The Great Mongolian Confederation of Central Asia

In 1218, Gengis Khan turns his gaze to the west. In September 1219, he attacked the Muslim-dominated Turkish empire of Khwarezm, centred on present-day Uzbekistan. His campaign is punctuated by terrible massacres. Two years after the death of Genghis Khan in 1227, his third son Ögödei succeeds him and launches the great campaign of Europe, between 1236 and 1242. The armies of the Russian, Polish and Hungarian principalities are swept away. The Mongols reach the Adriatic. In 1259, after having devastated Lithuania, 20,000 Mongols attack and plunder Poland again. In 1265, they attack Greece and devastate Thrace. The Byzantine Emperor is powerless. In 1271 and 1274, raids against Bulgaria, in 1275 and 1277 against Lithuania. In 1284, another invasion of Hungary again, the cities of Transylvania are devastated. In 1287, Poland is once more devastated. In 1293, Serbia has to recognise Mongol suzerainty.

After the death of Gengis Khan (1227), the largest of the empires ever conquered is divided around 1260 into 4 ulus (countries, regions) each governed by one of the sons of the Great Mongol. To the N-W, the Golden Horde (Russia, Eastern Europe), to the S-W the Khanate of the Ilkhans (Persia = Iran+Iraq+Syria), to the N-E the Great Khan (Mongolia-Chine-Vietnam) of the dynasty Yuan, to the Centre the Khanate of Djaghataï (Central Asia). This immense empire extends from the Pacific to the Black Sea, from Siberia to the borders of India.

The Mongolian cavalry and archers are fearsome. The Mongolian conquest rhymes with mass massacres and destruction of cities. Europe is unable to have a common and coordinated response. Each kingdom defends itself alone against the horsemen of the apocalypse. Part of European chivalry is engaged in the crusades in Syria and Palestine. The response of the European royal courts will be diplomatic. The embassies to the Khans seek an agreement or a possible alliance of Christian and Mongolian forces against the Muslims. It is to these Europeans emissaries that we owe a better knowledge of the organisation and customs of the Mongolian peoples in the 13th century. One of them wrote a meticulous and impartial description on his return from his long trip within the new conquered Mongolian territories of central Asia.

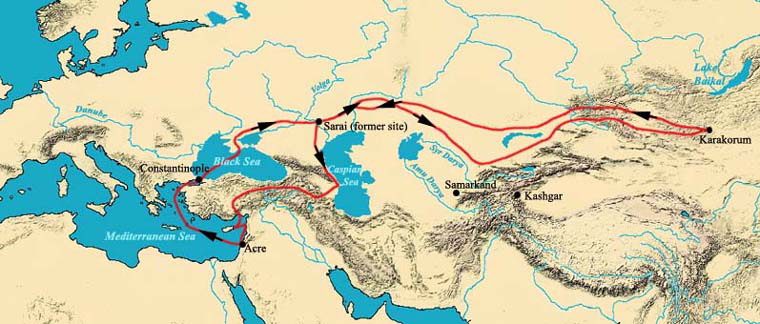

The Franciscan monk William of Rubruck (1215-1295), his Flemish hometown, left for the Mongols from southern Russia in 1253. He was ambassador of the French king Louis IX, then engaged in the 7th Christian crusade in Palestine. Leaving from St John of Acre and Constantinople, William of Rubrouck crosses, with another brother and some Tartar guides, the whole country of the Tatars until Karakorum, north of the Gobi desert, in present-day Mongolia. A simple camp in the time of Genghis Khan, Karakorum became the capital city of the Mongolian empire with his son Œgödäi. His successor, the emperor Möngku embellished and enlarged the city.

The monk's embassy at the Mongolian court is a failure, like those that preceded or will follow it. The Great Khan is willing to recognise the Christian kings, but as his own vassals! The Christian chiefs must bow to the authority of the Great Khan who considers himself their "emperor", their Khan.

The journey of Wiliam of Rubrouck, on the other hand, was a scientific success. Returning in 1255 after a journey of 16,000 km, he described in detail what he had seen in his report to King Louis XI, " Voyage dans l'empire mongol ": the geography of the countries and the Asian steppe, the customs of the peoples, the political systems, the merchant circuits, etc.

Two topics concern us:

- What do the Tatars, i.e. the peoples of Central Asia that G. de Rubrouck meets and observes, drink?

- What fermented beverages are drunk at the court of the Great Khan, emperor of the Mongols ?

What do we learn?

- The alcoholic beverage of the pastoral peoples of Central Asia is the fermented milk. Koumis is their identity drink. It embodies their way of life and encapsulates their main cultural values: mobility, life under the tent, economic wealth based on herds, and the centrality of the horse.

- Nevertheless, the pastoralists of Central Asia did not disregard the other fermented beverages, mainly beer. They bartered with their southern farming neighbours: meat, skins, skins and fermented milk for grain, textiles, pottery and beer. At the court of the Great Khan, the world's four main fermented beverages are served: fermented milk, millet or rice beer, grape wine and mead.