The fermented beer, the decay and impurity in the Jewish religion.

Nevertheless, a ritual occasion prohibits not only the consumption of alcoholic beverages, but also any contact with whatever fermented beverage. Jewish Easter requires that participants do not consume any fermented food or beverages during the days of celebration. Fermented food and beverages are considered impure. Is it related to the drunkard's association with defilement suggested by this passage about priests and prophets who forget their mission?

« (7) But they also have erred through wine, and through beer are out of the way; the priest and the prophet have erred through beer, they are swallowed up of wine, they are out of the way through beer; they err in vision, they stumble in judgment. (8) For all tables are full of vomit and filthiness, so that there is no place clean. » (Isaïe 28:7).

No, the prescriptions go further. When a Nazarene takes a vow of abstinence to purify himself, he must no longer have the slightest contact, even accidental, with anything that can ferment spontaneously, such as grapes :

« She may not eat of any thing that cometh of the vine, neither let her drink wine or beer, nor eat any unclean thing: all that I commanded her let her observe. » (Juges 13:14). This commandment applies to a pregnant woman of a child destined to become a priest.

And in even more accurate terms, about a Nazarene[1] :

« (1) God spoke to Moses, telling him to (2) Speak unto the children of Israel, and say unto them, When either man or woman shall separate themselves to vow a vow of a Nazarite, to separate themselves unto the LORD (3) He shall separate himself from wine and beer, and shall drink no vinegar of wine, or vinegar of beer, neither shall he drink any liquor of grapes, nor eat moist grapes, or dried.(4) All the days of his separation shall he eat nothing that is made of the vine tree, from the kernels even to the husk. » (Numbers 6:3-4).

Likewise, the priest who enters the tabernacle must not have been in contact with a fermented product, let alone drunk it (Leviticus 10:9).

The ritual prescriptions require that even leaven be excluded from every house during the celebrations of Pessa'h (פֶּסַח), the Jewish Passover (Talmud, b. Pesah 3.1). This leaven encompasses everything that is fermented, i.e. hametz (חמץ). The Talmud is very precise on this subject which is both technical and ritual. The hametz designates what can ferment when one mixes one of the five cereals of the jewish tradition (wheat, barley, oats, rye, spelt[2]) with water, whether the product obtained is solid (bread, cake) or liquid (beer). The leavened bread is also one of the elements necessary to start the fermentation of the beer. At that time, baker's yeast even came from the sediments of the beer, following a production cycle that closely links the brewery and the bakery.

There thus seems to be a turnaround here compared to the Eastern cultures of the previous millennia. The fermentation of cereal products was highly valued here as a "magic" process. Fermentation brought benefits, joy and an undeniable sign of the favour that the gods granted to human beings. A positive magic, therefore.

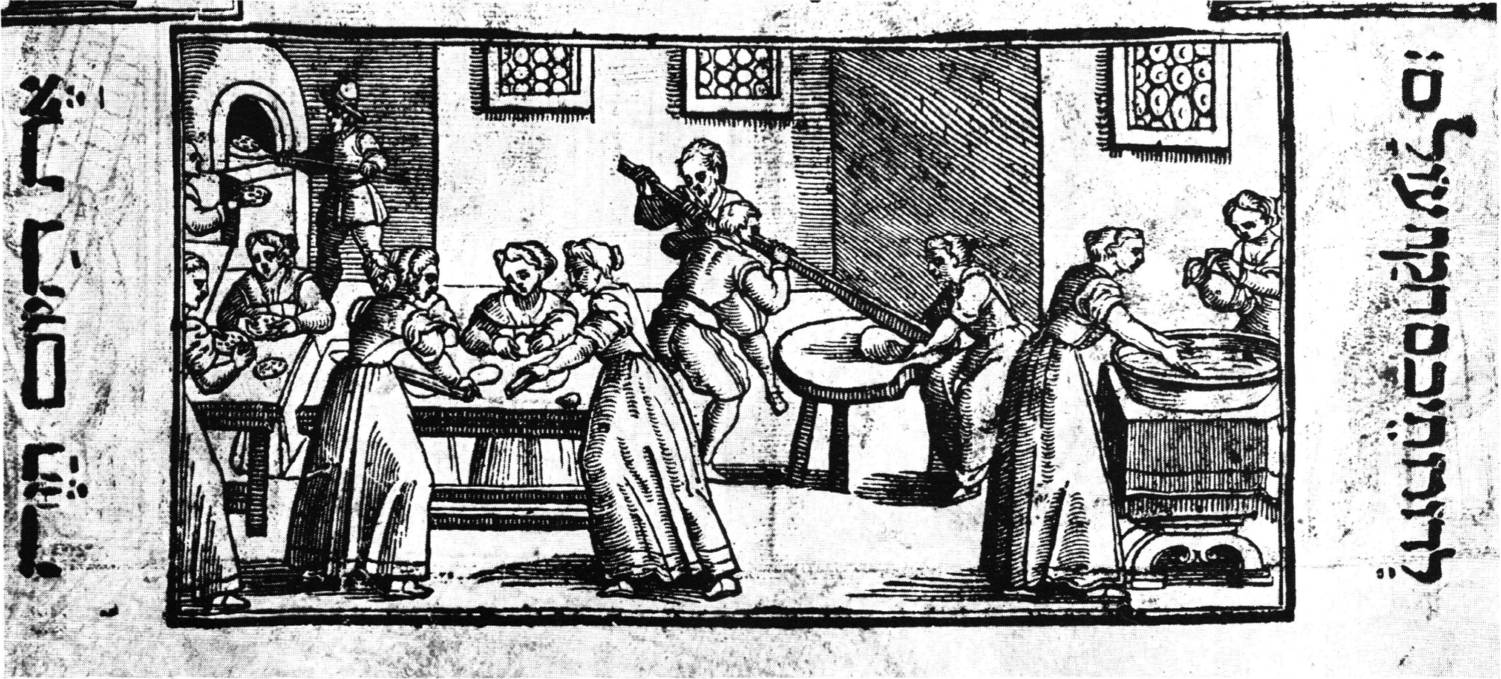

This turnaround is all the more striking as the festival of Pessa'h celebrates, during a full week, both the flight out of Egypt and the first cereal harvest of the year, at the end of March. Among the other peoples of the Near East at this time, the first fruits of the grain harvest were the cause of great collective festivities, often accompanied by cakes eating and binge drinking of beer, both prime outcomes of the new harvest. Conversely, in Jewish homes the matzaמַצָּה = unfermented, unleavened) replaces the hametz during the week of Pessa'h (Removing all leaven (chametz) during Jewish Easter).

In the Bible, coexistence and even physical proximity between the "fermented" and the sacred space (tabernacle) or house in the specific time of Passover is taboo. The fermented seems to be associated with rottenness, decay and religious impurity.

This is an unprecedented reversal of value, on the scale of the Middle East at the time. In the 1st millennium BC, the fermented beverages of all kinds, beer or date wine, were valued. But this inversion does not seem to have been either complete or extended to all areas of Jewish religious experience. How else can we understand the fact that the libation altars of the Temple are bathed morning and evening in beer and wine by priests devoted to the cult? How could the two main fermented beverages of the Israelites have their place in the sacred enclosure, even if they were excluded from the Tabernacle?

[1] This is not an ordinary vow, since it is a special protocol that lasts thirty days. According to Talmudic tradition, the main purpose of the Nazarene vow is to be a discipline against sexual temptation (Sotah 2a; Rashi) and to avoid pride (Sotah 4b). It is also seen as a means of attaining spiritual gifts (Judges 13:3; 1 Samuel 1:11), and perhaps an initiation into prophecy (Amos 2:11). By taking a Nazarene vow, a lay person also aims to a certain extent for the status of priest (Philo 1, Legum Allegoriae 249)..

[2] This restricted list of cereals authorised to produce Massoth meets a technical imperative. Do not allow the moisture accumulated in the grains to generate spontaneous fermentation between the time of harvest and the time of making the unleavened breads. Rice, tubers (potato, manioc, etc.) and other sources of starch are forbidden because the humidity they contain makes one fear a hidden alcoholic or acetic fermentation. There are maṣṣa shemoura, unleavened products made with grains whose condition (appearance of mould) and moisture (germination, spontaneous fermentation) are monitored as soon as they are harvested. This strict prohibition has not been without problems for the Jewish communities living in Asian or African countries where the 5 grains of the Law did not grow.