The historical application and the readings of the Buddhist prohibition.

About a century after the Nirvana of Buddha, the monk Yasa observes at Vesali the laxity of the local monks Vajjiputtakas [1]. The controversy is born and grows when Yasa refuses to accept donations of gold or silver. Persecuted by his co-religionists, Yasa asks for the support of the communities of West and South India. 700 monks meet at Vesali to resolve the 10 contentious points of monastic discipline. Orthodox monks and arhats (master teachers very advanced in the Path of Buddha) vote against these practices. The Vajjians withdraw from the Council to form the Mahdsaighika branch.

For the Pali tradition, these events constitute the first schism within the sangha, the original Buddhist community. The Mahdsaighika is one of the two branches through which the original Buddhist community divided, the other is the Theravadin. Some Vajjian monks, believing that the arhats adhered to an overly rigid and narrow interpretation of the rules of discipline, claimed exclusive powers and privileges for themselves. They propose the following ten points which concern first of all the nature and use of daily almsgiving (Ch'en, 213) [2] :

- - Singilonakappa, carry the salt in a horn container to use it if necessary (against the Pacittiya 38).

- - Dvangulakappa, food intake at midday (against Pacittiya 37).

- - Gamantarakappa, go to a neighbouring village and have a second meal there (against the Pacittiya 35).

- - Avdsakappa, respect for uposatha in various places within the same parish (against Mahdvagga 2.8.3.).

- - Anumatikappa, perform an act and receive its sanction afterwards (against Mahdvagga 9.3.5.).

- - Acinnakappa, use precedents as an authority on religious practices.

- - Amathitakappa, drink non-churned milk after a meal (against Pacittiya 35).

- - Jalogipatum, drink jalogi ( What is jalogi ? ) (against the Pacittiya 51).

- - Adasakam nisidanam, use of fabrics without borders for sitting (against the Pacittiya 89).

- - Jataruparajatam, acceptance of gold and silver donations (against Nissag. 18,17).

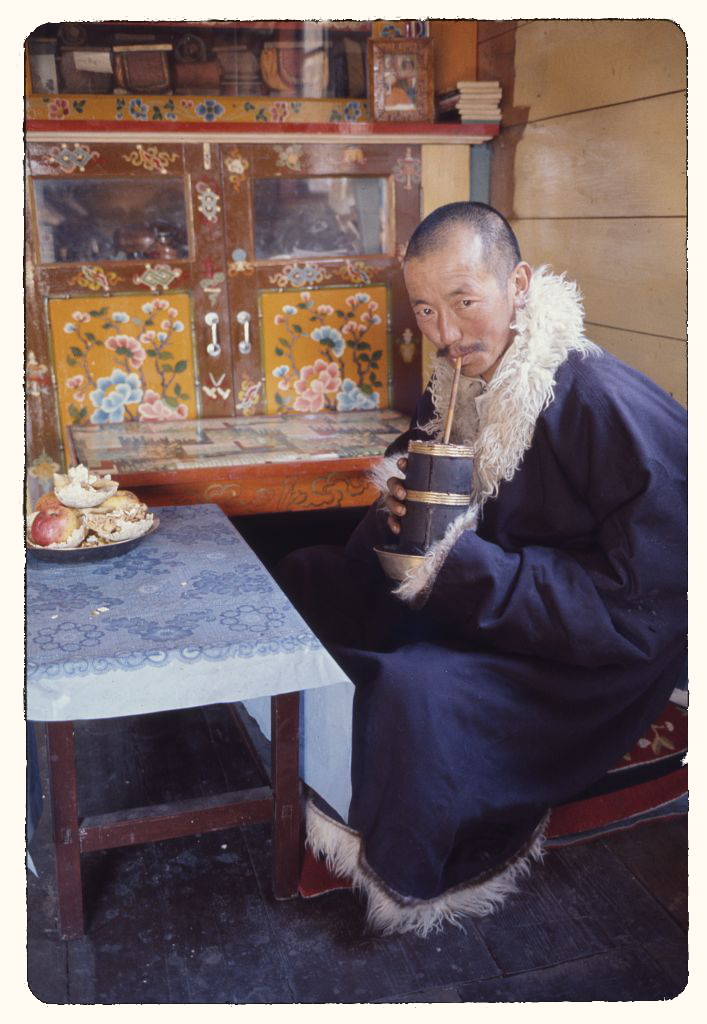

The question of jalogi is critical (point 8). The old monk Revata does not know this beverage. He asks: Jalogi? What is it ? He is answered: A fermented beverage (surā) that has not yet become intoxicating (majja), is it allowed to drink it ? No, answers Revata. On the nature of the jalogi, the versions of the Vinayas differ. Only two of them enlighten us. The one from the Sarvāstivādins says " When we live somewhere, the lack of resources makes us drink fermented beverages ". Here we find the borderline between fermented food and beverage. The Vinaya of the Mulā-Sarvāstivādins is more explicit: "Jalogi pātum is to mix a fermented beverage with water, stir the mixture and use it as a drink ". A size clue: the fermented beverage is semi-liquid, probably fermented grains since the mixture has to be stirred. The Tibetan version of the same Vinaya gives this explanation: " The monks of Vaisāli used to suckle like leeches when drinking fermented beverages, which they made legal because of illness ". Sucking like leeches (jalauka = jala + oka = the one who inhabits water)? Once all the pieces of the puzzle have been put together, we know that the intemperate monks of Vaisāli drank with a tube or a straw the alcoholic liquid obtained by diluting fermented grains with water[3]. Sipping beer through a straw was not drinking beer through a bowl, a way of getting around the definitions of drinking given by the orthodox Buddhist casuistry. Note that jalogi can also refer to a palm syrup, depending on the region of ancient India (see below). This palm sap raises the same problem for Buddhist monks: it ferments spontaneously and quickly. The borderline between sweet juice and fermented drink is easily crossed.

This way of drinking beer is nowadays very common among the populations of the Himalayas (Nepal, Tibet, Bhutan, Utar-Pradesh) and the non-Hindu populations of the Ganges valley. The fermented grains (rice, millet, barley, eleusine, maize) are diluted in a pot. The liquid part is sucked off with a tube. The monks who "sucked like leeches" are further proof that beer had a central place among all fermented beverages in Buddha's time.

In the southern regions of India and Ceylon, where the Buddhist Canon was written in pāli, the sweet sap of the palm tree or sugar cane is the source of palm or cane wine. As an unfermented raw sap, it is a refreshing non-alcoholic beverage. It is not easy to prohibit everything that is sweet, otherwise all foodstuffs will be banned. A monk eats rice, but does not drink rice beer. The relative technical complexity of the brewing process allows anyone to distinguish between these two preparations of rice, one culinary, the other for fermentation. It should be remembered that Asian cooking and brewing techniques are very similar. Ingredients and resulting products are interchangeable. Cooked rice turns into a beer ferment when it is mixed with certain amylolytic plants or fungi; the fermented, diluted and filtered rice porridge provides the beer; the residual mass, deprived of its saccharifying power, becomes a rice porridge again that is not wasted. This explains why the Buddhist rules on food and fermented beverages from starchy matters are so meticulously detailed.

The spontaneous alcoholic fermentation of sweet fruit juices, sugar cane or palm sap raises the question of the boundary between fresh sweet juice and spontaneously fermented alcoholic beverage. Just collected, palm sap and fresh cane juice are sweetened. A few hours later, they begin to ferment naturally. Where to set the border of the forbidden?

Islam will encounter the same problem with the nabid (a mash from dates or dried grapes) and the sour cereal porridges. Both can ferment spontaneously and become alcoholic (Islam world and the brewery).

Buddhism arrived in China around the 1st century BC. At the time of the Han dynasty, the Chinese were unaware of palm or cane wines, and only knew grape wine in the western marches of the empire, around the Turfan oases. The Chinese translations of the Indian Buddhist corpus maintain the distinction sura /meraya, but give it another technical meaning. For the Shih-sung Lii, a 5th century translation of the Indian Vinaya (Lii/Lü):

« is a fermented beverage made from grains, ferment-cakes made from grains and rice ". Exactly what we define as a beer. Note the explicit mention of ferment-cakes (qu, 麴), the amylolytic ferments (or beer starter) produced by a mycelium bioculture on a substrate of cooked grains or rice (Beer brewing process no. 3: amylolytic fungi).

is a fermented beverage made from grains, ferment-cakes made from grains and rice ". Exactly what we define as a beer. Note the explicit mention of ferment-cakes (qu, 麴), the amylolytic ferments (or beer starter) produced by a mycelium bioculture on a substrate of cooked grains or rice (Beer brewing process no. 3: amylolytic fungi).

« is not made of grains, fermented cakes or rice, but of stems, roots, leaves, flowers, fruits and berries " (a paraphrase of the Indian text). That is to say, wines made from fruits, berries, and sweet vegetables in general. (T23.121b) (Ch'en 1947, n. 210)

is not made of grains, fermented cakes or rice, but of stems, roots, leaves, flowers, fruits and berries " (a paraphrase of the Indian text). That is to say, wines made from fruits, berries, and sweet vegetables in general. (T23.121b) (Ch'en 1947, n. 210)

The Buddha's proscription of the fermented beverages will be respected regardless the schools and spread of Buddhism throughout Asia, and regardless the practical toils of its application. With some regional nuances: Tantric Buddhism in Tibet and Bhutan gives a place to the limited consumption of beer by monks in the celebration of rituals with lay people. In India, Tantric schools with Hindu roots will engage in a limited and ritualised use of fermented beverages by yogis.

All these rules concern monks and nuns belonging to the Buddhist communities. What about the laity?

In the Jataka, 547 long pedagogical discourses given by the Buddha on his past lives, illustrating the principles and values of his teaching, contains several warnings about the fermented beverages. They are not formally prohibited for lay people. The emphasis is on the harmful consequences of their consumption. Jataka No. 88 is entitled Surāpāna (Absorption of beer-surā). One of the didactic stories told by Buddha states the misfortunes that the drinkers of fermented beverages must expect:

There are these six dangers attached to addiction to strong drink and sloth-producing drugs: present waste of money, increased quarrelling, liability to sickness, loss of good name, indecent exposure of one's person, and weakening of the intellect. (Translation of the Digha Nikãya by Maurice Walshe)[4].

[1] Vaisali, capital of the Lichavi in Northern India, a confederation which brought together the Vajji, Mallas and Videhas tribes in a non-centralized and royalty-free form of organization which may have inspired that of the first Buddhist communities.

[2] Ch'en Kenneth 1947, A Study of The Svagata Story in The Divyavadana in Its Sanskrit, Pali, Tibetan, and Chinese Versions, Harvard Journal of Asiatic Studies 9, 207-314. jstor.org/stable/2717893.

The question of almsgiving is central to Buddhist practice. A monk has nothing but his robe and bowl to collect daily food donations from the laity.

[3] This issue has been studied by Sylvain Lévi, Observations sur une langue pré-canonique du bouddhisme, Journal Asiatique 1912, Tome XX, 508-510. => S. Lévi, Observations sur une langue pré-canonique du bouddhisme

[4] The long Discourses of the Buddha. A translation of the Digha Nikãya. Translated from the Pali by Maurice Walshe, 1987. p. 462 => Digha Nikaya (Walshe)