforce chosen from among the servants of the palace or the clergy. This type of brewery operates in a closed circuit to manage the entire brewing process, from the supply of ingredients to the delivery of special beers.

[1] Alster, Vanstisphout 1987, 1-43. English translation http://etcsl.orinst.ox.ac.uk/cgi-bin/etcsl.cgi?text=t.5.3.2# §12-25

[2] http://etcsl.orinst.ox.ac.uk/cgi-bin/etcsl.cgi?text=t.5.3.2# §116-122

[3] Sung Ying-Hsing, T'ien-Kunk K'ai-Wu, 1637. Translated by E-Tu Zen Sun and Shiou-chuan Sun, subtitle Chinese Technology in the Seventh Century. Dover publications 1966. Illustration p. 291.