Andean cultures, Inca empire, Chile

- Aaronson Wendy,Ridgely Bill 1994, Adventures inChicha and Chang: Indigenous Beers of the East and West, Zymurgy 17(1), 32:37.

- A very short article on the modern brewing of corn chicha and Tibetan barley chang.

- Bejarano Jorge1950, Laderrota de un vicio: Origen e historia de la chicha, EditorialIqueima, Bogotá.

- Berryman Carrie Anne 2010, Food,Feasts, and the Construction of Identity and Power in Ancient Tiwanaku: ABioarchaeological Perspective. PhD. Vanderbilt University, Tennessee.

- Brass Tom 1989, Beer DrinkingGroups in a Peruvian Agrarian Cooperative, Bulletinof Latin American Research 8(2), 235:256.

- Bray Tamara L. 2003a, To DineSpendidly: Imperial Pottery, Commensal Politics and the Inca State. InThe Archaeology and Politics of Food and Feasting in Early States andEmpires, ed. Tamara L. Bray, 93-142 New-York.

- Bray Tamara L. 2003b, The Commensal Politics of EarlyStates and Empires, In The Archaeology and Politics of Food and Feastingin Early States and Empires (Tamara L. Bray ed), New York, 1:13.

- Bray Tamara L. 2003c, Inka Pottery asCulinary Equipment: Food, Feasting, and Gender in Imperial Design, LatinAmerican Antiquity 14(1), 3:28.

- Burger Richard L., Van Der Merwe NikolaasJ. 1990, Maize and the Origin of Highland Chavín Civilization: An IsotopicPerspective, American Anthropologist 92(1), 85:95.

- Corn is a type C4 (metabolism) cereal, as opposed to type C3 plants (quinoa, potato). The C4 plants leave an isotopic signature in the bones which makes it possible to evaluate the contribution of corn in human food. Chavin's skeletons (850-200 BC) have a C4 rate lower than expected. This implies that corn does not have a predominant role, although it has been domesticated for a long time. This observation has already been made for the Andean pre-ceramic periods (c. 2000 BC).

- Burland C. A. 1951, Chibcha Aesthetics,American Antiquity 17(2), 145:147.

- The Chibcha people (Muiscas) lived in Colombia, in the region of Bogota. Great lovers of corn beer and skilled metallurgists, they have created drinking cups and vases of great refinement.

- Butler Barbara 2006, Holy Intoxication toDrunken Dissipation: Alcohol among Quichua Speakers in Otavalo, Ecuador.University of New Mexico Press, Albuquerque.

- Camino Lupe 1987, Chicha de maíz: Bebiday vida del pueblo Catacaos, Centro de Investigación y Promoción delCampesinado–Piura.

- Cavero Carrasco Ranulfo 1986, Maíz,chicha y religiosidad andina, Universidad Nacional de San Cristóbal deHuamanga, Ayacucho.

- Cadwallader Lauren, Beresford-Jones DavidG., Whaley Oliver Q., O’Connell Tamsin C. 2012, The Signs of Maize? AReconsideration of What d13CValues Say about Palaeodiet in the Andean Region, Human Ecology 40,487:509.

- The authors note that other type C4 food plants were consumed in the Andes during the pre-Columbian era, by the men and animals they eat. This should lead to revise the conclusions on the low level of C4 for the pre-ceramic periods of the Andes (Burger 1990).

- Cook Anita, Glowacki Mary 2003. Pots, Politics and Power: HuariCeramic Assemblages and Imperial Administration. In The Archaeology andPolitics of Food and Feasting in Early States and Empires, ed. Tamara L.Bray, 173-202. New-York.

- Cummins Thomas B. F. 2002, Toasts withthe Inca: Andean Abstraction and Colonial Images on Quero Vessels. University of Michigan Press, AnnArbor.

- Queros are traditional terracotta bowls from the Andes, imagined and intended for drinking corn beer. Their decorating scenes tell of the influence of the Spanish colonization on their own representations and the mental universe of the Amerindians after the conquest.

- Cutler Hugh, Cardenas Martin 1947, Chicha, A Native South AmericanBeer, Harvard University Botanical Museam Leaflets 13(3).

- D'Altroy Terence N., Hastorf Christine A.1984, The Distribution and Contents of Inca State Storehouses in the XauxaRegion of Peru, American Antiquity 49( 2), 334:-349.

- In the Inca Empire, the region of Xauxa (central highlands) included more than 2,000 warehouses distributed in 52 architectural complexes. Their spatial organization and architectural standardization suggest that these storage means were controlled by the imperial authority. Excavations from 6 warehouses found the remains of plants (corn, quinoa, potato, lupine) and fragments of Inca storage containers. Part of these starchy stocks were converted into beer.

- D'Altroy Terence, Earle Timothy, BrowmanDavid, La Lone Darrell, Moseley Michael, Murra John V., Myers Thomas,Salomon Frank, Schreiber Katharina, Topic John 1984, Staple Finance,Wealth Finance, and Storage in the Inka Political Economy, CurrentAnthropology 26(2), 187:206.

- The Inca empire collects, stores and redistributes a huge volume of products and prestige goods. These mechanisms have reinforced the economic and political power of the Incas. The aqllakuna (selected women) make textiles and brew beer.

- Doughty Paul L. 1971, The Social Uses ofAlcoholic Beverages in a Peruvian Community, Human Organization 30(2),187:197.

- Duncan Neil A, Pearsall Deborah M.,Benfer Robert A. 2009, Gourd and squash artifacts yield starch grains offeasting foods from preceramic Peru, PNAS 106(32), 13202:13206.

- http://www.pnas.org/content/106/32/13202.full

- Remains of gourds and squash discovered on the archaeological site of Buena Vista (central Peru, around 2200 BC). They contained traces of cassava starch (Manihot esculenta), potato (Solanum sp.), And chilli seeds (Capsicum spp.), Arrowroot (Maranta arundinacea) and algarrobe (Prosopis sp .). Feastings were organized on the site. These are the oldest testimonies of consumption of Algarrobe and Amarante in Peru. In addition, the containers provide evidence that cassava and algarrobe, which can be fermented, may have been the ancient production base for beers of various kinds.

- Gero Joan 1990, Pottery, Power, and ...Parties!, Archaeology 43(2), 52:56.

- Gero Joan 1992, Feasts and Females:Gender Ideology and Political Meals in the Andes, Norwegian ArchaeologicalReview 25, 15:30.

- Goldstein, Paul S. 2003, From Strew-Eaters to Maiza-Drinkers: TheChicha Economy and the Tiwanaku Expansion. In The Archaeology and Politicsof Food and Feasting in Early States and Empires, ed. Tamara L. Bray,143-172. New-York.

- Goldstein David John, Coleman RobinChristine 2004, Schinus Molle L. (Anacardiaceae) Chicha Production in theCentral Andes, Economic Botany 58(4), 523:529.

- Goldstein Paul 2003, From Stew-Eaters toMaize-Drinkers: The Chicha Economy and the Tiwanaku Expansion. In TheArchaeology and Politics of Food and Feasting in Early States and Empires(Tamara L. Bray ed.), New York, Kluwer Academia/Plenum, 143:172.

- Gómez Huamán, Nilo 1966, Importancia social de la chicha comobebida popular en Huamanga, Wamani 1(1), 33:57.

- Gose Peter 2000, The State as a Chosen Women: Brideservice and theFeeding of Tributaries in the Inka Empire, American Anthropologist 102(1),84:97.

- The duty of the Inca palaces to provide beer, food and clothing to the tributaries of the empire, in apparent opposition to the policy of warlike and predatory submission of the same empire.

- Hames Gina 2003, Maize-Beer, Gossip, andSlander Female Tavern Proprietors and Urban, Ethnic Cultural Elaborationin Bolivia, 1870-1930, Journal of Social History 37(2), 351:364.

- The story of a young Bolivian girl, Manuela Serrano, who left in 1887 from Padilla, her native village, to emigrate to Sucre, the capital. There, after a few years of savings and new social ties, she became chichera (brewer) and created her own chicheria (brewery / sale of beer). But it must also build a new identity. She became a chola, an urban Native American living on the outskirts of the big Colombian cities. In 1910, she succeeded in creating a chicheria for her daughter Maria, another one for her son Pastor.

- Hartman Günther 1958, AlkoholischeGetränke bei den Naturvölkern Südamerikas, Berlin.

- Hastorf Christine, Johannessen Sissell1993, Pre-Hispanic political change and the role of maize in the centralAndes of Peru, AmericanAnthropologist 95(1): 115-138.

- The stocks of corn kept from post to post along the Andes route are a means of consolidating the political power of the Incas of Cuzco in their vast empire. These posts supply the imperial messengers. On the spot, the corn is converted for them into pancakes and beer. These corn reserves are the responsibility of the local populations.

- Hayashida Frances M. 2008, Ancient beerand modern brewers: Ethnoarchaeological observations of chicha productionin two regions of the North Coast of Peru, Journal of AnthropologicalArchaeology 27, 161:174.

- An observation of the current methods of brewing the chicha beer reveals changes which must made scholars cautious when they are used to describe old procedures. Even the traditional brewery of Native American corn beers is evolving.

- Henderson Hope, Ostler Nicholas 2005, Muisca settlementorganization and chiefly authority at Suta, Journal of AnthropologicalArchaeology 24, 148:178.

- The first signs of inequality and formation of chiefdoms date from the primitive Muisca period, early 11th century in Colombia. Political competition is increasing between heads of small establishments. Archaeologists interpret the appearance of cups and jars decorated to drink corn beer during collective celebrations as one of the telltale signs of this march towards more complex social organizations.

- Jennings Justin 2005, La Chichera y El Patrón: Chicha and theEnergetics of Feasting in the Prehistoric Andes, American AnthropologicalAssociation 14, 241:259.

- http://www.rom.on.ca/sites/default/files/imce/beerap3a.pdf

- Jennings analyzes the cost of brewing the chicha beer, the resources and the skills required. The family sponsoring a celebration or agricultural work by massive distributions of shisha must have economic means (fields, pottery, brewing equipment, firewood, labor, time) above the average. Hookah parties are a real social investment.

- Jennings Justin, Antrobus KathleenL., Atencio Sam J., Glavich Erin, Johnson Rebecca, Loffler German, LuuChristine 2005, "Drinking Beer in a Blissful Mood", CurrentAnthropology 46(2), 275:303.

- http://www.rom.on.ca/sites/default/files/imce/beerca.pdf

- Jennings and her co-authors explore the economic and technical means of mass brewing corn beer as part of the festivities organized in pre-Columbian Peru. Besides their social and political ramifications, these festivals involved an important organization of the brewery to supply the festivals with fermented drink. Complete by widening Jennings 2005.

- Jennings Justin, Chatfield Melissa 2009, Pots, Brewers, and Hosts:Women´s Power and the Limits of Central Andean Feasting. In Drink,Power, and Society in the Andes, (ed) Justin Jennings and Brenda Bowser,University Press of Florida, Gainesville, 200:231.

- Heath Dwight 1962, Drinking Patterns ofthe Bolivian Camba. In Society, Culture, and Drinking Patterns (DavidPittman & Charles Snyder, eds.) New York, 22:36.

- Holmberg Alan 1971, The Rhythm ofDrinking in a Peruvian Coastal Mestizo Community, Human Organization30(2), 198:202.

- La Barre Weston 2009, Native American Beers, American Anthropologist 40(2), 224:234.

- Inventory of beers brewed by the Amerindian peoples of South and Central America.

- LlanoRestrepo, María and Marcela Campuzano Cifuentes Marcela 1994, La chicha, una bebida fermentada a través de la historia. InstitutoColombiano de Antropología, Bogotá.

- History of corn beers, cassava from the pre-Columbian Muiscas until 1940. This history is part of the politics of Colombia, its legislation, its urban expansion and its mixed and indigenous cultures.

- Lomnitz Larissa 1969, Patterns of AlcoholConsumption among the Mapuche, Human Organization 28(4), 287:296.

- The Mapuche live in southern Chile. Their old traditional potato or corn beers have been replaced by industrial beers, cider, wine or distilled alcohol. The Lomnitz survey focused on a group of new Mapuche immigrants to Santiago. Little historical information.

- Mangan Jane Erin 1999, Enterprise in the shadow of Silver :colonial, andeans and the culture of trade in Potosi, 1570-1700. PhDDepartment of History of Duke University.

- Chicha, chicherias and chicheras in the new colonial city of Potosi.

- Meyerson, Julia 1990, ‘Tambo’: Life in anAndean Village. University of Texas Press, Austin.

- Moore Jerry 1989, Pre-Hispanic Beer in CoastalPeru: Technology and Social Context of Prehistoric Production, AmericanAnthropologist 91 (3) :682-695.

- Moore shows that there are several modes of production of corn beer within the empire of the Incas, therefore several kinds of brewery. One at the service of imperial power within the walls of its palaces, another at the service of the empire across its vast territory, a last for the festivals and celebrations in which the people participate. This table re-establishes the complex situation of the brewery within a very organized and structured empire.

- Morales Mónica P. 2012, ReadingInebriation in Early Colonial Peru. New Hispanisms Cultural & Literary Studies, AshgatePublishing Company, USA.

- Especially the strategy of Catholic missions in Peru to outlaw collective drink customs whose deep cultural reasons were not understood.

- Morris Craig 1979, Maize Beer in the Economics, Politics, andReligion of the Inca Empire. In Fermented Food Beverages in Nutrition, ed.Clifford F. Gastineau, William J. Darby, Thomas B. Turner, 21-34. AcademicPress.

- A pioneering article on the central role of corn beer in the construction of the Inca empire, before it became an ordinary and indigenous drink with the Spanish conquest.

- Moseley Michael E., Nash Donna J., Ryan PatrickWilliams, deFrance Susan D., Miranda Anna, Ruales Mario 2005, Burning Downthe Brewery: Establishing and Evacuating an Ancient Imperial Colony atCerro Baúl, Peru. Proceedingsof the National Academy of Sciences 102(48), 17264:17271.

- The remains of a brewery on the borders of the ancient Wari empire in the north and Tiwanaku in the south, dated between 600 and 1000. These are to date the oldest archaeological traces of brewing on the American continent.

- Muelle Jorge 1978, La chicha en el distrito de San Sebastián, InTecnología Andina, Ravines (ed.), Inituto de Estudios Peruanos, Lima.

- Nicholson G. Edward 1960, Chicha maizetypes and chicha manufacture in Peru, Economic Botany 14(4), 290:299.

- The inventory of the types of chicha-beer and the description of their brewing methods (insalivation, malting, acid hydrolysis, amylolytic ferment).

- Orlove, Benjamin, Ella Schmidt 1995,Swallowing Their Pride: Indigenous and Industrial Beer in Peru and Bolivia,Theory and Society 24, 271:298

- Randall Robert 1993, Los dos Vasos. Cosmovisión y politica de laembriaguez desde el inkanato hasta la colonia, In Borrachera y Memoria,experiencia de lo sagrado en los Andes, Thierry Saignes (compilador),hisbol / IFEA Lima Perú, 73:111.

- Andean beer was involved in the circulation of liquids within pre-Columbian Amerindian societies.

- Ridgely Bill 1994, Gold of the Aqllakuna, online http://xb-70.com/beer/chicha/aqllakun.htm (access may 2013).

- A page on the Inca corn beer, its production by the "chosen women" (Aqllakuna) for the Inca court.

- Ryden Stig 1930, Une tête-trophée de Nasca, Journal de la Sociétédes Américanistes 22(2), 365:371.

- A Nasca trophy skull for drinking corn beer, with its reproduction. Kept in the Göteborg museum.

- Saignes Thierry 1992, Boire dans lesAndes, Cahiers de sociologie économique et culturelle 18, Lille, 53:62.

- This article questions the role of drunkenness in Andean culture before and after the Spanish conquest. Corn beer is drunk by the Amerindians beyond the simple physiological need. It serves as a vector to stimulate sociability and communicate with the invisible.

- Saignes Thierry 1993, Borracherasandinas. ¿Por que los indios ebrios hablan en espanol?, in Borrachera yMemoria, experiencia de lo sagrado en los Andes, Thierry Saignes(compilador), hisbol / IFEA Lima Perú, 43:71.

- What the Indians of the Andes conquered by the Spanish were looking for with the maize beer?

- Salazar-Soler Carmen 1993,Embriaguez y visiones en los Andes. Los Jesuitas y las"borracheras" indigenas en el Perú (Siglo XVI y XVII), inBorrachera y Memoria, experiencia de lo sagrado en los Andes, ThierrySaignes (compilador), hisbol / IFEA Lima Perú, 23:42.

- The Amerindian feasting and drunkenness misunderstood and fought by Jesuits.

- Uzendoski Michael A. 2004, Manioc Beerand Meat: Value, Reproduction and Cosmic Substance among the Napo Runa ofthe Ecuadorian Amazon, The Journal of the Royal Anthropological Institute10(4), 883:902.

- This very dense article wrtitten by an ethnologist poses the central problem which animates the whole general history of beer. Beer is not just a drinkable matter that is both nourishing, refreshing and intoxicating. Beer has created social linkages within a community ( lubricating celebrations, sharing between groups) and symbolic values (cosmology, magic of fermentation, division of genders, contact between the living and the deceased).

- Valdez Lidio 2006, Maize Beer Productionin Middle Horizon Peru, Journal of Anthropological Research 62, 53:80.

- Vázquez Mario 1967, La chicha en lospaíses andinos, América indigena 27, 264:282.

- Wagner Catherine Allen 1978, Coca, Chicha, and Trago: private andcommunal rituals in Quechua community. PhD University of Illinoisat Urbana-Champaign.

- Central role played by the maize beer in collective or private celebrations of a community of Songo, High-Plateaux of southern Peruvian, in connection with the cultivation of coca and wheat.

- Weismantel Mary J. 1991, Maize Beer andAndean Social Transformations: Drunken Indians, Bread Babies and ChosenWomen, Modern Language Notes 106(4), 861:879.

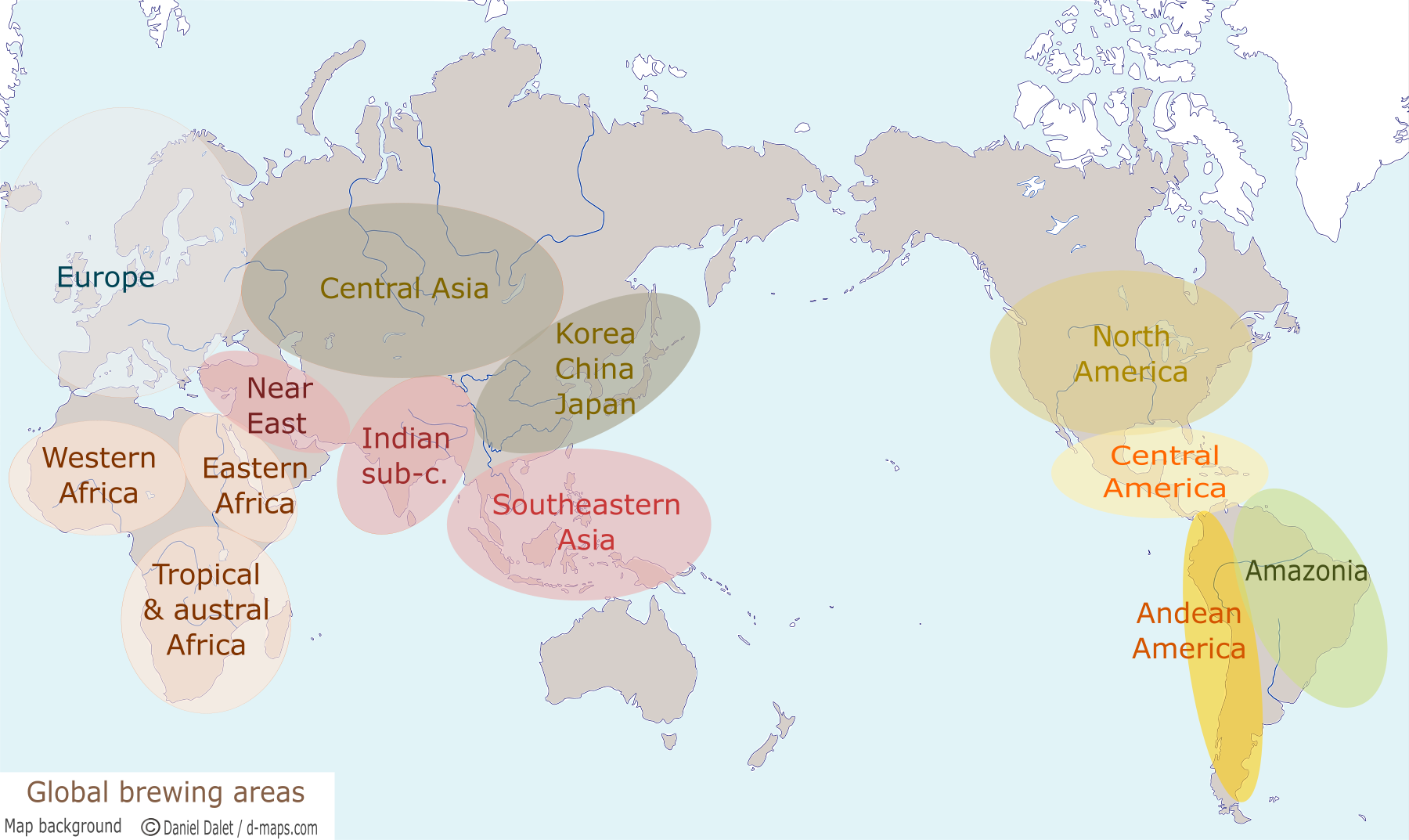

Click an area for other regional bibliographies.