First agrarian communities, first floods of beer !

Plants rich in starch are very energetic. Starch, which is easy to store in a dry state and to rehydrate, is easily transformed into solid food (bread, semolina, groat, cake), liquid food (soup, gruel, porridge, decoction) or a fermented drink (beer), depending on the needs. These three variants of "starch cooking" have had close technological links between them since their origin.

A large part of mankind owes its demographic growth and social evolution to it. In order to benefit from the advantages of starch, depending on the region of the world, farmers societies have grown cereals, horticulters societies have planted tubers (manioc, yam, potato, taro, ...), hunters-gatherers communities have collected starchy fruits or seeds (plantain, carob tree, ...) and other starchy plants (sago, chestnut, ...).

According to archaeology (Archaic beers), the regular production of beer only appears several millennia after the mastery of the agricultural activities, a time lag that we must understand. This discrepancy, known for cereal growing societies, remains difficult to evaluate for the first horticultural societies in tropical regions, due to the lack of sufficiently early archaeological evidence.

Why don't the first farmers/horticulturists brew beer as soon as they have a reliable, regular and plentiful supply of starch? Why do we have to wait in the Near East for about 5000 BC whereas the main cereals are already cultivated around 10,000 BC?

The solution to this enigma does not lie in technology. The first farmers mastered all the necessary techniques: grain storage, pottery, basketry, firing. They could theoretically brew and drink as much beer as they had available starch. The reasons for this chronological gap are social. Beer quenches thirst and intoxicates, of course. But to fulfil these two immediate functions beer must comply with the cultural rules for the circulation of commodities allowed by the social group. These rules include food and beverages which are strong symbolic media, sources of social bonds but also of conflicts and power issues.

Beer production involves the collective management of starch reserves (a political terrain), the work to convert them into fermented beverages (a technical field), as well as the reproduction of each person's economic roles and functions (a social organisation field). The flows of beer within a social group follow the social rules: drinking manners, respect for ranks and social hierarchies, gender, age groups, etc. They cannot endanger a social organisation, but on the contrary reinforce it, year after year, day after day.

Ten millennia ago, social rules organized the first Neolithic communities in the Near East or China, later in Africa, Europe or America. Did they favor or hinder the emergence of the beer brewing? Understanding the proto-history of brewing affects the way it is studied in antiquity and in more recent periods.

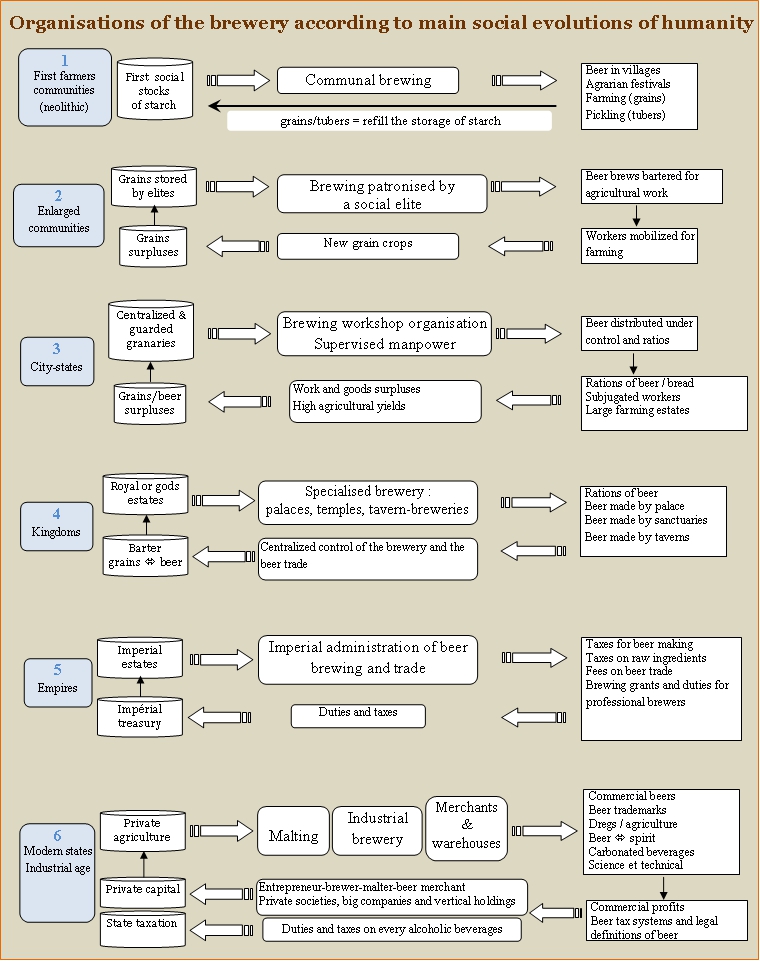

In an attempt to respond, we propose a general framework that divides the evolution of human societies into three major socio-economic stages. Each of these allows us to study the brewing of beer in its relationship with social structures, economic organization and technological development. This overall evolutionary scheme remains theoretical and open to criticism. But it allows a confrontation - which would like to be a verification - with the available documents and archaeological data. This will be the object of the three following parts below:

- The primitive agrarian communities and the emergence of beer brewing.

- The city-states and the first kingdoms on the planet.

- The imperial organisations and the role of the Brewery.

Main steps in the evolution of the beer brewing since its origin.

The idea of an epigenesis of brewing underlies this general historical picture. Each evolution of the brewery brings its own level of complexity in the technical, economic and social fields. Each stage is based upon the previous level and integrates its achievements.

The history of the brewery offers many examples of such overlapping organisations. Their details vary according to epochs, continents and cultures. The Paleo-babylonian Mesopotamia (2rd millennium BC), the Maurya India (4th century BC) or the Han China (206 BC to 220 AD) offer examples of imperial brewery organisation (level 5 in diagram) which add to older methods of beer production (domestic brewing, beer brewing by urban workshop, tavern-brewery).

Central Europe in the 18th and 19th centuries (Austro-Hungarian Empire, Bavaria, Prussia, Poland, etc.) presents another exemplary case, as it includes the very recent industrial organisation of brewing. In this historical example, the beer brewing is located at all the 6 levels which overlap in the overall economic organisation of those empires or empires-like :

- Collective brewing in village festivals + domestic beer brewing. The beer is brewed with the grain stocks of each household on the occasion of an agricultural or religious festival. About a hundred participants and a few hundred liters of beer are brewed using local processes. The domestic brewing is done all year round according to the grain stocks of the household. The beer is intended for members of the more or less extended family. This is the most archaic level. (diagram: level 1)

- Brewery of agricultural estates sponsored by large landowners for the use of workers and labourers on their agricultural estates. The beer is not marketed. It is bartered for work. Beer is seasonal like agricultural work. The brews are regular: about a hundred liters of beer are drunk every day and brewed according to a recipe specific to each farmstead. (diagram: level 2)

- Brewing workshops in the free towns, a legacy of the medieval bourgeois economy that is about to disappear. The tavernkeeper-brewer-merchant operates on a very local scale under the control of the administrative authority of the town, a brewers' corporation, or a more or less centralised tax administration. (diagram: level 3)

- the Palatial Brewery = brewery/brewer of the royal family + beer taverns under direct royal or imperial management (taxes and income). Same economic logic as level 2, but extended to all the royal or ducal estates (farms + towns + villages + palatial staff) and directly sponsored by the central political power. The royal or ducal breweries were founded in Munich, Prague, Vienna, Copenhagen or Stockholm among the best known examples. (diagram: level 4)

- Imperial administration of grain and fermented beverages in the Austro-Hungarian Empire of the Habsburgs. Imperial policies favour the brewing and trading of beer as a source of income for the imperial treasury. In the 19th and 20th centuries, the emerging nation states took over and increased this centralized control of the manufacture and sale of beer. They created specific national tax regimes for fermented beverages and spirits, thus controlling the entire sector, from the grain field to the retail sale of the various types of beer. (diagram: level 5)

- Commercial industrial breweries.The last avatars of these transformations, the large urban or peri-urban breweries of Vienna, Prague, Plzen, Berlin, Munich or Warsaw were at the forefront of the industrial revolution in the second half of the 19 century in Europe. They negotiated the protection of their trade with their respective state authorities while gradually freeing themselves from the local regulations inherited from the past. In the 20th century, their idustrial success considerably reduces the role and economic influence of the other brewing modes, until the recent resurgence of the latter some decades ago (garage beers, micro-brewery, pub-brewery). (diagram: niveau 6)

The Russian Empire in the 19th century offers another example of this superimposed organisation of beer brewing: kwas is the beer brewed by households and peasant communities (level 1), and the beer brewed by the large owners of agricultural estates and exempted from taxes (level 2), and also the beer brewed and sold, alongside the barley or buckwheat beer (pivo), in taverns and taxed by the provincial authorities (level 3). The large Russian cities in the Baltic have their own craft brewers and beer merchants (level 5). The Russian financiers are investing in the country's first industrial breweries (level 6). The "palatial brewery" (level 4) seems to be absent: the Romanovs and the large Russian aristocratic families ignored this activity and turned to the more lucrative distillation of alcohol.

The following pages provide some detailed examples of the first and oldest economic and historical level of the beer brewing. It was born with the first villages and their inhabitants gathered around their life-sustaining granaries.