The prehistory of the European beer brewing basin

A. The Neolithic period in Europe

The European beer brewing basin can be qualified as a secondary basin if we consider that three major and related innovations originated in South-West Asia for this region of the world: archaic brewing, the cultivation of cereals and the transition of populations to a Neolithic way of life.

Cereal growing and livestock farming came from Anatolia, Syria and the Levant around 6500 BC, following two routes of diffusion in Europe. The route of the Mediterranean coast passes through Cyprus, southern Anatolia, Greece, the Dalmatian coast and southern Italy. The Balkan route passes through the straits of the Bosphorus and the Dardanelles, moving towards Central Europe and up the Danube basin towards Northern Europe. These two main axes of diffusion reflect two archaeological cultures marked by a style of pottery, the so-called Cardial or Printed Culture and the so-called Linear Pottery Culture or LBK (LinearBandKeramik).

A third diffusion of the Neolithic period originated north of the Black Sea and seems, without any certainty to date, to have an autochthonous origin on the fertile tchernoziom lands between Dnieper and Volga.

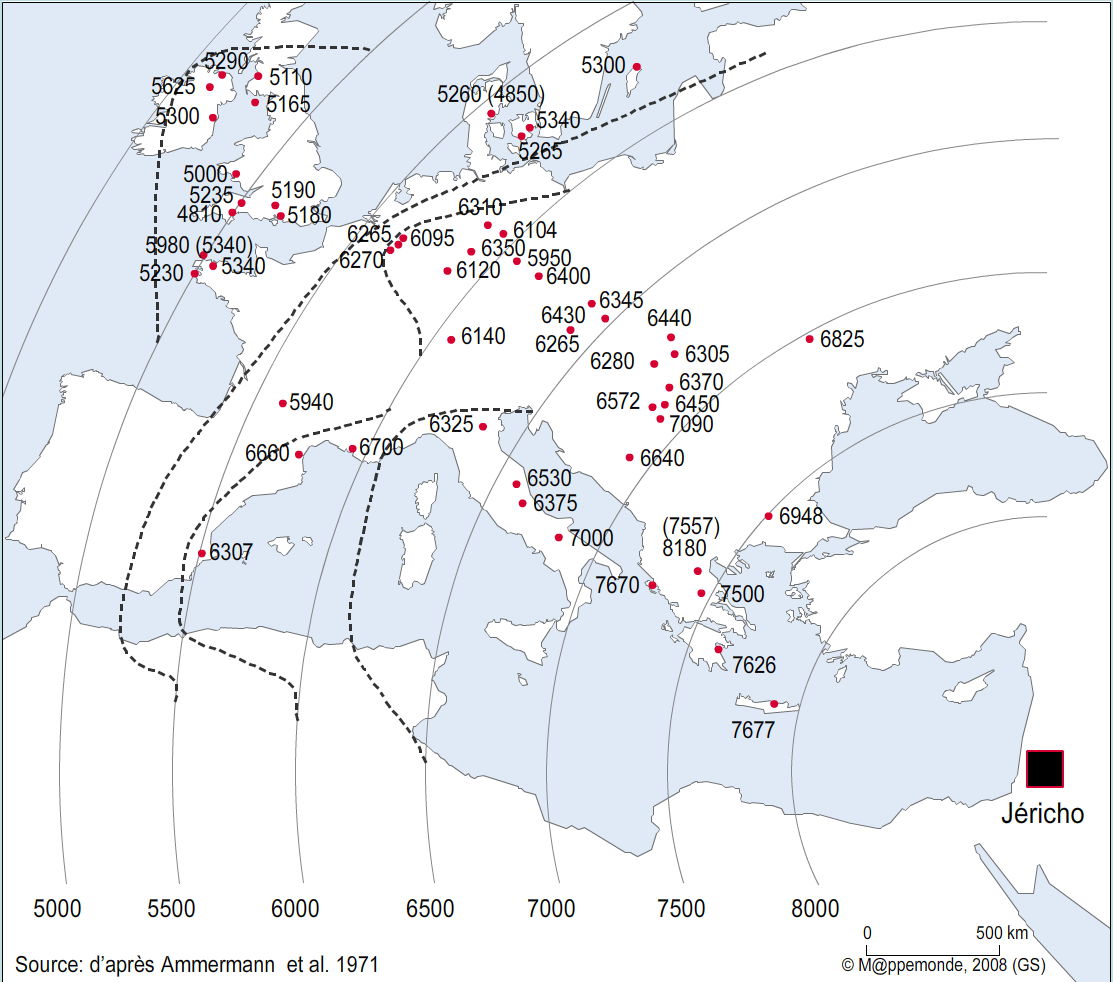

The Neolithic advance in Europe after Ammerman 1971 (fig. 6). Dates are B.P. (date BP - 2000 ≈ date BC). Red dots = archaeological sites

The Neolithic advance in Europe after Ammerman 1971 (fig. 6). Dates are B.P. (date BP - 2000 ≈ date BC). Red dots = archaeological sites

The Mediterranean flow is spreading at a regular rate, the modelling of which calculates the value ≈1km/year between Anatolia and the extreme Atlantic tip of Europe, calculations reflecting archaeological data (Fort, Pujol, Cavalli-Sforza 2004). On the contrary, the progression of the Danubian flow is not regular. Three major halts affect the spread of the main Neolithic features heading towards northern Europe: around 6200 BC in central Europe, 5400 BC towards Scandinavia and 5700 BC towards the northern Europe. They coincide with cold climatic episodes and presumably the adaptations of plants to cultivation and agricultural techniques, and the main évolutions of social strategies. The neolithisation of Europe, well understood as a whole, is the subject of much research to detail its regional modalities and to better understand the interactions between farmers and hunter-gatherers, the latter having adapted and maintained for almost 4 millennia.

Grindstone, toast, cereals and small apples, clay pots and wooden vessels found at Neolithic sites in Switzerland

Grindstone, toast, cereals and small apples, clay pots and wooden vessels found at Neolithic sites in Switzerland

The most recent genetic studies show that the initial human group from Anatolia is homogeneous (EEF group, Early European Farmers). In the Balkans, it intermingles with hunter-gatherers (7-11%) before splitting into Mediterranean and Danubian groups (Haak et al. 2010). Having reached the Atlantic coast two millennia later, these two populations retain a great genetic homogeneity. Miscegenation with hunter-gatherers encountered along the way has remained very limited for the male population. The most common lineage of Y chromosomes in the Neolithic male population comes from a single Anatolian source in the early Neolithic. Corsica and Sardinia are a sanctuary of this ancient DNA. On the other hand, mitochondrial DNA transmitted exclusively by females is more diversified and contains a significant proportion of genes from hunter-gatherers of the Mesolithic. These results suggest that male farmers mated with indigenous women hunter-gatherers much more often than female farmers mated with hunter-gatherers. Explaining this phenomenon generates much speculation. We are far from understanding the social behaviour of Neolithic societies, often abusively compared to the so called "primitive" societies described by ethnologists.

Reconstitutions of Ötzi (who lived in the Alpine Copper Age around 2590 BC), bearer of the haplogroup ADN-Y G2a which predominates among the first farming communities

Reconstitutions of Ötzi (who lived in the Alpine Copper Age around 2590 BC), bearer of the haplogroup ADN-Y G2a which predominates among the first farming communities

These same genetic studies show that among the first farming communities in Balkan and Central Europe, the female population is larger. The reasons for this are not obvious: higher male mortality, increasing sedentariness, polygyny, or conversely monogamy + patrilocality?

Furthermore, the genetic contribution of hunter-gatherer groups becomes significant again between 5,000 and 3,000 BC, proof on the one hand that they have not been replaced, on the other hand that interactions with farmers play a central role in the neolithisation of Europe.

The neolithisation of Europe is a complex, arrhythmic and heterogeneous process. Archaeology and genetics provide ample evidences of cultural and technical exchanges between hunter-gatherers and farming groups. DNA has revealed that Neolithic farmers mix with hunter-gatherers wherever their progress is slowed down. When agriculture is no longer a reliable food technique, farmers return to hunting and gathering, taking advantage of the hunter-gatherers' knowledge of the environment and experience. These two groups have evolved together and created new cultural configurations which partly explain the dynamism of the European neolithic phenomenon. The protohistory of the brewery is made up of back and forth, of technical progress (malting, mastery of cooking, fermentations, beer ferments (?), beer preservation) spread over several millennia and based on other technicalities (pottery, milling, kiln, etc.), and above all on the knowledge of the plant environment. Beer is not only brewed with cereals. Starchy tubers and starchy fruits are good sources of starch for the brewing process.

Model of a fortified Copper Age village at

Model of a fortified Copper Age village atLos Millares, Spain

The European neolithisation is characterised by specialisation in livestock farming with the development of real herds and the use of animals for work, the domestication of the horse (around 4000 BC) and the chariot, the use of the hoe and ard plough, the exploitation of flint and copper mines, a specialised craftsmanship and the manufacture of copper objects (around 7000 BC in Serbia, 3500 BC in Western Europe). The societies start to bring out hereditary upper classes and their prestigious emblems found in tombs where women, men and children of the same family or "clan" are buried side by side and richly adorned. The appearance of more specialised crafts, fortified dwellings, villages surrounded by ditches, and large funerary monuments signals at the same time a social division, armed conflicts, and the mobilisation of collective work. Places of worship are developing without it being possible to affirm that these « new cults » are organised by an elite or are the result of a collective cognitive and mental evolution.

B. Farmers and hunter-gatherers contribute to the evolution of the beer brewing

This context brings us back to the beer brewing. Archaic beers were brewed in Europe by communities with a double heritage: that of hunter-gatherers and that of farmers from Asia. The composition of their fermented beverages inherits these characteristics: ingredients from the gathering mixed with grown cereal grains. This blend produces beers as well as wines and mead.

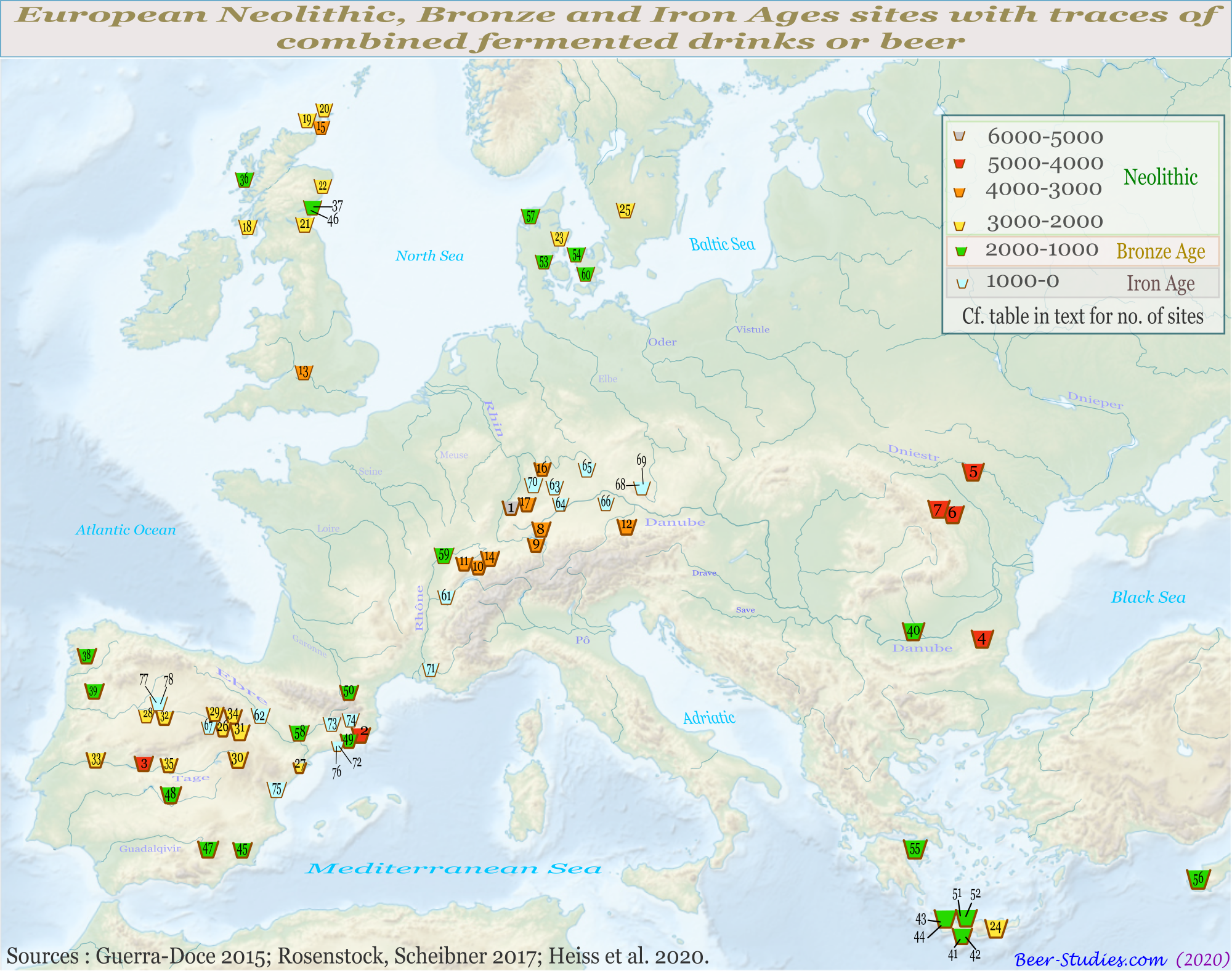

Around 5500 BC (Early Neolithic), archaeologists have discovered traces of these mixed beverages. At that time, primitive fermented beverages prevailed in Europe (Table 1 and Map 1):

- The oldest trace of "beer" to date (5500-4900) is found in Germany (Table 1, No. 1) and does not allow a distinction to be made between bread or starch-based beverage.

- The second oldest group (5000-4000 BC, 7 specimens) extends from Romania and Bulgaria to Spain, a very vast area representative of the Neolithic extension.

- The 3rd group (3900-3000 BC, 10 specimens) is mainly located in Central Europe (Germany, Austria, Switzerland) with an extension to Northern Europe (England, Scotland).

- The 4th group (3000-2000 BC, 18 specimens) illustrates the final Neolithic in Northern Europe (Scotland, Denmark, Sweden), and Mediterranean Europe (Spain, Crete).

- The 5th group belongs to the Bronze Age (2000-1000 BC, 25 specimens) and covers almost all of Western Europe.

- The 6th group is that of the Iron Age (1000-200 BC, 18 specimens). It covers Germany, Spain and France.

The map below does not draw a geography of archaic beers in Europe. The number of archaeological sites is too limited. Above all, the analyses of fermented beverages are still too sparse to support a protohistory of their spread from Anatolia across Europe. The question of whether Europe is home to several centres of diffusion of brewing techniques is more than premature. It is still impossible to say when and where the beer family broke away from the primeval base of the blended fermented beverages.

However, some striking data can be pointed out. The "bread-beer" complex is attested as early as the 6th millennium in the heart of Europe (site No1). The 2nd group illustrates at the 5th millennium both the Danube route (sites No 4, 5, 6, Bulgaria, Moldavia, Romania) and the extreme point of the Mediterranean route (sites No 2 and 3 in Spain). Brewing techniques have therefore followed these two main migration routes. With sites no. 13 and 15, starch-based fermented beverages are known in Northern Europe (England, Scotland) at a very remote time (4th millennium).

European map of archaeological sites with ancient beer traces (see table for the details of archaeological sites by No) Neolithic and Bronze Age sites in Europe with traces of beer.Table giving the detail and No of the sites

Neolithic and Bronze Age sites in Europe with traces of beer.Table giving the detail and No of the sites

C. A protohistory of beer in two main phases

The fisrt phase is the progressive autonomy of the 4 groups of fermented beverages which separate from their primaval base, the old fermented undifferenciated cocktail. The second phase allows the beer group to specialise itself following one of the six different brewing methods.

Andrew Sherratt has focused on technical inventions that emerged after the first wave of neolithisation which included primitive agriculture, livestock farming and partial sedentarisation. A "Second Neolithic Revolution", a second wave originating again in South-West Asia around 4500 BC, have reached Europe by the same routes taken 2 millennia before. It brought dairy products, wool, animal traction, wheels and the use of fermented beverages or narcotics. This constituted a new stage in the exploitation of the environment. Given the very old dates of the fermented beverages recorded in the Table, it is doubtful that the use of primitive fermented beverages, more or less undifferentiated, waited until the 5th millennium to appear in Europe. Archaeology proves that they were more precocious in Europe, attested already in Central Europe during the mid 6th millenium.

Nevertheless, the specialisation of the primitive fermented beverages, their split from the primival base, could correspond to this Second Neolithic Revolution such as explained by Sherratt: an acceleration of social transformations through new techniques. Having become autonomous, the group of the beers as fermented beverages based on starch mainly, may well have speed up collective practices of alcohol consumption and at the same time promote the cultivation of cereals for brewing. From the 3rd millennium onwards, traces of beer are often discovered in ritual contexts: tombs, pits of ritual deposits, ceremonial sites, etc. (No 11, 23, 25-28, 31-35, 37-40, 44-46, 50-51, 53-54, 57, 60, …).

In Eastern Europe, this "Second Neolithic Revolution" meets a new wave of human migration from the eastern steppes. This phenomenon, highlighted by genetic studies, meant that groups of nomadic pastoralists mixed with European farmers and then replaced nearly 60% of the male lines of Neolithic farmers before the Bronze Age, around 3000 BC. The European Neolithic is thus punctuated by two major migrations: the arrival of the first farmers in the Balkans around 6500 BC, followed by the arrival of pastoralists from the eastern steppes around 3000 BC. This second migration is attributed to the proto-Indo-Europeans originating from the Pontic steppes extending north of the Black Sea and the Caspian Sea (Yamnaya culture). These vast movements of people and cultures from Eastern Europe coincide with the rapid expansion of the Bell Beaker Culture (Bell-shaped pottery, Bell-Beaker or GBK) throughout Europe. This major event has an unforeseen consequence: the arrival in Europe of fermented milk, the 4th beverage forming the basis of primitive fermented beverages.

In 2018, a major study of genomic formation in South and Central Asia found that the vast majority of Indo-European speakers living in both Europe and South Asia have many ancestry groupings related to pastoralists of the Yamnaya culture. The expansion of pastoralists into Central Asia and northern India in the second millennium is linked to the question of "proto-Indo-European", the ancestral language of all modern Indo-European peoples.

Our investigation is now in the hands of linguists. Indo-European peoples (here we tell about speakers of the Indo-European languages) shed new light on the archaic brewing in Europe. According to the researchers, they spread from the Eurasian steppe around 4000-3500 years ago, or from Anatolia around 7000-6500 years ago. These dates more or less coincide with those of geneticists for Eurasia, but not for Anatolia. Their fermented drinks? Beer (*haelut-), mead (*medhu-), wine (*woino/*weino) and fermented milk (*súleha-). When the Indo-European vocabulary distinguishes these 4 fermented drinks, they then constitute 4 groups of dictinct beverages that have split off from the primeval foundation of the combined fermented drinks.

Which one is the oldest?

Indo-European linguistics stumbles over these questions of technical genesis and priority between fermented beverages. No wine without addition of honey, no beer without fruit, no fermented milk without yeast-bearing plants specialising in the alcoholic fermentation of lactose, and so forth. According to the geographical area (Indo-Iranian, European, Central Asian), the nature of the texts and the progress of archaeological studies, one fermented beverage seems to precede the 3 others[1], however never the same one depending on the geographical area or time period. The existence of undifferentiated fermented beverages for thousands of years makes this logic obsolete: no fermented beverage precedes another one, all come from the same original base.

The question becomes: at what stage did the 4 Indo-European beverages separate from the common trunk of hybrid fermented beverages? Around 4000 BC genetics and linguistics answer together.

Let us return to Europe. The arrival of Indo-European pastoralists and speakers around 4000 BC initiates a slow process of specialisation of fermented beverages in Europe. Coming from the East, it spreads towards the West at an unknown speed. It is contemporary with deep social changes marked by hierarchisation, craft specialisation and new techniques. The improvement of brewing techniques is undoubtedly one of them, especially the malting of cereals, but the whole process still remains to be analysed.

Around 2000 BC, the Bronze Age witnessed other evolutions, one of which concerned brewing. Having become autonomous, the family of beers became specialised from a technical but above all a social point of view. The Celtic culture offers one example. The warlords did not drink the same beer as the submissive populations. The farmer's beer is not the clan chief's beer. Princes and war chiefs consume mead or strong beer mixed with honey. Their trading contacts with the Mediterranean world would sometimes lead them to replace this strong beer with grape wine, proof that a hierarchy of fermented beverages was already operating among the Celtic peoples. Michael Dietler (1990 and 1994) has pointed out that these drinking manners mark a strong social differentiation (beer remains the ordinary beverage of peasants and slaves) and the fact that the adoption of Mediterranean wine does not result from an imitation of Greco-Latin cultures (the symposium) but from a reinforcement of power relations within the Celtic world from 600 BC onwards[2].

The arrival of the pastors has another long-term consequence. Eastern Europe remains characterised by sour beers to this day. In modern times they are called kwas, braga, ... These are farmhouse beers, brewed at home with rye, oats, millet or so-called "poor" grains and graminae. They have an obvious link with the fermented milks of pastoralists whose descendants are found in the koumys or the kefir[3]. For its own part, Northern Europe has long maintained this tradition of domestic beers, the protohistory of which remains to be written. The Scandinavian skyr, a fermented milk, bears witness to the protohistoric link between beer and fermented lactic beverages.

The archaic traces of beer discovered in Spain are numerous and cover several millennia. They reflect the intensity of the archaeological excavations. The two great waves of European migrations can be read in the two chronological sets of the corpus: the first one (no. 2-3) arrives around the 5th millennium, the second from the 3rd millennium onwards and enters fully into the wave of the Bell Beaker Culture (no. 26 ff.). Here we would have for the Iberian Peninsula the schema of the 2 stages of the protohistoric evolution of brewing: initially the common base of the blended fermented beverages, then the beginning of an autonomy of the "beer" group with the more frequent and generalised use of cereals. And much later, the third stage is the specialisation of brewing techniques within this "beer" group. Nevertheless, the diagram is simplistic: Spanish and Catalan archaeologists insist on the importance of local adaptation processes (Bell Beaker culture is neither an invasion nor a tidal wave), the role of hunter-gatherers, their techniques and social strategies.

The protohistory of European beer remains a ground to be cleared. Archaeology, analyses of pottery and starch traces, carpology and palaeogenetics regularly bring new data[4]. Its study has great significance and multiple ramifications. Bread and beer make up a solid technical couple which sheds light on technical aspects of the Neolithic period such as the advancement of cereal growing and grain processing methods, the relative control of fermentation, the role of starch among all food resources. Fermented beverages are also a special gateway to social behaviour, collective events, funerary rituals, etc. Beer, an alcoholic beverage which may be psychotropic (nos. 19 to 22, 66, 74), is an object of study which combines these two approaches: that of starch-based food technologies and that of social mechanisms.

It should be remembered that the history of beer, in its long history in Europe and elsewhere, has seen episodes of recombination of techniques, and sometimes involutions of socio-economic processes. Brewing is not separated from other fermentation technologies, such as the fermentation of dairy products by nomads and viniculture. The brewery-bakery complementarity is also very strong, without being exclusive.

D. List of archaeological witness sites in Europe known to date (2020)

List of the oldest traces of grain-based fermented beverages in Europe. (see CARTE)

| PROVISIONAL LIST OF ARCHAEOLOGICAL SITES THAT HAVE PROVIDED BEER TRACES or BREWING INDICATIONS during NEOLITHIC, BRONZE & IRON AGES in EUROPE (2020) | ||||||

| No | Site | Country | Period | Context | Residues/Clues | Interpretation |

| 1 | Stuttgart-Zuffenhausen | Germany | Linear Pottery Culture (LBK) 5500-4900 BC | Tomb | Starch residues and yeast cells in a vessel for a burial. | Possible fermentation of bread and starchy beverage (Paret 1935) |

| 2 | Cova de Can Sadurní (Barcelona) | Spain | Early Neolithic Postcardial 5th mil. cal BC | Domestic occupation and burial place | Starch granules distorded by malting; phytoliths from festucoides cereals and barley (Hordeum vulgare); oxalate. | Beer (Blasco et al. 2008) |

| 3 | Dolmen de Azután (Toledo) | Spain | Neolithic 5th mil. cal BC | Domestic occupation under a megalithic tomb | Cerotic acid; pollen from heather (Erica sp.), Cistus(Cistaceae) and oaks (Quercus sp.); frustules of diatoms. | Honey and mead (Bueno et al. 2005a). |

| 4 | Ovcarovo | Bulgaria | Poljanica 4500-4000 BC | Settlement | Grain silo, kiln, millstones, hearth, shards of 0.5 to 2 litres containers and filters. | Possibly, an equipment for brewing beer (Bailey 1996, 150). |

| 5 | Jablona I | Moldavia | Cucuteni 4500-3000 BC | Settlement | Baked bread and breadcrumb idols | Link with soups or fermented beverages (Monah 2012, 12). |

| 6 | Izvoare-Neamt | Romania | Cucuteni-B 4500-4000 BC | Settlement | Baked bread and bread-shaped idols | Link with soups or fermented beverages (Monah 2012, 12). |

| 7 | Calu | Romania | Cucuteni-B 4500-4000 BC | Settlement | Baked bread and bread-shaped idols | Link with soups or fermented beverages (Monah 2012, 12). |

| 8 | Sipplingen-Osthafen (lac de Constance) | Germany | Neolithic 3910 BC | Settlement | Malting detected with a new method (aleurone layer structure) | Beer, fermented beverages (Heiss et al. 2020) |

| 9 | Hornstaad-Hörnle (lac de Constance) | Germany | Neolithic 3600 BC | Settlement | Malting detected with a new method (aleurone layer structure) | Beer, fermented beverages (Heiss et al. 2020) |

| 10 | Montmirail | Switzerland | Cortaillod 3719-3699 BC | Settlement | Baked bread and bread-shaped simulacrums | Possible link with soups or fermented beverages (Wärhen 1984, 1989) |

| 11 | Twann | Switzerland | Cortaillod 3560-3530 BC | Settlement | Baked bread and bread-shaped simulacrums | Possible link with soups or fermented beverages (Wärhen 1984, 1989) |

| 12 | See am Mondsee | Austria | Mondsee Culture 3500-3000 BC | Settlement | Baked bread and bread-shaped simulacrums | Possible link with soups or fermented beverages (von Stokar 1951) |

| 13 | Yarnton | England | Neolithic 3500-3000 BC | Settlement | Baked bread and bread-shaped simulacrums | Possible link with soups or fermented beverages (Dineley and Dineley 2000; Dinely 2004) |

| 14 | Zurich Parkhaus Opera | Switzerland | Late Neolithic 3176-3153 BC | Settlement | Bread baked and malted detected with a new method | Beer, fermented beverages (Heiss et al. 2017, 2020) |

| 15 | Barnhouse (Mainland Orkney) | Scotland | Neolithic 4th mil. cal BC | Settlement | Lipides d'orge, sucres non identifiés, résines d'écorce, matériel végétal non identifié, lait de bovins et viande de bovins | Beer (Dineley 2004; Jones 2002) |

| 16 | Schernau | Germany | Neolithic Bischeimer Gruppe 3500-3000 BC | Pits in a settlement | Finds of (naked) barley malt in pits with charred plant remains | Malted beer (Hopf 1981) |

| 17 | Remseck-Aldingen | Germany | Neolithic Schussenreider Culture 3500-3000 BC | Pits in a settlement | Finds of (naked) barley malt in pits with charred plant remains | Malted beer (Piening 2005) |

| 18 | Machrie Moor (Isle of Arran) | Scotland | Neolithic 3rd mil. cal BC | Ceremonial site | Pollens and cereal macrorrests | Either mead or beer (Dineley and Dineley 2000) |

| 19 | Skara Brae | Scotland | Neolithic 3rd mil. cal BC | Settlement | Treatment of cereals with water, large containers sunk into the ground (grooved ware), barley remains, psychotropic plants including black henbane | Either mead or beer (Dineley and Dineley 2000; Dineley 2004) |

| 20 | Knap of Howar | Scotland | Neolithic 3rd mil. cal BC | Settlement | Treatment of cereals with water, large containers sunk into the ground (grooved ware), barley remains, psychotropic plants including black henbane | Either mead or beer (Dineley and Dineley 2000; Dineley 2004) |

| 21 | Balbridie | Scotland | Neolithic 3rd mil. cal BC | Settlement | Treatment of cereals with water, large containers sunk into the ground (grooved ware), barley remains, psychotropic plants including black henbane | Either mead or beer (Dineley and Dineley 2000; Dineley 2004) |

| 22 | Balfrag / Balbirnie | Scotland | Neolithic 3rd mil. cal BC | Settlement | Treatment of cereals with water, large containers sunk into the ground (grooved ware), barley remains, psychotropic plants including black henbane | Either mead or beer (Dineley and Dineley 2000; Dineley 2004) |

| 23 | Refshøjgård (Folby parish, East Jutland) | Denmark | Earliest Single Burial Culture 2900-2700 BC | Tomb | Starch granules in a non-carbonized crust | Beer (Klassen 2008) |

| 24 | Phournou Koryphe (Myrtos, Crete) | Greece | Early Minoan IIB 2900–2300 BC | Settlement | Tartaric acid; tree resin/calcium oxalate | Resinated wine / Barley beer (McGovern et al. 2008) |

| 25 | Hamneda | Sweden | Late Neolithic 2300-1800 BC | Stone cist | Pollen grains of cereals (Hordeum sp. and Triticum sp.) and rosebay willowherb (Epilobium angustifolium), among others | Flour, bread, porridge, gruel or beer (Lagerås 2000) |

| 26 | Abrigo de Carlos Álvarez (Soria) | Spain | Bell Beaker (Ciempozuelos) 2600-2000 BC | Shelter with schematic art | Starch granules (Triticeae) affected by enzymatic attack; cereal phytoliths; silica skeletons of wheat | Beer (Rojo et al. 2008) |

| 27 | Calvari d´Amposta (Tarragona) | Spain | Bell Beaker (Maritime) 2600-2000 BC | Burial | Residues suggestive of barley beer; traces of the alkaloid hyoscyamine | Hallucinogenic beer with the addition of a specie of the Solanaceae (Fábregas 2001) |

| 28 | La Calzadilla (Valladolid) | Spain | Bell Beaker (Ciempozuelos) - 2600-2000 BC | Ritual pit with two human ribs within | Phytoliths of festucoide cereals; silica skeletons of barley (Hordeum vulgare); starch granules (Triticeae) affected by enzymatic attack; cerotic acid | Beer with honey, mead, beeswax applied as a sealant (Guerra 2006b) |

| 29 | Los Dolientes I (Soria) | Spain | Bell Beaker (Ciempozuelos) 3rd mil. cal BC | Settlement | Silica sclereids of the Rosaceae family, possibly wild pear (Pyrus) | Pear jelly, juice or cider (Rojo et al. 2008) |

| 30 | Loma de la Tejería (Teruel) | Spain | Bell Beaker (Ciempozuelos) 2600-2000 BC | Mining camp | Oxalate; starches altered by malting and enzymatic attack; yeasts; phytoliths of cereals (Hordeum sp.) | Beer and fruit wine? (Montero and Rodríguez de la Esperanza 2008) |

| 31 | Peña de la Abuela (Soria) | Spain | Bell Beaker (Maritime) 2600-2000 BC | Burial | Starch granules affected by enzymatic attack; cereal phytoliths; silica skeletons of wheat | Wheat beer (Rojo et al. 2006) |

| 32 | Perro Alto (Fuente Olmedo, Valladolid) | Spain | Bell Beaker (Ciempozuelos) 2600-2000 BC | Burial | Starch granules affected by enzymatic attack; phytoliths of festucoide cereals; silica skeletons of wheat (Triticum sp.) | Beer (Delibes et al. 2009) |

| 33 | Trincones I (Cáceres) | Spain | Bell Beaker (Ciempozuelos) 2600-2000 BC | Burial | (no indication) | Barley preparation (beer?) (Bueno et al. 2010) |

| 34 | Túmulo de la Sima (Soria) | Spain | Bell Beaker (Maritime) 2600-2000 BC | Burial | Starches altered by malting and enzymatic attack; yeasts; silica skeletons of wheat | Beer (Rojo et al. 2006) |

| 35 | Valle de las Higueras (Toledo) | Spain | Bell Beaker (Ciempozuelos) 2600-2000 BC | Burial | Residues suggestive of barley beer and mead. | Beer (Ciempozuelos bowl) and mead (plain bowl) (Bueno et al. 2005b) |

| 36 | Kinloch Bay (Island of Rhum) | Scotland | Neolithic 2nd mil. cal BC | Settlement | Cereal-type pollen, ling (Calluna vulgaris), royal fern (Osmunda regalis) and meadowsweet (Filipendula ulmaria). | Ale (Wickham Jones 1990) |

| 37 | Ashgrove (Fife) | Scotland | Bell Beaker 2nd mil. cal BC | Burial cist | High proportions of lime tree pollen (Tilia cordata) and pollen from flowers such as meadowsweet (Filipendula ulmaria), heather (Calluna), ribwort plantain (Plantago lanceolata). | Mead made from lime honey and flavoured with flowers of meadowsweet (Dickson1978) |

| 38 | Devesa do Rei (La Coruña) | Spain | Bell Beaker 2nd mil. cal BC | Ceremonial site | Cerotic acid; pollen from heather (Erica sp.), Cistus (Cistaceae) and oaks (Quercus sp.); frustules of diatoms. | Honey and mead (Prieto 2005) |

| 39 | A Forxa (Orense) | Spain | Early Bronze age 2000-1000 BC | Burial | Oxalate; starches affected by malting and enzymatic attack; yeasts; cereal phytoliths | Beer (Prieto Martinez, Juan Tesseras, Matamala 2005) |

| 40 | Sucidava-Celei | Romania | Copper to Bronze ages in S-E Europe 3000-800 BC | Tell with burial | Bread with roasted barley or wheat grains. | Potential fermentation of bread or starchy beverages (Monah 2002, 4, fig. 1, 13) |

| 41 | Apodoulou (Crete) | Greece | Middle Minoan 1900-1600 BC | Settlement | Tartaric acid | Resinated wine (McGovern et al. 2008) |

| 42 | Monastiraki (Crete) | Greece | Middle Minoan 1900-1600 BC | Palace center | Tartaric acid; pine resin | Resinated wine (McGovern et al. 2008) |

| 43 | Kastelli (Chania, Crete) | Greece | Late Minoan IA 1600-1500 BC | Palace complex | Tartaric acid; resin; beeswax | Mixed fermented beverage or resinated wine (McGovern et al. 2008) |

| 44 | Splanzia (Chania, Crete) | Greece | Late Minoan IA 1600-1500 BC | Cult area | Tartaric acid; calcium oxalate; fermented honey? | Resinated wine, mead, barley beer (McGovern et al. 2008) |

| 45 | Fuente Álamo (Almería) | Spain | El Argar culture 2nd mil. cal BC | Burial | Tartrates | Grape/pomegranate wine (Juan-Tresserras 2004) |

| 46 | North Mains (Strathallan, Perthshire) | Scotland | Bronze Age 2nd mil. cal BC | Burial | High percentages of Filipendula (meadowsweet) pollen and relatively high percentages of cerealia pollen in a food vessel. | Either a porridge of cereals (e.g. frumenty) or a fermented ale, flavoured with meadowsweet flowers or extract (Barclay 1983) |

| 47 | El Malagón (Cúllar) | Spain | Bronze Age 2000-1000 BC | Domestic settlement | Germinated grains. | Possible beer brewing (Hopf 1991) |

| 48 | Motillo del Azuer (Ciudad Real) | Spain | Bronze Age 2000-1000 BC | Domestic settlement | Germinated grains.. | Possible beer brewing (Hopf 1991) |

| 49 | Can Sadurní (Barcelona) | Spain | Middle Bronze age 1600-1200 BC | Domestic settlement | Starch granules affected by enzymatic attack; phytoliths of festucoide cereals; silica skeletons of barley (Hordeum vulgare); yeasts; frustules of diatoms. | Beer (Blasco 2008) |

| 50 | Prats (Canillo, Andorra) | Andorra | Middle Bronze age | Ritual pit | Starches (Triticeae) affected by enzymatic attack; silica skeletons of emmer (Triticum turgidum subsp. diccoco); yeasts; calcium oxalate. | Beer (Yáñez et al. 2001–2002) |

| 51 | Armenoi (Crete) | Greece | Late Minoan IIIA-B, 1600-1000 BC | Cemetery | Calcium oxalate; beeswax; tartaric acid. | Mixed fermented beverage (McGovern et al. 2008) |

| 52 | Chamalevri (Crete) | Greece | Late Minoan IIIC1 1350-1100 BC | Settlement | Tartaric acid/tartrate; tree resin | Mixed fermented beverage (McGovern et al. 2008) |

| 53 | Egtved | Denmark | Late Bronze Age 2nd mil. cal BC | Burial | Cowberries (or cranberries), grains of wheat, glandular hair from bog myrtle, pollen grains from lime tree, meadowsweet, white clover. | Combination of beer and fruit wine, with the addition of honey to make it stronger (Thomsen 1929) |

| 54 | Bregninge (Island of Zealand) | Denmark | Late Bronze Age 2nd mil. cal BC | Burial | Pollen from lime, meadowsweet, white clover, various Compositae and knotgrass. | Honey or mead (Nielsen 1988) |

| 55 | Mycenae (Mainland Greece) | Greece | Late Helladic A-B 1600-1000 BC | Citadel | Tartaric acid; tartrate; tree resin/cerotic acid; oxalate; tartaric acid. | Resinated wine/barley beer (McGovern et al. 2008) |

| 56 | Kissonerga-Skalia | Cyprus | Late Bronze Age 1600-1000 BC | Settlement | Calcium oxalate detected in an oven | Kiln used to dry malt (Crewe et Hill 2012) |

| 57 | Nandrup (Island of Mors) | Denmark | Bronze Age, late 2nd mil. cal BC | Burial | Pollen from lime tree (Tilia cordata) and meadowsweet (Filipendula ulmaria); white clover | Mead (Broholm and Hald 1939) |

| 58 | Genó (Lérida) | Spain | Late Bronze Age | Settlement | Starches altered by malting and enzymatic attack; silica skeletons of barley (Hordeum vulgare) and emmer wheat (Triticum dicoccum) yeasts; frustules of diatoms; lactobacteria | Beer (Maya et al.1998) |

| 59 | Planches-Près-Arbois (Jura) | France | Late Bronze Age 1200-900 BC | Cave | Concentration of barley and millet grains in pots, ungerminated. | Possible beer brewing (Pétrequin et al. 1985) |

| 60 | Kostræde (Island of Zealand) | Denmark | Late Bronze Age. ca 1100-500 BC | Hoard from a pit | Tartaric acid/tartrate; honey; birch and pine tree resins. | Imported wine; mead (McGovern et al. 2013a) |

| 61 | Saint-Romain-de-Jalionas (Isère) | France | Early Iron Age 750-700 BC | Mound | Concentration of barley and millet grains in pots, unsprouted. | Possible beer brewing (Verger et Guillaumet 1988) |

| 62 | Alto de la Cruz (Navarra) | Spain | Iron Age | Settlement | Starch granules (Triticeae) altered by malting and enzymatic attack; yeasts. | Beer (Juan-Tresserras 1997) |

| 63 | Hochdorf | Germany | Iron Age (Hallstatt) 6th century BC | Burial | Large quantities of pollen from a number of flowering herbs, mostly thyme and other plants of open countryside. | Freshly made, unfiltered mead (Körber-Grohne 1985) |

| 64 | Hohmichele-Heuneburg | Germany | Iron Age (Hallstatt) 6th century BC | Burial | Large quantities of pollen from plants with nectar-yielding flowers; honey. | Mead or a mixed drink containing honey (Rösch 1999) |

| 65 | Pfarrholz (Kasendorf) | Germany | Iron Age Hallstatt | Burial | Black wheat ale flavoured with oak leaves. | Black ale (Abels 1986) |

| 66 | Niedererlbach | Germany | Iron Age (late Hallstatt) | Burial | High pollen diversity: abundance of Filipendula, Centaurea jacea type, Mentha type, Hypericum and Thymus. | Highly concentrated, freshly prepared mead (Rösch 2005) |

| 67 | El Solejón (Soria) | Spain | Iron Age | Settlement | Starches affected by enzymatic attack; yeasts; frustules of diatoms; lactobacteria. | Beer (Maya et al. 1998) |

| 68 | Glauberg 1 | Germany | Iron Age La Tène A. 5th century BC | Burial | Large quantities of pollen from plants with nectar-yielding flowers; honey | Fresh mead of a good strength (Bartel et al. 1997) |

| 69 | Glauberg 2 | Germany | Iron Age La Tène A. 5th century BC | Burial | Large quantities of pollen from plants with nectar-yielding flowers; honey | Unidentified liquid sweetened with honey or an old mead stored in the pitcher (Bartel et al. 1997) |

| 70 | Eberdingen-Hochdorf | Germany | Between 540 and 510 BC | Settlement | Large number of husked barley grains with uniform germination and only a few other useful plants. | Possibly a ditch used for germination and/or kiln to dry/roast the malt of a Celtic brewery (Stika 1996, 2011) |

| 71 | Roquepertuse (Velaux, Bouches-du-Rhône) | France | 5th century BC | Settlement | Concentration of charred barley grains near a fireplace and an oven in a house. | Beer brewing (Bouby, Boissinot, Marinval 2011) |

| 72 | Alorda Park o Les Toixoneres (Tarragona) | Spain | Iberian | Settlement | Starch granules; phytoliths of festucoide cereals; silica skeletons of barley (Hordeum vulgare); yeasts; oxalate; diatoms; lactobacteria. | Beer (Juan-Tresserras 1997) |

| 73 | Iesso (Lérida) | Spain | Iberian | Settlement | Yeasts; oxalate | Beer (Guitart et al. 1998) |

| 74 | Mas Castelar (Gerona) | Spain | Iberian | Sanctuary | Starches altered by malting and the enzymatic attack; oxalate; yeasts; lactobacteria; diatoms; ergot (Claviceps sp.) | Beer (Juan-Tresserras 1997) |

| 75 | Torrelló del Boverot (Castellón) | Spain | Iberian | Settlement | Starch granules altered by malting and enzymatic attack; yeasts; phytoliths; oxalate. | Beer (Clausell et al. 2000) |

| 76 | Vendrell Mar o Les Guàrdies (Tarragona) | Spain | Iberian | Settlement | Starches altered by malting and the enzymatic attack; oxalate; yeasts; lactobacteria; diatoms | Beer (Juan-Tresserras 1997) |

| 77 | Carralaceña (Valladolid) | Spain | Vaccean | Burial | Starch granules (Triticeae) affected by enzymatic attack; silica skeletons of barley (Hordeum vulgare L.); oxalate; yeasts. | Beer (Sanz and Velasco 2003) |

| 78 | Las Ruedas (Valladolid) | Spain | Vaccean 2nd century BC | Cimetery | Starch granules (Triticeae) affected by enzymatic attack; silica skeletons of barley (Hordeum vulgare L.); oxalate; yeasts; hyoscyamine/glucose, cerotic acid, tartrate crystals. | Beer and a hallucinogenic beer with the addition of a member of the Solanaceae (Sanz and Velasco 2003) |

Sources (please refer to the sources below to find the complete bibliographies quoted in the last column of the above table) :

|

||||||

List of the oldest traces of grain-based fermented beverages in Europe.

(MAP of the ARCHAEOLOGICAL SITES) * * * * (Top of table)

[1] Dugan F. M. 2009, Dregs of Our Forgotten Ancestors. Fermentative Microorganisms in the Prehistory of Europe, the Steppes, and Indo-Iranian Asia and Their Contemporary Use in Traditional and Probiotic Beverages, FUNGI vol. 2:4, 16-39. «The earliest beverages may have been kvass or mead-like. “Kvass”-like and “medhu”-like cognates are present in PIE, and distributed throughout the entire range of IE languages. Cognates for “kvas,” “beer,” and “mead” long endured in European IE, and archaeological data (several types of ceramic drinking ware, e.g., Bell Beaker artifacts, etc.) are well documented throughout Europe and the Near East. Koumiss is represented by “sura”- or “hura”-like cognates in PIE and Indo-Iranian, and archaeological evidence (drinking ware) is present from the eastern range of IE. » (Dugan op. cit. p. 33)

[2] Dietler Michael 1990, Driven by Drink: the Role of Drinking In the Political Economy and the Case of Early Iron Age France, Journal of Anthropological Archaeology (9), 352-406. Dietler Michael 1994, Quenching Celtic Thirst, Archaeology 47(3).

[3] Kefir in its alcoholic version. These sour-lactic beers and fermented milks have their protohistory in Europe and Asia. Their history on these two continents is complex because of their origin, drinks of the nomadic shepherds without writing, and their resilience in Europe among peasant populations neglected by historical sources. There are a few rare punctual insights, for example the conquest of Egyptian power by the Mamelukes, slave-warrior-mercenaries from Anatolia and the northern Caucasus (The traditional beers from the fringes of the Ottoman world).

[4] Pottery known as Grooved ware has been found in abundance in recent excavations at Durrington Walls (a large circle of timberwork circa 2600 BC) and at Marden Henge in Wiltshire. Collective celebrations would have included beer and pork, subject to scientific confirmation. Jars, pots and cups were not analysed. Small quantities of Grooved ware were found at the nearby Figsbury Ring site.