Your search results [1 article]

Christian Seignobos, an eminent geographer and expert of North Cameroon, has kindly granted Beer-Studies permission to publish one of his remarkable articles on beer, its manufacture, trade and social context in Maroua, one of the main towns in Northern Cameroon area. His sketches, apart from their intrinsic quality, are valuable teaching aids to explain how a saré for bilbil (saré à bilbil), an open-air cabaret-brewery, is working to those who have never set foot on African soil. At once a family's home, a vegetable garden, a "factory" for malting sorghum and brewing bil-bil beer in the open air, and a cabaret for selling it, the saré for bilbil has been an institution run mainly by women in the towns of northern Cameroon since the 1970s. Its very existence is not self-evident in a region that has been Islamised for several centuries. North Cameroon has been and remains a refuge for polytheistic farming ethnic groups. Maroua is a rapidly growing, multi-ethnic and multi-faith city, where people of very different origins and cultures live side by side, reflecting a complex and eventful history. The beer gardens, places for meetings, sharing and talking, help to maintain social peace.

Under the outward appearance of an mundane fermented beverage, the traditional beer of North Cameroon is a strange and complex object. Its manufacture and trade reveal many interwoven issues : technical (brewing a good beer), economic (what stocks of grain for beer?), social (who brews and who drinks?), political (who controls, who profits?) and religious (Islam, prohibitions, and drinking rites). Christian Seignobos unravels all these threads and reveals in the clearest possible way the downside of the cards.

Seignobos C., 2005 – "Trente ans de bière de mil à Maroua". In Raimond C., Garine E., Langlois O. (éd.) : Ressources vivrières et choix alimentaires dans le bassin du lac Tchad. Paris, IRD Éditions, coll. Colloques et séminaires : 527-561.

Croquis © IRD/C. Seignobos

Seignobos C., 2005 – "Trente ans de bière de mil à Maroua". IRD Editions

Thirty years of sorghum beer in Maroua

Christian Seignobos

Many researchers, mainly anthropologists, have emphasised the importance of sorghum beer in northern Cameroon1, in non-Muslim societies for whom celebrations and rituals were not possible without it. On the first markets, which opened between 1930 and 1960 in the 'pagan' regions, all the produce bartered or sold was used to make beer. As the millet used could not leave the family granaries for reasons of food security, it was acquired on these 'proto' market places, as was the related equipment. These markets thus began on a social basis that allowed different neighbourhoods, between which antagonisms existed, to meet and share a neutral and convivial space thanks to beer. This is still the role of the beer markets on the fringes of the large Muslim markets and the urban sarés for bilbil2. This social primacy of beer did not escape the attention of the administrative authorities, who, on the other hand, only wanted to retain its uncontrollable aspects and its excesses.

Millet beer: a century of administrative prohibition and tolerance

Millet beer has followed a pathway common to many other alcoholic beverages throughout the world. Initially reserved for the sphere of the sacred, long monopolised by the gerontocracy, it was gradually to be 'democratised', including in its manufacture, which was passed from men to women, and in its consumption. The transition to sale, which came later, was not without difficulties. The traditional authorities feared that this would put a threat on the millet stocks and the power of those who control them. There was also the prospect of women's economic autonomy, which was not very welcome, and finally, the risk of a deterioration in morals which the ancestors, censors of the conduct of the living, would not fail to sanction.

Subsequently, the administrators sought to veto this commercialisation, which the chiefdoms had had to endorse with varying degrees of grace.

Beer and the colonial and national administrations

The colonial administration was very early concerned about the harmful effects of millet beer on the natives, and its judgement about them in terms of 'improvidence' was partly based on the 'wastage' of millet for beer brewing, which was considered excessive. Faced with droughts and especially locust invasions in the 1930s, the colonial administration became obsessed with food security. In 1938, on the initiative Dietmann, chief of the Yagoua subdivision, a policy of reserve granaries was launched among the chiefs in order, on the one hand, to serve as a logistical stockpile to bring millet into an area of their command subject to famine, and to have a reserve of seeds on the other hand.

The administrative archives also denounce the endless conflicts after 'abundant libations of peepee', name given to millet beer in colonial French3 until about 1935. The references to beer in these same archives express both excess and imprecision, and the role of Muslim interpreters is suspected.

Investigations conducted in Maroua in April 1938 (N°1C, V33) at the request of the head of the political and administrative affairs department are revealing of this role. Entrusted to a Muslim, Oumara Bouba, they reveal that 'millet beer or mbal or better guia4 is consumed by people who don't care about religion. A single mbal drinker can empty 20 litres a day [...]'. Next comes the explanation of the manufacture not of mbal, but of another kind of beer:furdu.

The new national administration in the North, which was almost exclusively Muslim, did not change its opinion of millet beer. In the 1960s, after independence, the phenomenon of arge, a distilled alcohol even more controversial than beer, was added. The fight against every artisanal alcoholic beverages became stronger5.

The administration, being required to demonstrate its efficiency, will legislate and enact local regulations, which it will never have the means to apply, leaving entire sections of society de facto outside the law. In the last decade, almost every new sub-prefect, believing himself to be invested with a mission of public health, promulgated a ban on the distillation of arge or the brewing of millet beer, which resulted in broken canaries, arrested brewers and a widespread racket of these 'drinking establishments'6.

The administration has always oscillated between two postures: either banning beer on the grounds that it disrupts public order and wastes millet - even if it allows the payment of the head tax - or controlling it and collecting tax revenues from it. Only recently, in the markets on the outskirts of Maroua, the mayor of the rural commune had to give up collecting taxes (20% of revenues) from the women who brought their beer to the market. The energy expended to collect these taxes was too great, and attempts were always unsuccessful. Bello Bouba Maigari, Prime Minister from 1982 to 19837, was also credited with wanting to combat beer. This was largely exploited by the Rassemblement Démocratique du Peuple Camerounais, the ruling party, among the non-Muslim population.

The religious discourse

The Muslim 'scriptural' discourse and that of certain Protestant organisations (Adventists, Lutheran Brethren, etc.) prohibit millet beer. The Catholic missions, for their part, are of course fighting against alcohol abuse. However, a certain trend nevertheless presents millet, in its form of ball and beer, as possible substitutes for the bread and wine of the Lord's Supper within the framework of a more advanced inculturation of the Church (Jaouen, 1995). Faced with the practices of their flock, the missions as a whole relaxed their ban on beer and concentrated their vindictiveness on arge.

The missions are also called upon to make up for the past disciplines of these 'millet religions', which forbade the access of wives, potential brewers, to the family head's silo, the ultimate reserve. Today, this granary, which is also an altar, is only a place of storage, when it still exists. This deterioration of the old controls on millet is attributable, for those concerned, to the modern times and the impact of missions.

The role of health and public hygiene services

This role is recent and mainly concerns the 1990s. The intervention of these services covers the peak periods of the cholera epidemic coming from the border reservoirs of Chad. One of their corridors regularly reaches the Maroua region. The sanitary aspect is the new way in which the administration, in this case the communal ones, controls or prohibits beer.

Since L. Novellie (1963), the question has been ceaselessly asked: is sorghum beer a food or a drink? Nutritionists' answers tend to emphasise its nutritional qualities: calories, B vitamins, essential amino acids (lysine), mineral salts, etc. Some people wonder about the benefits of unfermented millet beer for young children, among the Tupuri for example. Wouldn't it be a food that protects their health? Nevertheless, the prevailing opinion in northern Cameroon is to stick to its formal condemnation.

At the beginning of the 1980s, millet beer, but also all beer, became a worrying public health problem, although the lack of information did not make it possible to 'accurately assess the extent of the problem'. The combination of religious, administrative and health service views makes millet beer a 'social scourge', which is confirmed by the 'developmentalist configuration' that is part of this guilt-inducing discourse.

The NGO and Development Discourse

Development has taken up and amplified the theme of food security, especially with the food shortages of 1973, 1983 and again recently from 1993 to 1998, with communal or community granaries.

The reports from Sodecoton and the newspaper Le paysan regularly stigmatise farmers who are still running around the beer markets instead of clearing their fields to be ready for the first rains8. The objective is twofold. On the one hand, it aims to fight against the loss of millet which, with the brewing of beer, is likely to be lacking at the time of the hunger gap and, on the other hand, to combat idleness. The ultras of the 'gender' movement NGOs develop other arguments. The culprits are men who alone drink beer. The women brewers, portrayed as victims, would be forced to do this work to ensure the only major transfer of money from men to women. This fusional brewer-client couple should therefore be destroyed and women should be given access to land so that they can finally generate real development (van Den Berg, 1977).

The millet beer, accused of being the cause of untimely deforestation, would hinder any prospect of sustainable development. Self-consumption of wood measured in three areas of the Far North9 would show that firewood used to brew beer could represent up to 36%. The data on this point, which is quite rare, should be added to the scientific debate, especially since, until now, the denunciation has been based on strictly preventive arguments, the relevance of which has yet to be demonstrated.

J. Koulandi (2000, p. 32) denounces the same misdeeds for the Tupuri country and, for M. Nanadoum (2001, p. 32), most of the wood marketed in N'Djaména is said to be used for the preparation of 'bili-bili This unanimity, backed up by numerous NGO reports, gives the matter a certainty. However, firewood is of interest to many other activities, as would those of the soya10 burners, tea merchants and many forms of catering. The denunciation of woody cover removals for brewery operations would probably hidden 'excessive truths' here.

A discordant voice, that of the traditional powers

As local relays of the central administration, the canton chiefs impose bans during a food shortage. Some try, for fiscal reasons and to curb excesses, to force women, in the foothills of the Mandara Mountains in particular, to take their beer to market and not to sell it at home, where unbalanced bartering takes place (calabashes of grain for calabashes of beer), which can lead to the dilapidation of some families' reserves. However, as a general rule, traditional powers, including Muslim ones, tolerate and even protect millet beer.

Under the regional chief, Mr. Cournarie, the brewing of beer was banned in 1938. The lamido Mouhamadou Sadjo himself interceded with the administration on behalf of the brewers and is credited with saying: "Without millet beer, Maroua would only be a small town"11. Even today, the lamido of Maroua, who knows how to count among the mountain migrants his most loyal supporters, never fails to intervene to protect beer districts from the racket of unscrupulous officials.

Millet beer in Maroua from 1972 to 2002: constants and changes

From 1971 to 1973, I undertook a study on millet beer in Maroua: production methods, types of beer, sales frameworks, economic impact... What is the situation today?

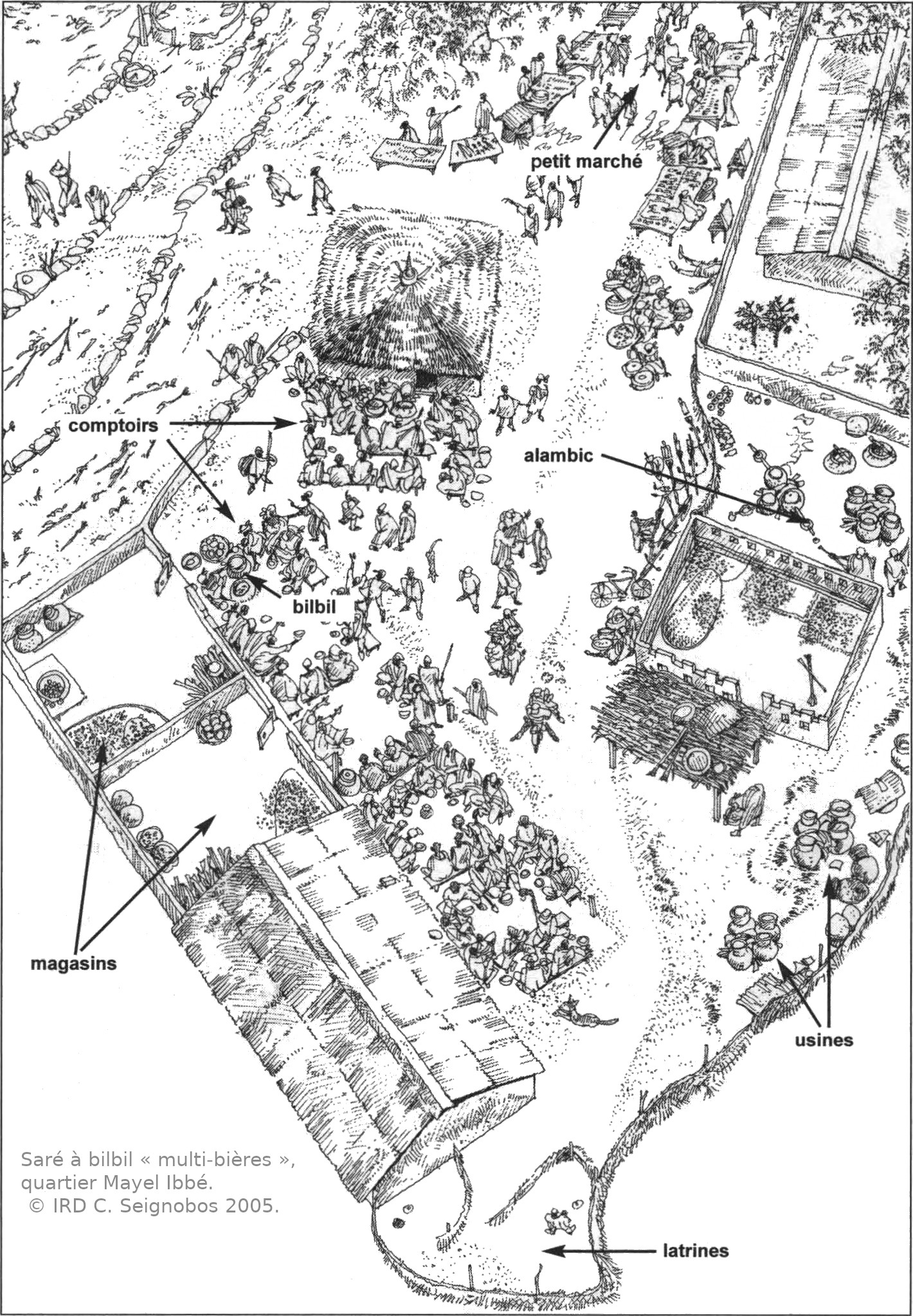

The districts that produce and sell beer have changed little. Pont vert (Domayo Pont), populated by Tupuri, Mundang and Ngambay, now called the "world market", became, together with the neighbouring district of Hardéo (Giziga and Chadian), the first beer "sector" after 1975. The second area, which did not yet exist in the early 1970s, is in Ouro Tchédé, where Giziga and Mofu live. The third zone would be Pitoaré, animated by the Mundang and the Gidar. Finally, the Palar, Doualaré, Fasaw, Mayel Ibbé (Figure 1) and Laïndé 'sectors', where the mountain people dominate, form a peripheral nebula. These beer "sectors" still operate to the rhythm of the local weekly markets; Pont Vert and Hardéo with the large market in Maroua on Mondays; Ouro Tchédé and Pitoare with that of Founangué on Sundays; Fasaw and Laïndé on Fridays...

In the 1970s, there were seven hundred women brewing beer (Seignobos, 1976). There were more than 700 'beer production units' in 2001 (Lopez, Muchnik, 2001, p. 152). However, with the spread of women's associations, the number of women brewers is expected to rise to 1,100-1,200.

Production methods and quantities brewed: little change

The equipment

The same types of jars are used for brewing and storing beer. These jars, ranging from 50 to 60 litres for the largest, always come from nearby production areas outside the town. The brewing of beer in metal pots, a technique brought by the Sara-Ngambay and which seemed to take precedence over the jars in the 1980s, was abandoned in 1989 after interventions by the municipal hygiene service. This method of brewing was accused of being detrimental to the health of consumers13.

OThe pasty ingredients in the bottoms of the canaries are mixed with the same stirring stick made from the nerves of the rônier palm tree or the stems of red sorghum from which the root tips have been preserved. To keep "the wine", we now use large aluminium pots (daaro), which are lighter and can be covered hermetically. However, it is the hardware for serving the beer that has most changed. Small pots for customers have only been maintained among the Tupuri and the Mundang. Civil servants and young people prefer to receive their beer in small plastic buckets. Nowadays, each customer has an individual calabash and some cabarets even offer wickerwork rings to put them on the ground. The calabashes collected after use are washed in the same basin and with the same water throughout the day. The hygiene discourse has only partially been passed on14...

The fuel

Faced with the scarcity of large wood, such as that provided by Balanites aegyptiaca, Prosopis africana and Anogeissus leiocarpus, the female brewers fell back on a second category consisting of Acacia nilotica, Acacia seyal, Dalbergia melanoxylon and Combretum spp.

The fire for brewing beer, taking place in the open air and not on the hearths of the houses, is considered profane. This allows the taking of dreaded essences such as >Combretum molle>, which would scare the women out of the house, but also essences that give off too much smoke when burnt, such as >Faidherbia albida >or >Sterculia setigera>.

The economic necessity of brewing beer has contributed to the breakdown of the last agrarian disciplines which, under cover of prohibitions, protected certain trees. In this sense, the removal of wood for beer production is not without consequences. In addition, the cooking time and the intensity of the fire are not always well controlled by the woman. If the degree of cooking is too low, the beer will suffer, so the woman will always be tempted to extend the cooking time.

The wood is also supplemented with dried dung collected by the children and bags of shavings are purchased from carpenters.

Sorghums and types of beer

The search for the best sorghum remains a primary concern for the women brewers. Bad millet" must not be used. For example, sorghum that has spent a long time in underground silos (Mindif region) and sorghum that has been weeded will not germinate well. New sorghums are not suitable either. Dry and not too freshly harvested sorghum is needed.

In order to get a constant quality of millet, the women make agreements with dealers who deliver to their homes and commit themselves to providing a good, unmixed product. They are bound by credits contracted with the women tenants.

The price of millet determines its purchase. Women start with early red sorghums (njigaari) before moving on to long-cycle ones, whose brewing capabilities are recognised, such as zlaraway, a mountain sorghum, and S35, a sorghum popularised by the Ira. After the March harvest of the transplanted sorghums, one of them, safraari15, is massively adopted. By then S35 had disappeared from the market and zlaraway, which germinates poorly in hot weather, is pushed aside. For the past two decades, the most consistent recipe has been based on one-third njigaari to two-thirds safraari. It should be noted that in Maroua, unlike Garoua, maize is not yet used in the preparation of beer.

The quantities of sorghum used are more or less constant in the neighbourhoods, in order to adapt to the same clientele on the one hand, and on the other hand, not to 'overtake the others' and thus not to be caught up by the principle of equality. Women brewers must limit themselves to a "reasonable success" vis-à-vis their community, for fear of arousing jealousies that would lead to hidden aggressions and ruin all their efforts.

The same rhythms are found in the dry season/rainy season, with a shift from two brews/week to one in the rainy season, with a smaller quantity of millet. Nevertheless, during this period, the number of brewers decreases and some women admit to making their biggest profits during this period.

The changes are mainly due to the quantities brewed in the large production units, with 100 to 150 cups (1 cup = about 1 kg) per woman, twice a week. In peripheral "sectors" (Makabay, Fasaw, Laïndé...), conversely, the quantities remain close to those of the rural areas. The average production in Maroua is said to be more than 100 litres of beer per production cycle for a 40 kg sorghum batch (Lopez, Muchnik, 2001, p. 153).

The same types of beers are found as in 1970. However, the valawa16, after making a breakthrough in the late 1970s, appreciated for its bitterness and reputation for warding off bad luck, is now on the decline. It remains on the northern fringes of the city where some mountain people still favour it. Furdu, a boiled beer consumed hot, only thrives during the rainy season. Older adults remain its most loyal customers. The proportion of women selling furdu (one in six in 1970) is said to have decreased further.

The making of bilbil

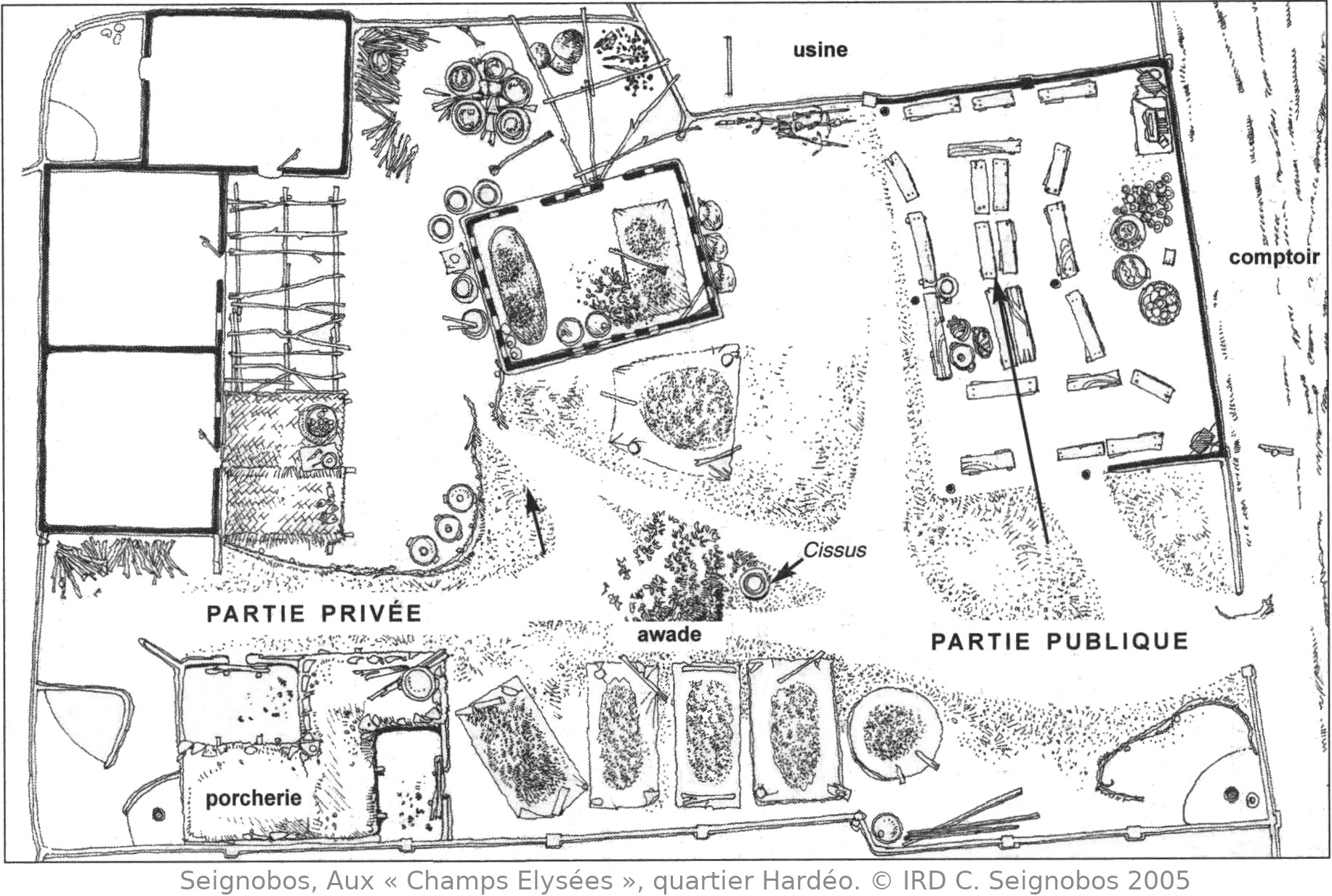

The sorghum grains are soaked twice for one day before being spread out on a plastic-covered mat in a hut (Drawing 2). The sorghum is left for two days, being sprinkled in the morning and evening before being enclosed in a bag for one night. Spread out in the sun, from eight hours to two days depending on the season, the germinated millet (awade17) is turned over by hand to detach the rootlets (gila ay nga awade: to break the neck of the germinated millet, in Giziga). This millet is then crushed in the mill. The "pushers" bring water (about ten 20-litre cans to forty cups of millet, for example) which is poured into large canaries. The awade flour, sometimes with fragments of Cissus quadrangulam18 from the bush, is then thrown into this water, and the mixture is turned until the suspended particles are removed (cake19).

After three hours, the flour has settled to the bottom. The supernatant liquid, about half of the total volume, called "la claire", is recovered and poured into the daaro. The decantation residue and the cake will form a slurry that is put into the jars of the "factory". These canaries have been previously washed with a decoction of Momordica charantia or with a decoction of neem leaves. The bitterness seems to be sought here. It is left on the fire for three hours. The liquid should then be filtered and left to settle with the "claire". The next day, the woman will carefully follow the acidification phase by regularly tasting her concoction.

She will then undertake the boiling and skimming of the wort ("la claire" + the filtrate), which will last four to five hours, in "factories" where the jars are stacked in groups of three, four or even twelve. Finally, she will gather her production and put in the equivalent of a glass of yeast, from the bottom of the vats of previous preparations. Fermentation will last about ten hours before consumption. During the whole process, "strangers" are not allowed always to approach the "factories"; those suspected of impurity, for having had sexual relations, may not touch the "factory".

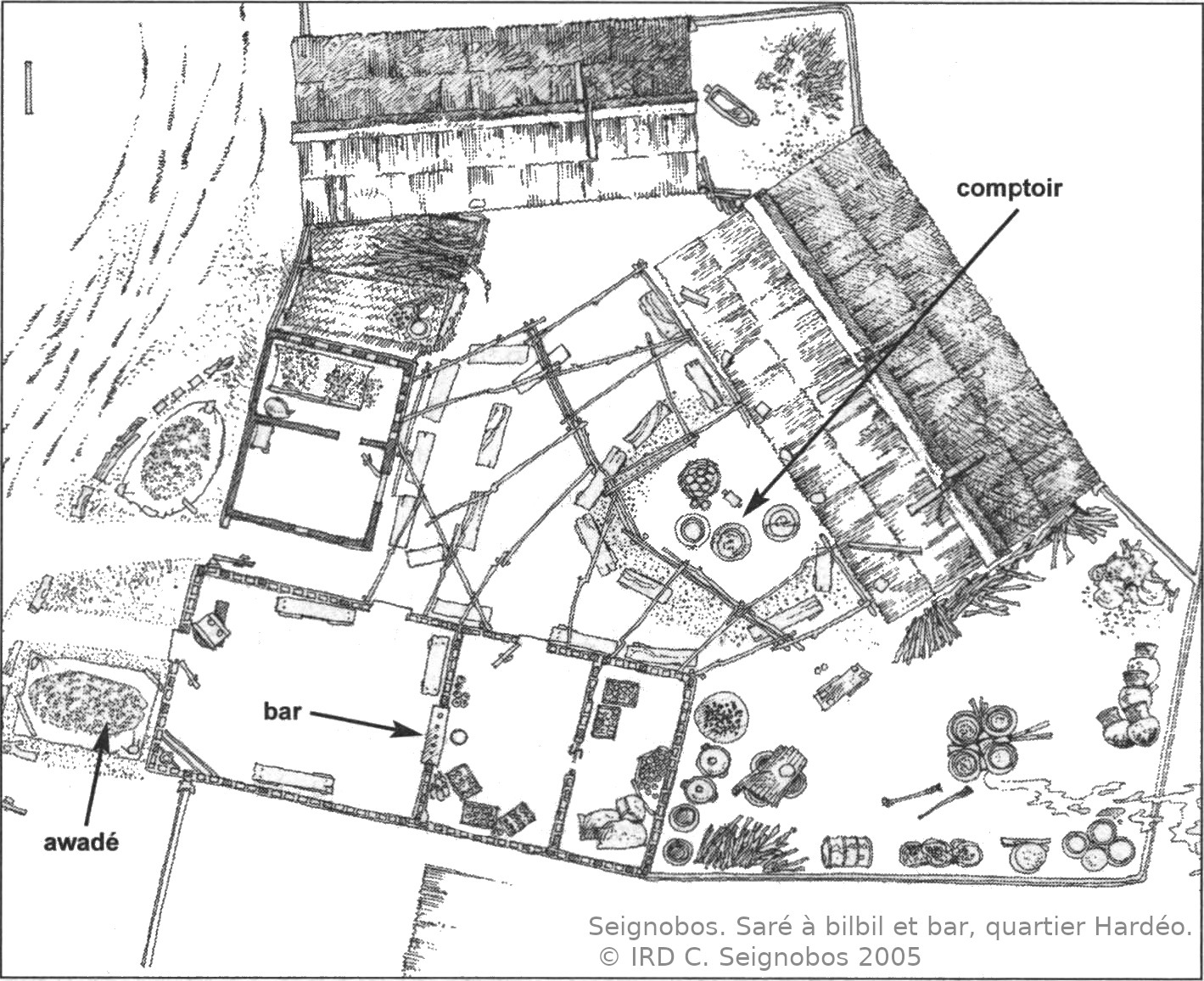

The brewing of beer may or may not be complemented by the distillation of arge, which would be a kind of technical extension of the large beer-making units. Some sarés for bilbil incorporate a very rudimentary still hidden at the back. All the by-products of beer: scum, dregs, lees, can be distilled. The arge is also a recycling means for distilling beer that has failed, that has not been sold properly or that has been left for more than twenty hours.

Cabarets and women innkeepers

Towards an urban integration of the saré for bilbil

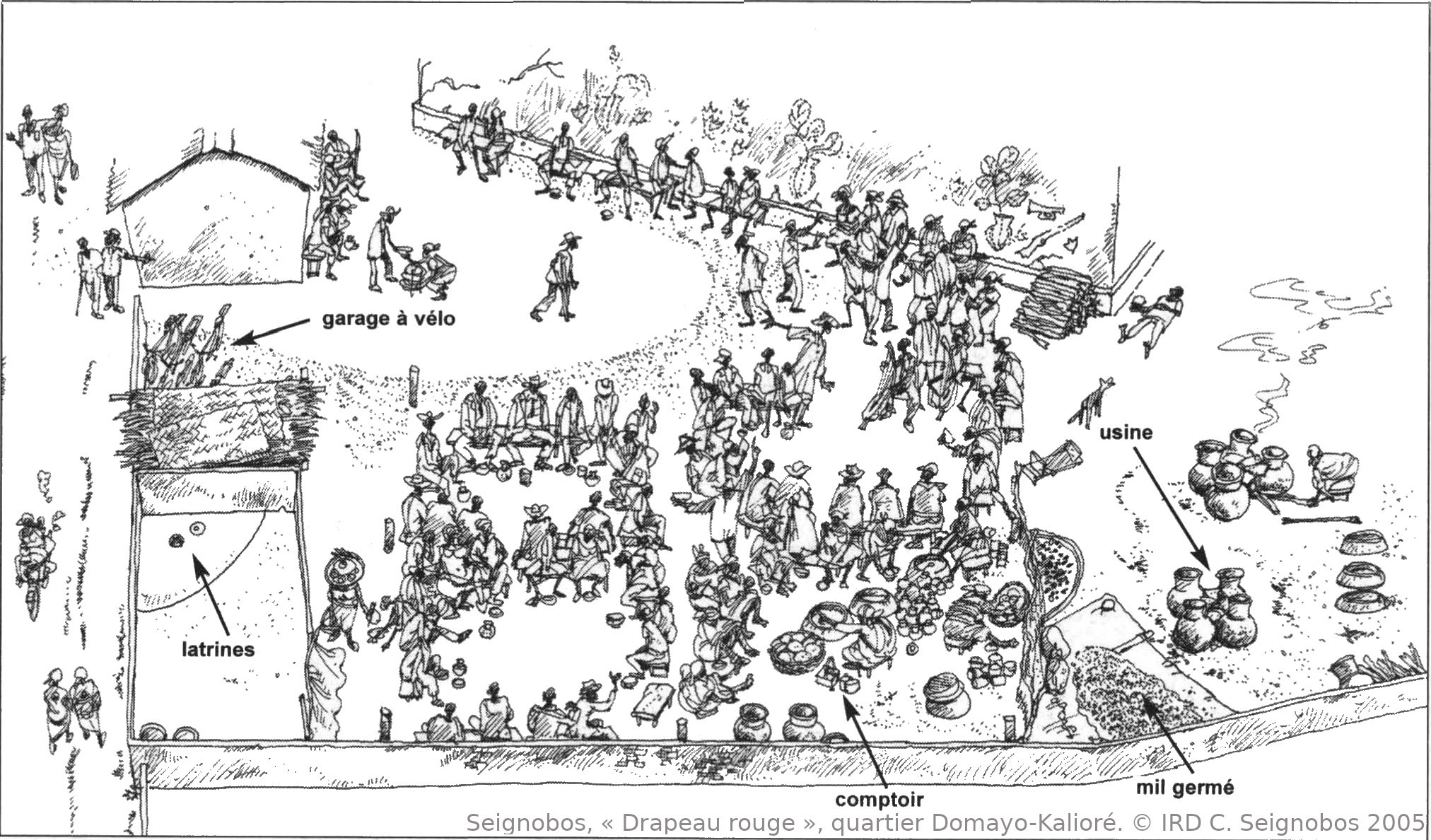

A working saré for bilbil is always signposted. A pile of dregs was placed nearby, and then at the end of the 1960s, "flags" were put up: a bottle with a stick pinching a coloured cardboard. Around 1980, the flags became more widespread and we evolved towards name signs. Today, we are often faced with real signs with, for example, in Hardéo: "Aux champs élysées, c'est la préférence, chez mama Hélène"..., or even reminders of current events: "Bakassi" (a conflict zone between Cameroon and Nigeria), G7... allusions to the cabaret owner's previous residences: "Base Congo", "Plateau de Jos", not forgetting the unmissable: "On-duty Pharmacy" and "Thirst Dispensary"...(Drawing 3)

The sarés for bilbil make up a kind of archipelago around the town, although there are still some enkystements, such as in Kaliaoré and Banguel, which have resisted being pushed to the margins by the Muslim town. These sarés are in clusters and must allow the passage of customers and visitors. There are accordingly ambulatories, kind of peripato where one is guaranteed to make expected encounters. The sarés for bilbil often change address as their owners rarely have a title deed20. It is hard to build a typology of all these cabarets. One passes imperceptibly from family-run sarés, sometimes real pockets of rurality, to more urban sarés, where the space is measured and where all the buildings, more or less coalesced, are solid.

The beer cabarets need space and each one is divided into a public and a private area (Drawing 2). The latter, protected by wickerwork palisades, frequently contains pigsties (several small, low buildings with earthen or tin roofs and flanked by courtyards) and sheepfolds. Between the private and public parts, geophytes and Cissus, apotropaic and also a prominent Calotropis procera, against thieves, are often noticed. Inside the beer section, two areas are quite distinct: the brewing area and the selling area, usually circumscribed by a large tin shed. The production area includes the "factories" and the decanting and cooling tanks, which are generally aligned. They often adjoin a small hut with openwork walls reserved for the germination of sorghum. A large open area is used to dry the germinated millet on tarpaulins.

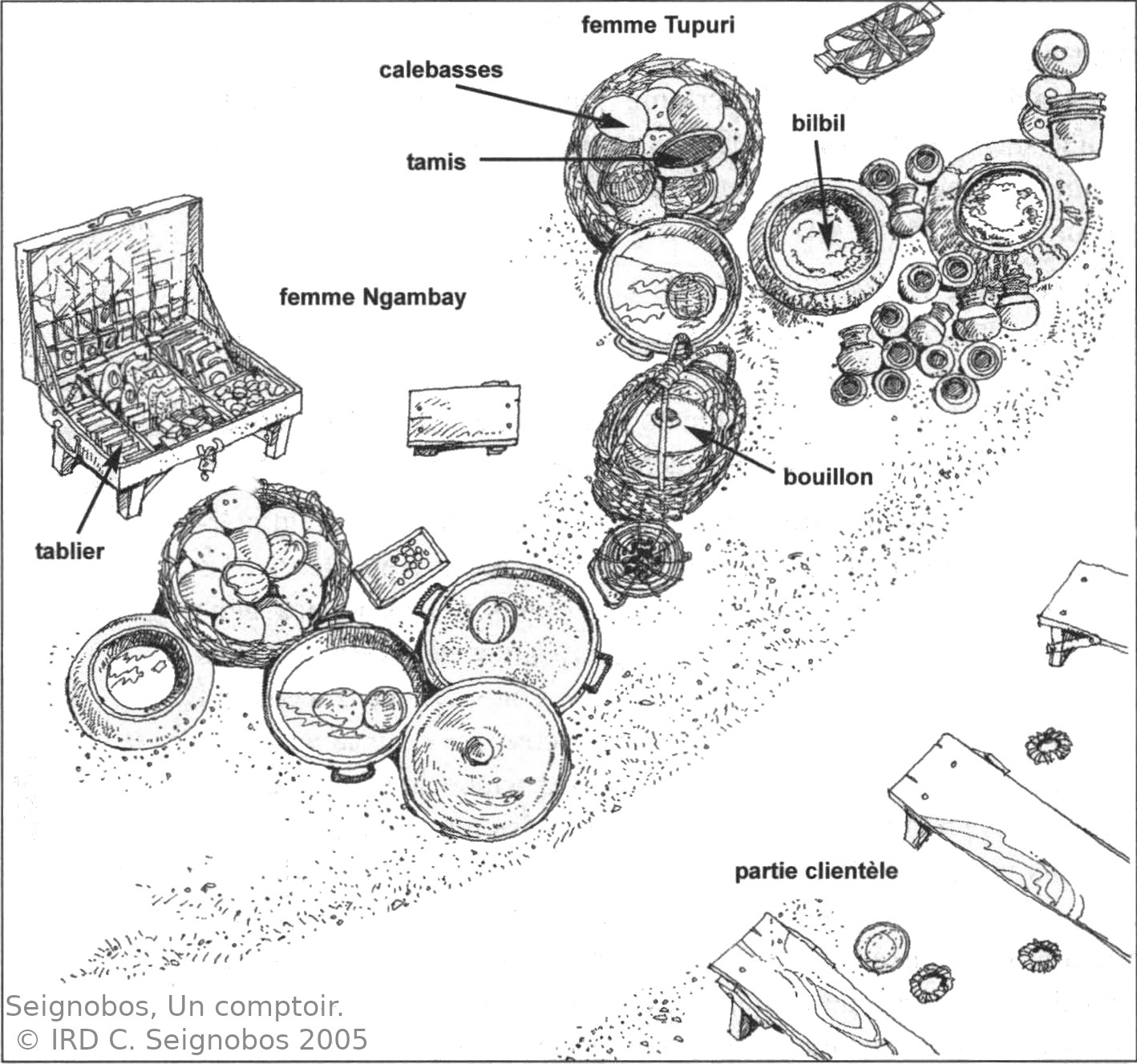

In the public area, there is also a place to store bicycles and also the indispensable latrines which, together with the pigsties, the beer waste and the "factories" in action, give off a pervasive smell that does not seem to bother anyone (drawings 2 and 3). Finally, there is the shed, with a whole set of school benches that have replaced the small village benches of the 1970s21. This is where the sound system and baffles are installed. Against the walls, next to the jars sunken into the ground, stands the woman, who sells her beer, earning this place the name "counter"22 (drawing 6).

We find the same types of women as thirty years ago: wives of pensioners, "compressed", small domestic staff, military personnel and also single women with families23. The same proportions are also found in the ethnic origin. Giziga women are the most strongly represented and Tupuri women have maintained their reputation as the best women brewers.

As brewing beer is a physical activity, only women between the ages of 25 and 45 are to be found. With their beer supply, still being fermented by the leavening, wedged between their legs, the matrons watch over the battery of calabashes, pots and buckets, their pot of "broth" kept on the fire on one side and, on the other, their display of cigarettes and colas... in an environment of interested relatives trying to force compassion and all this against a background of quivering customers who apostrophise each other.

The change is in fact expressed in the organisation. Women are grouped into 'societies' at the same point of sale. They co-opt each other and belong to different ethnic groups in order to attract and retain several customers. In the 'Banguel sous manguiers' cabaret, the owner is a Sara and makes 'bilbil nylon', a very light beer; another woman, a mofu, makes valawa, a third brews a gidar beer and serves it in special black-dyed calabashes; the last one, an Ngambay, offers a bilbil made of rice. These 'societies' usually consist of four women, and the one who owns or rents the saré is the boss. She sells her beer on market days, buys the wood and often the millet, which she passes on to her partners. The women share the equipment of the 'factories', usually on the basis of one 'factory' for two.

The manageress may remain at the 'counter', but in most cases she will give way to the one in the association who is recognised as being the most capable of magnetising the customer as metal filings, maximising profits and avoiding problems. The manageress provides the 'social capital' through her connections and the one who serves must show know-how. Indeed, for the same quantity of beer produced, the profits made can be very different depending on the situation of the cabaret, its clientele and the strategy adopted by the saleswoman. She must be a master at conceding the leeko, a small quantity offered to the customer to taste the beer before ordering, to the real affiliates, while skilfully excluding the others24. She has a duty to combine equal treatment of customers with respect for their ethnic or socio-professional background. Together with the owner, she creates the climate of trust that makes the quality and reputation of a saré for bilbil.

The women take turns in the production process and help the saleswoman, picking up the calabashes and sweeping the customer area. The environment remains very family-oriented, with the girls helping to serve and to transfer the various liquids. The children push the wood for the endless fires. These family incursions are all the more easy as the beer cabarets operate fundamentally during the day and the sale generally ends around 5 p.m.

A woman who regularly processes between 100 and 150 cups of millet twice a week can have an income of 120,000 CFA francs per month. She has control over her daily expenses, which was rarely the case in 1972. She is involved in tontines (10,000 F/week for Tupuri women), tontines often run by the manageress25. These women also lend small amounts to their best clients. They ensure that their daughters, by helping, finance their schooling. As for the boys, there are many "motoklando"26. The latter have been able to buy a second-hand Suzuki motorbike thanks to contributions from their brewing mothers, whom they in turn sometimes pay off and bail out following a series of sales failures.

When they did not help their co-workers, the women could go and sell doughnuts and broth in the neighbouring cabarets in return for their help. Some very enterprising women brewer sell beer and catering. This degree zero of the "informal sector" is built on modest pragmatism called "resourcefulness" here27.

Clientele and supervision

An increasingly mixed clientele

For those involved, the major change is a rejuvenation of the clientele: "Young people got into drinking". In the early 1970s, it was frowned upon for people under 25 to frequent the beer cabarets. Today, "resourceful", "motoklando", "lifeguards"28, but also students are there in large numbers.

Beyond the first circle of elderly people from the same group as the vendor and often more village than city dwellers, there is the circle of local affiliates and those who regularly come from nearby villages. During the rainy season, the latter demand beverages that replenish the body, such as furdu, when they leave for the fields or when they return. In the dry season, by contrast, after the sale of cotton, they will look for more refined and less nourishing beers.

There are a-ethnic circles of Francophones, composed of small civil servants - the akaawu - and Chadians. The patroness can also bring in free women to run her estaminet. These women always belong to her ethnic group and also act as waitresses. A room adjoining the cabaret can sometimes facilitate their business.

Finally, there is a kind of "passing" clientele (free-riders, yaroobe leeko), who seem to live only on beer. The well-stocked cabarets have 80 to 100 customers at any one time and see 600 to 700 people pass through in a day, sometimes more.

The animators

Some cabarets host musicians. Their instruments are Fulani or Hausa: geegeeru, a kind of viol with a small bow, or moolooru (garaaya in Hausa), a two- or three-string lute. Huge six-stringed harps (dilna) are also found in the Tupuri sarés and, elsewhere, those of smaller size, with one string less, of the highlanders.

The majority of these animators belonged, for a time, to groups of musicians who accompany the Hausa griots (bambaa'do) and learned to sing the praises of the mighties. Coming from haabe groups, they converted to Islam before returning to their home societies with this knowledge. All of them deploy a certain rhetorical efficiency and show themselves to be undisputed masters of the bar-room joke.

Hamadou Garaaya is a good representative. This Islamized Mofu learned the moolooru by working as a shepherd among the Fulani. Not only does he act, but he tells stories, mocks some, flatters others and claims to have inherited comedy. He himself has taken up the profession of griot. He mixes conventional speeches with more subtle remarks, sometimes borrowed from the mboo, poet-songwriters who censor morals among the Peuls, with a lot of innuendo and trans-ethnic symbolic references taken from fables and proverbs, in order to make fun of the local politicians. This histrionics has no equal when it comes to getting leeko. However, to supplement his income, he supplies fresh fish to a number of cabarets in which he performs.

These musicians are particularly active in traditionalist sarés, which are losing ground in the face of modernity expressed through the development of hi-fi equipment. The musical registers are therefore very variable. Ethnic music is slightly dominant and is played when a woman sells beer, thus underlining her presence with a sort of sound "flag" specific to her ethnic group. We also listen to music from the south, bikoutsi, makossa and even West Indian zouk brought back by the "rescuers".

The manageress can sort out her clientele on the basis of a musical selection. If the beer is very good, the patroness is congratulated by dancing to the rhythms of her ethnic group29.

The baba lawaale: an original form of supervision

The anarchic way in which the sarés for bilbil function is only apparent. They are controlled by baba lawaale (lit. Fathers of youth groups), derived from a Fulani mode of organisation. In Fulani villages, the baba lawaale set up mutual aid work for farmers who had fallen ill and also on the chiefs' land. He is responsible for redistributing donations in the village and for ensuring security. Chosen from among people of good character, he must be generous, have a good repartee and put the mockers on his side. This leader is designated by popular consensus (inkeeper women and customers) and this choice will be ratified by the chief.

In the case of the beer 'sectors', this is a respectable person who is familiar with the sarés for bilbil. His job is to judge conflicts within the cabarets, between the brewers, between the brewers and their customers and between the customers themselves. The 'offenders' pay in beer and colas, which the baba lawaale redistributes to his entourage30.

Twice a year, at the beginning of each season, the baba lawaale is responsible for checking prices in his area of operation, which may cover several districts. He checks the calabash used to measure the beer, called the "wine float" because it floats on the beer to be sold31. Accompanied by a delegation, he checks the unit of measure (seki'd gi wi mbal, in Giziga), which must be larger during the dry season, when millet is more abundant and cheaper. The baba lawaale often intervenes upon denunciation.

The baba lawaale can fine a female brewer who is too quarrelsome, who tries to upset her customers. He has the authority to have her production seized, or even to destroy the "factory" and can go as far as closing the estaminet. The woman brewer is then said to be "excommunicated". She can only reopen after having demonstrated her good faith by offering her first batch free of charge.

These men, who have a form of mandate from the population and therefore know many people, are a godsend and a challenge for the authorities. The lamido of Maroua, the mayors of rural and urban communes, and certain administrative officials seek to enlist their services.

Mana, baba lawaale of the Pont Vert and Hardéo 'sectors' from 1980 to 1999, controlled more than sixty cabarets for bilbil. The lamido confirmed him as baba lawaale and even made him a prominent member of his council (faada). Mana then had to take the lamido's share of the beer trade. The women, supported by the main affiliates of their cabarets, refused this zakkat (traditional tax) in the name of 'democracy which was already conjugated in their hearts'. In this matter, Mana gradually lost her credit with the women inkeepers. The refusal to legitimise a representation that would control the beer gardens was never seen as a formal opposition, as neither the women nor the affiliates had the capacity to do so. Rather, they seek to play the authorities off against each other to preserve their freedom.

Other authorities requested their assistance. The hygiene services of the town hall wanted to transform them into agents of the urban commune of Maroua. The baba lawaale had to accompany the hygiene agents who had made the cleanliness of these cabarets their hobbyhorse. They were then called "delegates"32. They withdrew when checks by these agents, accompanied by the police, turned into a racket. This was the case during cholera epidemics such as in 1996. The mayor's office took advantage of this to bring in the new liberation tax33 under the threat of banning beer. The barge makers had to suffer even more from the repression of the authorities. The suburbs of Maroua still remember the 'coup monté' by the hygiene services (1994-1995) who, in order to intervene, took the pretext of a rumour implicating certain women who had allegedly distilled human excrement. The police raids were brutal, followed by arrests of the "bouilleuses de cru" who had to pay a fine of 15,000 CFA francs and more. A delegation of baba lawaale34 and influential clients then went to lodge a complaint and denounce these excesses to the lamido.

In 2000-2001, raids by police and health officials also resulted in numerous arrests and fines. On each occasion, attempts were made to make people pay the final tax, about 10,000 CFA francs, and double that for 'foreigners'. For both campaigns, the population returned to complain to the lamido.

The representatives of political parties, notably the CPDM (Cameroon People's Democratic Movement), also tried to mobilise the baba lawaale under their banner. They were then called perje ('president' in Fulfulde). Some street-savvy women inkeepers, solicited by the same party, agreed to be activists, sometimes even as leaders of a CPDM sub-section (women's organisation).

Today, the baba lawaale posts are not all filled, firstly because their role is increasingly limited to traditionalist beer 'sectors' and secondly because they are retreating from new forms of policing. In the outskirts of Maroua, 'vigilance committees' were created around 1995, under the control of the traditional authorities, but with the approval of the gendarmerie brigade chiefs, to flush out the activities of 'coupeurs de route'. Since then, they have sought to provide a self-interested 'protection' in certain beer districts.

From ethnicity to a national society: apology of the saré for bilbil?

A place to drink, eat and talk

Each consumer evaluates the quality of a beer according to its physico-chemical and organoleptic characteristics (colour, consistency, taste, smell, alcohol content). These characteristics are linked to the grain used, to the brewers' know-how, but also to the degree of maturation or alteration of the beer at the very moment it is drunk35. The instability of the product leads customers to move from cabaret to cabaret in order to appreciate these different inflections.

The "wine" is the object of conversations and asides, and one reaches almost theological debates on the comparative use of millet in relation to the different categories of beer. One meets purists of bilbil, unconditional supporters of furdu, zealots of the new worts and fanatics of the old ways. One also regrets certain ways of drinking that are now in retreat, still under the blows of the hygienist discourse, such as drinking with two in the same calabash, the sloslo (lit. "two by two") of the Mofu, which demonstrated a shared friendship, sealed a meeting or reunion.

The Giziga, the majority ethnic group in the Maroua region, differentiate between numerous gustatory qualities for bilbil alone. Among those that should be avoided are pungent beer (mergezek), generally linked to poorly germinated sorghum; that qualified as korek, too acidic, or nde'dek, syrupy beer, poorly brewed due to a failing fire... Those who leave the saré for bilbil warn prospective customers of the poor quality of the beer with convenient expressions such as Vre zid le mung blam, 'The monkey has climbed to the top of the tamarind tree'.

When the beer has all the right qualities, the behaviour of the customers in the cabaret shows it immediately. Tart and bitter tastes are appreciated. The sweet liquid, not yet fully fermented, is given to the children as an appetiser on their return from school, while waiting for the evening meal.

Many ingredients can be added to the beer: millet flour (zlaraway among the Giziga and Mofu) or groundnut paste to break the acidity. The Bana, Jimi and Kapsiki continue to drink their beer with sesame oil. Some women also offer balls of tiger nut (earth almond or chufa) paste that are crushed in the beer.

Each set of sarees for bilbil looks like a market, a market of non-Muslims, perceived as a market of the poor. Old women sell groundnuts and onions. Young people wander around offering rags (gonjo), small rolled blinds (kasariyel), brooms, cigarettes, colas. There are also those who sell lekki 'bernde (medicine/heart), "to wash the body inside", "wet" alcohol from Nigeria that is mixed with beer. There are also traders of indigenous medicines (oils, barks, roots), which are said to be effective against stomach aches and to facilitate both the ingestion of beer and urination. Some others would prevent jaundice, which is rife in these contagious places, while others would protect against occult attacks... In addition to this, there are the little shoeshine boys, the manicures...

Near the beer halls, stalls of grilled meats (marara, soya) and breaded and spiced kebabs thrive, manned by men36. Inside the cabarets, women circulate with prepared dishes, broths of beef snouts, sheep heads, rooster heads, fish. Some of the dishes are intended for a precarious income, such as these broths made from chicken intestines and legs or beef tendons.

The food in the sarés for bilbil is increasingly varied: the ham-ham, a paste of Guinea sorrel with groundnuts, which can be mixed with broth, meatballs, wheat flour fritters (makala) or cowpea flour fritters (koosey) or even mashed potato (galaaji)... New dishes from the South have appeared such as kuki from corn, since 1996.

Cabarets have undergone a major change. In the 1970s, drinking was basically separated from eating. In 2000, this is no longer the case. For greater comfort, the drinker cuts out the acidity of the beer and pushes back the intoxication by multiplying the soy and broth snacks.

The food served in these cabarets is neither "street food" (street vendors selling soya, kebabs, dried meat (kiliisi), hard-boiled eggs, bread, doughnuts, "cakes" ...), nor "gargote" food where "braised" chicken and fish served with plantain bananas and potatoes dominate. Nor does it have anything to do with family consumption patterns, whether rural or urban, based on millet or rice balls and various companagium called "sauces". Beers as "ethnic signatures" have no equivalent in the foods brought and consumed in the cabarets.

There is a marked tropism in favour of variously prepared meats with the same flexible packaging of the products and their sale at all hours. Cabaret customers are looking for a break from family dishes for an urban style of food without real food extraversion, but less expensive than a drink served in the gargotes which is an industrial beer.

The birth of an opinion, the antechamber of a form of democracy

In 1970, in the sarés for bilbil that did not fit into a strict ethnic framework, there was silence and even unease. A mixture of apparent freedom and widespread surveillance characterised the Ahidjo period.

In 2000, the saré for beer became a privileged place for exchanges and public confrontation between people of different ethnic and socio-professional backgrounds. Since the introduction of the multi-party system in 1990, political expression has become increasingly free.

At this point, we can hardly escape the debate pro or against beer cabarets. They can be understood as places of futility, even deviation37, and some behaviour in a few cabarets would argue for this. A semblance of friendliness would in no way prevent the cascade of ordinary contempt from the Giziga towards the Mofu, from the Mundang towards the Giziga, from the patroness towards the labourer, from the wage earner towards the peasant, and from the ego-inflated contempt of the civil servant towards everyone else.

One is "entertained" there in the Pascalian sense of the term: one forgets. Some cabarets sometimes give the impression that the customers are nothing but a bunch of down-and-outs, "deflates", excommunicated people drowned in the middle of protean bands of fussy drinkers, themselves immersed in sordid calculations to get drunk at a lower price. Some, like Kabaré Zazou (Pont Vert district) for example, resemble "stunners" where dazed customers, lined up "in a row", face their beer bowls. Here we encounter groups of drinkers in the throes of dereliction, but isn't that typical of every plebeian 'boozer' in the world?

If the sarés for bilbil share the woes of all 'drinking establishments', they are also something else. They reflect more than half a century of spontaneous desegregation. Neutral, quasi-secular places, the cabarets see many ethnic groups rubbing shoulders. People can shout at each other without causing serious conflicts, and any outbursts are blamed on the beer. Millet beer is essential for inter-ethnic cohabitation on the fringes of the cities, as elsewhere on the pioneer fronts of the Benue plains.

The sarés for bilbil are, for the different social groups, spaces of 'shared sovereignty'. To frequent the bilbil cabarets of Maroua is to leave the ethnic group, where one does not choose anything, for a semi-freedom without any real instructions. The saré for bilbil is situated between an elective space and a 'native' space which is made evident by the very distribution of its customers.

A logic of compromise perpetually in action, always risky because of its fragility, always unsatisfactory because it is only partial, makes it possible to live with it because it is precisely the only way to get out of the ethnicity. This constant exercise of the otherness gives to the sarés for beer an irreplaceable role.

It is not only a question of getting out of ethnicity, but also of getting out of intergenerational inequalities, which are undoubtedly more marked within the same group. In these societies with highly compartmentalised age groups, the overwhelming domination of the elders leads to avoidance attitudes on the part of younger people, who are deprived of speech. The latter grow impatient, waiting to become, in turn, the beneficiaries of the system. In cabarets, exchanges between adults and young people are no longer codified. The older generation still plays at bullying the younger ones and gets paid for the beer, but it is no more than a mere game. Thanks to beer, the different generations are reknitting the threads of a social fabric that has been stretched by the intrusion of new religions, schooling and long stays in the cities of the South. Some moralists, far from seeing this old/young promiscuity as an ardent obligation, accuse the cabarets of destroying any notion of 'respect'.

Paradoxically, the bilbil cabarets are no less a sign of identity choices or support identity returns. To frequent them is to display an identity which is then specified by the choice of the type of beer. It means affirming one's awareness of belonging to the Catholic mission or, beyond that, to the Christian-pagan bloc, which is fundamentally different from the Fulani and the Islamised. It means opposing the moral superiority claimed by the Muslims of Maroua, the "city of Islam", to the rebellious vitality of the peripheral districts. In the context of authoritarian and closed societies, which seem to be condemned to a form of democratic inappetence, the sarés for bilbil offer havens for free speech. There is a search for greater equity, which cannot be equality until one has fully emerged from tribal societies where brothers and clan members are absolved in advance.

One detects a search for a common platform between neighbouring groups sharing the same doxa and the same rhetorical heritages. This is not so much an emerging civil society as an ethnic and social recomposition. We are witnessing groupings made up of Mundang, Tupuri, Masa and Gidar here; Mundang, Gidar and Giziga there; Mofu, Mafa, Mada, Zulgo elsewhere, with the bridges that are the schooled, salaried or civil servants.

A natural refuge for irregulars, for those called 'bad boys' by the colonial administrators in the 1930s, the sarés for bilbil are home to other marginals such as homosexuals. In Maroua, they are often Chadians, generally itinerant tea sellers (may saayi). They sometimes come to make a spectacle of themselves, adopting provocative postures. They remain under the protection of the women of the cabaret (saleswomen and regulars) and never expose themselves in public among the men.

The cabarets express, to very different degrees, social spaces of freedom and also of modernity. The latter is reflected in new behaviours: people come to read the newspaper, play the trifecta with a radio in their ear (the PMUC, Pari Mutuel Urbain Camerounais, has been present since 1996).

Beer loosens tongues, so that at the height of sales, the number of customers speaking French increases as they are no longer afraid to speak it badly. The sarés for bilbil are real language melting pots. Strictly speaking, there is no linguistic power issue. Bilkiire ("kitchen fulfuldé") is a lingua franca just like French, which does not give the impression of excluding certain groups from the speech community since several levels of language and expressions cohabit. In these sarés, people - the mountain people in particular - come to gather information about manners, behaviour or simple modes of dress. Here, they search for models that are inaccessible elsewhere.

In the course of these investigations, I met civil servants on leave, teachers, young writers, a film-maker... Those who occupy the stage are often teachers or school directors. We witnessed real religious and political "disputes". The local leaders of the main parties are mocked. The major insecurities and injustices are enumerated; the threat of "coupeurs de route" and "antigangs"38 are mentioned. Development issues are discussed by former Community Development and Irad staff39. Arguments are made, often rambling ones, but they are arguments nonetheless. Humour remains, here too, the subtle use of misfortune and, in the context of the sarés for bilbil, it makes the daily frustrations bearable. As in all the bars of the world, new answers to old questions are sought, but from all these conversations spores of democracy undeniably blow.

In 1972, I emphasised the importance of millet beer in Maroua as part of an informal survival economy. In 2002, the beer sarés, which are also present in the outskirts of the city, have been given a very different function in addition to their past role.

While they are still economically important for providing a living for a whole group of more or less floating populations and for helping to cushion the economic crisis of the 1980s, they have become socially requisite.

In these cabarets, set at the confluence of opposites, traditionalists and modernists, old and young, 'resourcefuls', and civil servants rub shoulders... Everyone finds there what they are looking for, a way of forgetting everyday life, a return to their identity, but also the construction of new knowledge, new demands... They allow them to exist socially, a fundamental preoccupation for these "compressed" [bureaucrats] of administrations, for these eternal mountain workers, for these "rescuers" who experience their return from the southern cities as a relegation.

The witch trial brought against millet beer, under the guise of an attack on morality, health and the environment, weighs little when compared to the essential role it plays in the creation of a form of citizenship.

BIBLIOGRAPHY

BARD V., MALKIN J.E., 1982 — La production de bière en Afrique. Institut santé et développement.

DJANAN D., 2002 — Contribution à l’étude du fonctionnement des petites entreprises agroalimentaires : cas des unités artisanales de transformation de sorgho en bière locale, "bili-bili", à Moundou au Tchad. Cnearc, Prasac, Montpellier.

EGUCHI P.K., 1975 — Beer drinking and festivals among the Hide. Kyoto University African studies IX : 69-90.

GARINE E., 1995 — Le mil et la bière. Le système agraire des Duupa du massif de Poli (Nord-Cameroun). Thèse de doctorat de l’univ. de Paris X-Nanterre. multigr.

GAUTIER D., TEBAYA O., 2001 — Sauver la brousse ou boire du bilbil. La lettre des savanes, Prasac : 6.

JAOUEN R., 1995 — L’Eucharistie du mil. Langages d’un peuple, expression de la foi. Paris, Karthala.

KOULANDI J., 1999 — Le bili-bili et la « libération » de la femme tupuri (idées et réflexions pour un débat constructif sur l’avenir de la communauté tupuri du Tchad et du Cameroun). Garoua.

LOPEZ E., MUCHNIK J., 2001 — Des systèmes agroalimentaires dans la ville ? Le cas de Maroua au Nord-Cameroun. Etud. Rech. Syst. Agraires Dév. (32) : 145-163.

NANADOUM M., 2001 — La « bili-bil », bière traditionnelle tchadienne : études technologiques et microbiologiques. Thèse de doctorat de l’Institut national agronomique de Paris-Grignon.

NOVELLIE L., 1963 — Bantou beer: food or beverage? Food ind. S. Afr. 16, 28 p.

NOYE D., 1989 — Dictionnaire foulfouldé-français, dialecte peul du Diamaré, Nord-Cameroun.Paris, P. Geuthner.

PERROIS L., DIEU M., 1990 — « Culture matérielle chez les Koma-Gimbe des monts Alantika (Nord-Cameroun) ; les gens de la bière de mil », In Barreteau D., Tourneux H. éd. : Relations interethniques et culture matérielle dans le bassin du lac Tchad. Colloque Mega-Tchad (11-12 sept. 1986), Orstom, Paris : 175-182.

SEIGNOBOS C, 1976 — « La bière de mil dans le Nord-Cameroun : un phénomène de miniéconomie ». In Recherches sur l’approvisionnement des villes et la croissance urbaine dans les pays tropicaux. Mémoire du Ceget, CNRS : 1-39.

SEIGNOBOS C, TOURNEUX H., 2002 — Le Nord-Cameroun à travers ses mots. Dictionnaire de termes anciens et modernes. Paris, Karthala-IRD.

Van BEEK W.E.A., 1978 — Bierbrouwers in de bergen. De kapsiki en Higi van Noord-Kameroen en Nordoost Nigeria. Icau Medeling, Utrecht n° 12. Instituut voor culturele Anthropologie.

Van Den BERG A., 1997 — Land right marriage left : women management of insecurity in north Cameroon. CNWS publication, Leiden.

SUMMARY

Between 1972 and 2002, the technology of sorghum beer production in Maroua did not change and the quantities brewed changed very little. Sorghum beer still plays a part in the economy of survival in the city. However, it has today many other functions as well. In the « saré à bilbil », one does not only come for drinking, but also to eat, talk, and debate. Despite the moralizing discourses against them, beer bars are becoming true havens of free speech where a new form of citizenship is being constructed.

Keywords : sorghum beer, bars, bar tenders, citizenship, Maroua, Northern Cameroon

NOTES

1. Beer drinking and festivals among the Hide de P. Eguchi, 1975 ; Bier brouwers in de bergen. De kapsiki en Higi de W.E.A. van Beek, 1978 ; Culture matérielle chez les Koma-Gimbe des monts Alantika : les gens de la bière de mil de L. Perrois et M. Dieu, 1990 ; Le mil et la bière. Le système agraire des Duupa du massif de Poli de E. Garine, 1995 ; Le bili-bili" et la "libération" de la femme tupuri de J. Koulandi, 1999...

2. The term 'saré' has become so familiar in local French that it is often used to refer to all types of 'concessions' in North Cameroon.

3. Used at the same time in Chad, this term comes from a Banda dialect, Central African Republic (Seignobos, Tourneux, 2002, p. 223).

4. Mbal is a loan from Foulfouldé to giziga mbazla, while giya is a much older loan from kanuri.

5. We will only mention the circular n°13 cf/INT/APA/2 to the prefects, sub-prefects and heads of district.

« Purpose: Creation of files for beverage licenses, clandestine openings of beverage outlets, local manufacture of alcoholic beverages.

The directive on political and administrative affairs of 13 August 1962, signed by the Secretary of State for the Interior, Y.M. Lamine, recalls the decree of 24 May 1931 followed by subsequent amending decrees, and forcefully reiterates the administration's position [...]. You will also ensure that the local manufacture of alcoholic beverages such as "arki", a real alcohol, harmful to health and social welfare, ceases. To this end, I ask you [...] to have the village or group chiefs inform you of the various manufacturers of this poison and to invite them to cease their activity without delay. If they persist, you will have to take them to court, in accordance with the regulations in force [...]. You will not fail to seize and destroy all objects used in the manufacture of arki".

6. For the different statements in the Maroua archives about the prohibition of beer and arge, we refer to Seignobos, 1976.

7. He later became president of the UNDP (National Union for Democracy and Progress), the main opposition party in the north with a strong Muslim background.

8. "How many crops are not tended in time, weeded, hoeed. Yet the number of people visiting the markets, especially the bili bili markets, has never been so high. And you say poverty? [...]. As long as our planters [...] indulge in their favourite pastime: market, gambling, bili bili [...], 'poverty' will reign supreme in the North Cameroon countryside. Editorial Le Paysan nouveau, n°4, June 2000.

9. Balaza with a very large Muslim majority, Mowo and Gadas with non-Muslim groups (see Gautier, Tebaya, 2001, p. 6).

10. From hausa [sooyàa], to grill/grilled meat.

11. This sentence is also attributed to other Lamibe of Maroua, such as Lamido Yaya (1943-1959).

12. This notion of socialisation through beer has not been entirely dismissed, and D. Gautier and O. Tebaya (op. cit., p. 6) ask: 'To what extent should nature bear the cost of this social bond?' Tebaya (op. cit., p. 6)

13. These 200 litre kegs provide a better reaction to fire. They do not break like pottery and allow larger quantities of beer to be produced. They are still used in Chad. However, those involved agree that this cask bilbil is of poorer taste quality.

14. Hygiene officers do not monitor the manufacturing process, nor the proximity of the 'factories' to latrines, nor the state of the uncovered canaries in which the beer is stored.

15. These sorghums are mainly Sorghum caudatum, S. durra or Durra caudatum.

16. A beer from the Hurzo of the Mémé region, it is brewed with zlaraway sorghum in which caïlcédrat bast is macerated. It has spread to the foothills of the Mandara Mountains as far as Maroua. It is responsible for the death of a large number of caïlcédrats, including in Maroua itself.

17. Awade, to designate the sprouted sorghum, comes from aawdi, seed, in Fulfulde. More rarely, puunaandi, the real name for sprouted millet, is used, again in Fulfulde.

18. These Cissus would seem to have the same role as the gelled decoction obtained from the bast of Grewia mollis, added during the decantation process. This decoction, used in Chad, would improve the flocculation of suspended matter (Nanadoum, 2001).

19. Cake comes from sakaago (fulfulde), to filter a liquid. The dregs remain in the filter or solid elements that float up.

20. Nevertheless, there are still some bilbil cabarets, such as 'Drapeau rouge' in Kaliaoré, owned by a Tupuri ex-combatant and where we had already investigated in 1972 (Drawing 3).

21. The owner of the sarés for bilbil rents independently the brewing and drying area (500 F CFA/day) and the sales point under the shed (250 F CFA/day).

22. There are a few cabarets that straddle both bilbil and industrial beer productions. They offer a small permanent space called "a bar". They try to keep up with a clientele of wage earners who maintain a certain purchasing power at the beginning of the month and who consume the products of Cameroonian breweries. But they inevitably switch to the bilbil-beer even before the middle of the month.

23. A few men may engage in these activities, but it is women who market their produce. They are mostly single men.

24. Customers who have consumed a lot in a cabaret ask for a little extra free beer before they leave, called 'prior notice to leave'.

25. Several manageress can organise 'pari-sales' (from pare, a tontine in Arabic). These sales methods, originating in Chad, have been developing in Maroua since the mid-1990s. These are kermesses where people can come as a couple and by invitation. The income is based on the sale of beverages (not only millet beer) whose prices are multiplied by two or three. These 'pari-sales' are for revenge between groups of women.

26. Also called "clandestines" because they have a motorbike taxi, personal or not, and do not pay a licence.

27. For J. Koulandi (1999, p. 34), a woman who brews beer is 'at the forefront of family resourcefulness'. It is the first economic technique other than the fields working that women have mastered. The emancipation of the Tupuri woman, thanks to beer, dates from the 1950s.

28. The term 'sauveteur' is derived from 'sauvette' in 'vente à la sauvette' [hawking in the street. A 'sauveteur' is a kind of peddler]. It was coined in the towns of southern Cameroon at the end of the 1980s and refers to young mountain people from the Mandara Mountains who practised a number of petty businness. They were to return en masse to the north after the economic crisis of the 1980s and 1990s (Seignobos, Tourneux, 2002, p. 248).

29. The music of the cawal giziga, the mofu and mafa flutes... still show strong ethnic resilience in urban areas.

30. The person who has spent the most money in a drinking circle, whilst also maintaining a good level of conversation and respecting the rules of decorum, may be called 'Baba lawaale' to honour him.

31. The beer trade follows the same rules as the sale of millet, the price remains constant and only the container varies.

32. The mayor of Maroua is not elected, he has been appointed since 1996 and is a 'government delegate'.

33. The flat-rate tax or capitation tax was abolished by the July 1995 Finance Act and replaced by a 'withholding tax'. This tax, which is proportional, is levied at different rates on the profits of economic activities. The bilbil sellers would belong to category A (low income) and the tax would be less than 12,000 CFA francs. But do they own a licensed beverage outlet? Tax rolls were to be established by the communes, but they have not yet been created in Maroua. The urban and especially rural communes of Maroua, deprived of the capitation tax, lack resources and are trying, in a roundabout way, to revert to a 'flat' levy. The women brewers are particularly worried about this chaotic and unpredictable tax system.

34. The baba lawaale of the arge 'clubs' are not the same as those of the sarés for bilbil, but they perform identical functions.

35. The yeasts are still active when the beer is served to the consumer. A few hours later, lactic acid fermentation replaces alcoholic fermentation and the beverage becomes sour. Those who are professionally knowledgeable about millet beer look for the bilbil at the moment it reaches its peak in alcoholic fermentation.

36. The soya burners are generally fincoo'be boys called 'grapplers' (Noye, 1989, p. 118). They belong to the lowest category of butcher boys, mostly mofu, and earn their wages with the meat they remove from the carcasses for grilling and selling.

37. The accusation that arge is a 'noxious and toxic beverage', as opposed to millet beer, which is an 'integrating and healthy beverage', cannot be levelled at arge without risk of reiterating the Manicheanism of the administration and development projects regarding bilbil. The fact remains that the arge corresponds to a radical group of drinkers who claim to be such. For them, beer, which is 3.5°, is not strong enough. They willingly adopt provocative postures, claiming to be 'the wives of the arge who does with them what it wants'. Thus, the excesses triggered by distilled alcohol have been instrumental in mobilising local elites for a decade in moralising campaigns through development committees or associations.

38. Specially trained gendarmerie units, whose members are often in unmarked uniforms on the spot, fight against road cutter gangs.

39. D. Djanan (2002, p. 91) says the same regarding the beer cabarets in Moundou, Chad.