Beer management in the Paleo-Babylonian kingdoms (ancient Syria).

The central role of brewing in Eastern societies is attested since the 4th millennium, from Susiana (former Iran) to the Mediterranean, from Anatolia to the Persian Gulf. Beer is a daily beverage, a ceremonial and cult beverage, the substance of offerings to the dozens of deities of the Mesopotamian pantheons. Beer and bread are distributed in the form of rations to soldiers, farm workers and palace staff.

It is so deeply rooted in the Mesopotamian material and mental universe that it inspires a wide variety of beliefs and rites among all social categories, from the most modest labourer to the king, his generals and priests. This omnipresence of beer has engendered thousands of cuneiform tablets, stamps, inscribed stones, pictorial seals, brewing pottery, cups and drinking straws.

The economic and social function of beer persists in the second millennium. It is even strengthened in the North, today's Syria. The Syrian palaces archives testify to this. As in the previous millennium, we know this thanks to detailed accountings of what enters and is consumed in the palaces and in the sanctuaries as well, and of what they supply. This vision of what really happened, without literary obscuration, takes us to the heart of the real daily material life of the inhabitants. Here beer is omnipresent.

Another feature of the North Mesopotamian archives is the preservation of letters, memos and diplomatic correspondence. Some of these archives condense events that occurred over a very short period of time, one or more years, in the heart of the political power centres of the time. They recount the thread of events almost on a daily basis and provide unprecedented details on social logic, ways of living and thinking that are never found in the arid and concise bookkeeping tablets. These diplomatic archives contain many details about beer, drinking manners, brewing techniques and the social functions of this fermented beverage.

The geography of fermented beverages in Syria in the second millennium is often caricatured. The Mesopotamian South would be devoted to beer and the Syrian North to wine (Syria, Lebanon, Levantine city-states). Beer is in fact dominant everywhere. Wine is only the beverage of a restricted elite which makes it the object of a trade and a luxury marker of its social status.

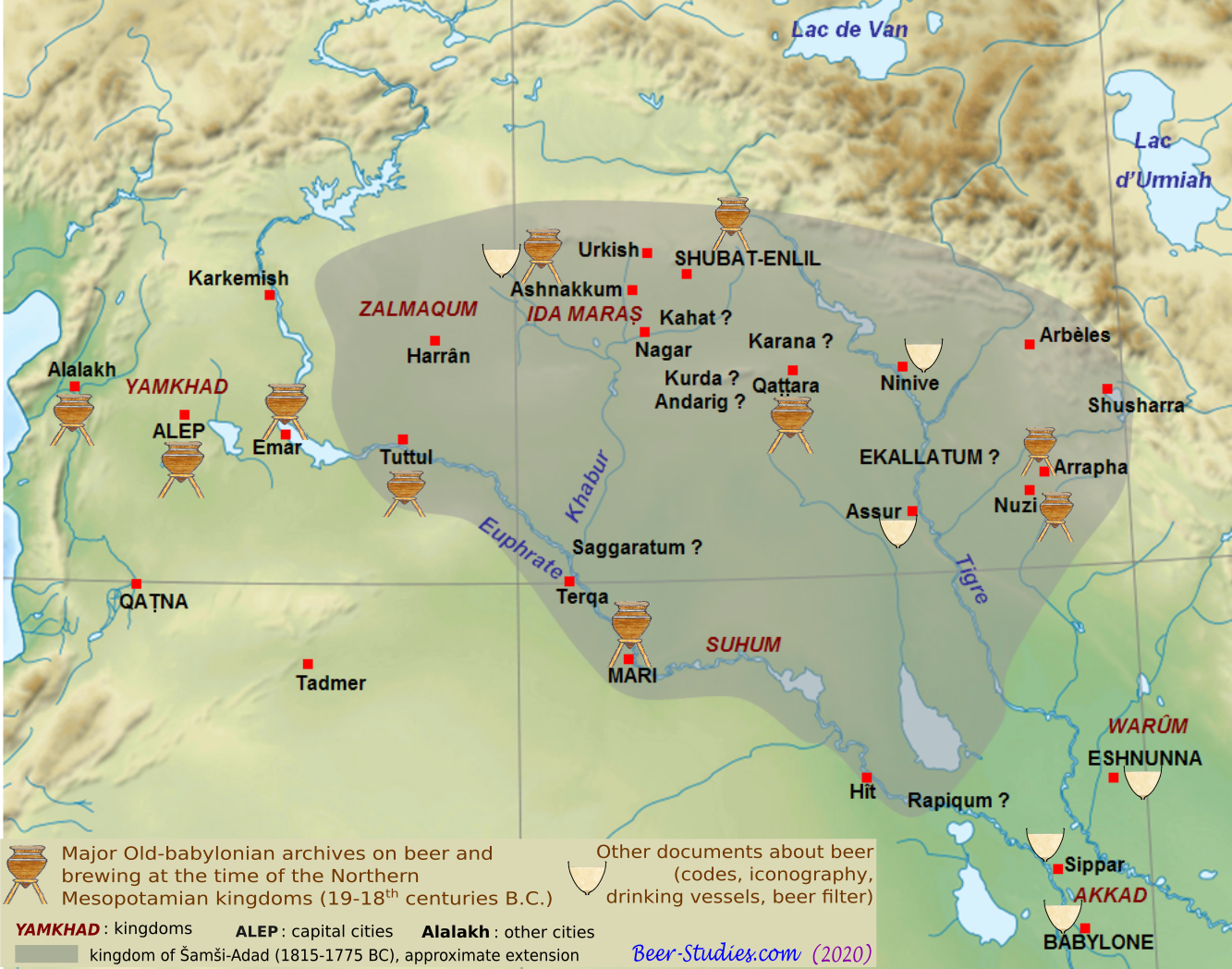

In the second millennium, Akkadian culture is strong in Syria. Akkadian is used as a common or diplomatic language and as a written language. The lingua akkadica of this time is used throughout Mesopotamia, from the Persian Gulf to the high valleys of the Tigris and Euphrates rivers. Writing, accounting systems, cuneiform tablets, document archiving, all these sophisticated technologies have borrowed to the great Akkadian culture and progressed on its very ancient foundations. This is why archaeologists have found some important palatial archives dated from the 18th and 17th centuries. These are distributed throughout the region (see map), from the Mediterranean Sea in the west to the banks of the Tigris in the east. These palaces and the cities that supported their political authority belong to ancient Syrian kingdoms :

- Alalah and Emar, cities from the westerner Syria

- Shubat-Enlil, Chagar Bazar, Tell Brak and Qattarâ in the Khabur triangle(north of Euphrate)

- Mari–Tell Biya on the Middle-Euphrate river

- Gasur (21th century) and Nuzi (16-15th centuries) on the eastern fringe of the Mesopotamian Plain

As part of the Fertile Crescent, Syria is a very ancient cereal-growing region. Annual rainfall exceeds 250 mm, the drought threshold. Irrigation of the fields is not essential. Except in the Khabur basin, partially irrigated in the second millennium, dry agriculture is practised everywhere with only one harvest per year. Where barley and wheat abound, brewing flourishes.

Syrian physical geography is over-determined by very old political and urban structures (see Habuba Kabira). The societies emerging in Syria around 2500 BC (Ebla, Mari, ...) are complex and hierarchical. The minorities ruling these small kingdoms retain their power thanks to their economic wealth. The concentration of grain surplus (silos of sanctuaries and palaces), the mobilisation of a rented, servile or dependent labour force, the control of land, long distance exchanges (wood, stones and metals) give cereals and their derivatives a strategic role. Beer is one of the cereal products whose importance is growing in the economic and social management of these kingdoms. Beer is at the heart of an elaborate system of rations in kind distributed to the people serving the new palace powers.

The Syrian archives design a brewery dependent on the local economy. Here, a manager-brewer coordinates the tasks and management of the grains (harvesting, threshing floors, storage, malting). There, brewers provide the king's table. Elsewhere, brewers are active around the palace and in the villages. The military campaigns are not without mobilising brewers who prepare beer for the soldiers who are peasants or dependents mobilised during the agricultural off-season. The distribution of beer respects the social pyramid. The great protective gods receive their share.

All this could be said and shown about the kingdoms of southern Mesopotamia. Syria, on the other hand, offers an original population settlement. Between the Euphrates, the Tigris and the Anatolian foothills the shepherd-breeders are nomadising . They are in close seasonal contact with the cereal farmers of the fertile valleys (Euphrates, Balih, Habur, Tigris, Little and Big Zab, Diyala).

Some invaluable documents from this period open a window on the episodic meetings between farmer-brewers and shepherd-cheesemakers. Beer is not absent from their exchanges and even plays a central role in social mediations, oaths, collective commitments, weddings, customs and festivities. These two communities maintain a close economic dependency that is reinforced by inter-ethnic exchanges.