Your search results [1 article]

Australia and the beer of the very beginnings.

The official history of the brewery in Australia states : « Beer was first introduced Down Under via the HMS Endeavour, when Captain James Cook landed at what we now know as Botany Bay in 1770. Aboard ship it was a means of preserving drinking water to stave off scurvy. »[1]

Captain James Cook did indeed test several fermented beverages, mainly made from grain and molasses, to prevent scurvy during his long, non-stop high seas voyages. However, in 1770, this technique had not yet been tested on a systematic basis by him. Scurvy killed 30 out of 85 sailors during his first expedition. When James Cook reached terra australis in 1770, sweet wort (an infusion of malt) was not yet used on board. It was used during his voyage around the South Pole between July 1772 and July 1774. He returned with his entire crew in good health, a feat at the time that earned him the highest award from the Royal Society of London on 30 November 1776, which commissioned his second voyage.

In his time, ships always carried fresh food, preserved food and alcohol. It is also known that scurvy inevitably sets in among the crews after an average of 68 days without fresh food[2]. The technique Cook tested was different: he had beer brewed on board, i.e. he made an anti-scurvy beverage on board without depending on ports of call. Aided by MacBride's experiments in England, Cook suspected that beer and fermented products in general were the miracle cure for scurvy.

Of course, James Cook did not set up a brewery in Australia. He was an explorer, not a coloniser. James Cook is not the "discoverer" of Australia either. The Dutchman Willem Janszoon passes within sight of the Cape York in 1606, and goes ashore on 26 February 1606 at the mouth of the Pennefather River (Weipa at Cape York). Later that year, the Spanish explorer Luís Vaz de Torres sails among the islands of the Torres Strait. So initially, a competition between Spanish and Dutch, the two major colonial powers in this part of the world in the 17th century. Neither sought to occupy the terra australis.

Between these first explorations of terra australis and that of James Cook a century and a half later, shipwrecks, mutinies and voluntary exile brought to this continent men of all categories, mostly sailors. Did they brew beer on Australian soil? Before contact, Australian starchy plants existed: undomesticated local millets, and among the domesticated plants two species of yam (Dioscorea hastifolia and Dioscorea transversa) and a taro (Colocasia esculenta) originating in the Far East. The Australian aborigines could therefore technically brew beer. Did they?

They made and drank fermented beverages from sap, fruit, sweet berries or wild honey[3]. Recent research has lifted a corner of the veil. It concerns regions at opposite ends of this continent: Tasmania in the south, the Western Territories, the Northern Territory, and the Torres Strait at its northernmost tip.

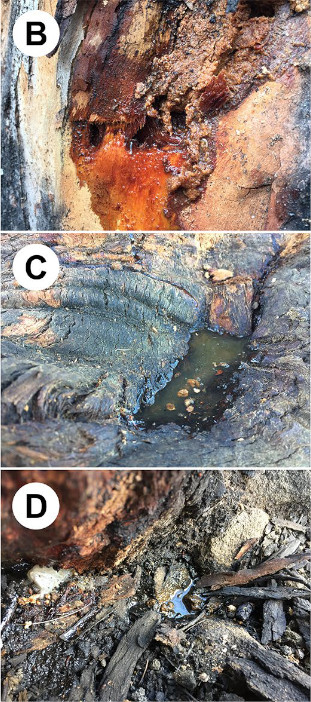

In Tasmania, the Aborigines collected and fermented the sap of the Eucalyptus gunnii tree to prepare an alcoholic beverage called way-a-linah long before the first contact with Europeans. Eucalyptus gunnii is a tree endemic to Tasmania, particularly resistant to the cold[4]. This endurance is explained by the nature and high concentration of the sugars that make up the sap. Glucose, fructose and maltose are the main sugars in the sap of E. gunnii, a composition close to that of honey (Varela et al. 2020). The aborigines dug the trunk with a sharp stone to make a cavity into which the sap flowed naturally, closed it with a flat stone to avoid visits from animals and insects. The yeasts present spontaneously converted the sweet exudate into mead, without human intervention[5]. The sugar concentration ranges from traces to several grams per litre. The final alcohol density is between 0 and 6%/vol.

When the botanist Sir Joseph Dalton Hooker described Eucalyptus gunnii in 1844, it was already known locally as the cider tree or cider gum. This is an indication of an ancient usage among the indigenous populations who had equated the tree with a characteristic reminiscent of the Canadian maple. For the same reasons, the Amerindians of the North had associated the maple trees with the production of sap that could be transformed into an alcoholic beverage.

In western Australia, Aborigines made a fermented beverage called mangaitch from the cones of the Banksia tree, a genus of trees endemic to the entire Australian coastline (80 species). The Aborigines dug a trench near a swamp and then covered the trench with a boat-shaped vessel made from tea tree bark, the coolamon[6]. This container was filled with water and Banksia cones macerated to obtain a sugar-rich solution, which was then left to ferment for several days (Brady Maggie, 2008).

In the northern territories, the aborigines prepared another kind of fermented beverage, kambuda, from the seeds of the fruits of the Pandanus, a pseudo-palm tree. The genus Pandanus includes more than 750 species spread over Oceania, Pacific and Indian Oceans[7]. It probably arrived in northern Australia via New Guinea. Kambuda can be likened to a beer. The starchy seeds are used to make it. These seeds are roasted and then ground to extract the starchy content, as one would do with cereal grains. The resulting paste is soaked for several days in water in which it ferments spontaneously after acidification. This starchy paste can also be dried and stored for several months before being used to brew kambuda beer. This aboriginal beer has been reported from the Borroloola region of northern Australia (Brady Maggie, 2008).

|

|

|

| Flowers of Banksia paludosa subsp. astrolux, Australia | Pandanus tectorius, Growth habit in Australia (Photo Murray Fagg) | Pandanus utilis fruit |

Early expeditions and settlements along the Murray River between Adelaide and King George Sound around 1840 describe the use of the mealy gum-scrub roots (Eucalyptus fasciculosa) : "In addition to the value of the gum-scrub to the native, as a source from whence to obtain his supply of water, it is equally important to him as affording an article of food, when his other resources have failed. To procure this, the lateral roots are still made use of, but the smaller ones generally are selected, such as vary in diameter from an inch downwards. The roots being dug up, the bark is peeled off and roasted crisp in hot ashes; it is then pounded between two stones, and has a pleasant farinaceous taste, strongly resembling that of malt. I have often seen the natives eating this, and have frequently eaten it myself in small quantities." (Grey 1845, 250). Brewing beer was possible, although the European reports do not mention it.

Paul Siltoe had already pointed out in 1983 the diversity of food plants in Papua New Guinea and the richness of the associated techniques. The karuka (Pandanus julianettii, also known as karuka nut and Pandanus nut) is an important food resource. The seeds contain between 28-33 g of starch and 5 g of sugars. More nutritious than coconuts, they are dried and used to make flours and brew beer. A special method is to leave the seeds in stagnant water for several weeks, which slowly breaks down the seed coat and saccharifies the starch, followed by anaerobic alcoholic fermentation.

We note two important facts about the history of traditional fermented beverages in ancient terra australis: 1) Far from ignoring fermented beverages, the peoples who have lived on this continent for 30,000 years made and drank wines from fruits or berries, and meads from wild honey or sap; 2) a beer made from Pandanus seeds was brewed in the north of the continent, probably in connection with the peoples of Papua New Guinea. When did this technique appear on Australian soil? Before 1770 for sure. At what time excactly is unknown.

Another Aboriginal technique is correlated with the ancient brewing of beer in Australia. Aborigines make bread by crushing seeds from a native millet (Panicum decompositum and Panicum australianse), a grass, spinifex (Triodia) or acacia (Wattleseed). Dried and ground into flour, these seeds are used to make bread baked in dug out ovens, the bush bread that European settlers adopted before introducing their own grains. The entire history of brewing around the world tells us that bread and beer are twin food products. Whether in the primitive form of unleavened bread/breadcrumbs, or the more advanced form of leavened bread, baking and brewing are based on complementary food techniques: starch extraction, milling, baking, fermentation. Some early protohistoric brewing techniques involved crumbling bread into a liquid and allowing it to ferment.

In the absence of archaeological research in Australia into the material life of ancient Aboriginal peoples, it is difficult to say more. As on other continents, it is likely that fermented beverages on terra australis have a very ancient history, a complex evolution made up of local inventions, borrowings and adaptations, a social role differentiated according to cultural regions, many centuries before the first contacts with Europeans.

An hint is given by the presence in the north of an aboriginal tradition that seems to be richer than elsewhere. The proximity of Papua New Guinea, the Moluccas, Timor, Java and Indonesia has had an impact on technical and cultural exchanges or the spread of food plants. The inhabitants of the Torres Strait islands produce a fermented and then distilled beverage, tuba, from the buds of coconut palms. This technique is based on knowledge acquired from the people of South East Asia. It spread throughout the Pacific, including the northern coast of Australia, centuries before Europeans arrived in that part of the world. Brady and McGrath have studied the routes by which tuba, both coconut wine and distilled alcohol, spread across the Pacific. This fermented beverage is very old, although its chronology cannot be ascertained because it is often confused in ancient Indian, Chinese or Javanese texts with palm wine. Nevertheless, they conclude that the technique of distilling tuba reached the Torres Strait islands in the early 18th century, brought by fishermen from the Makassar region of South Sulawesi. Prior to 1720, there is no evidence of distillation in the Torres Strait Islands, let alone on Australian soil (Brady, McGrath 2020, 315).

Tuba was made from sap flowing from a cut in the Cocos nucifera L. fruiting bud, which was collected and fermented for several days (Brady, McGrath, 2010). The addition of Ceriops tagal bark, a tannic, colouring and yeast-bearing agent called tangog in the Philippines, controls the fermentation. The process does not stop there. The distillation technique was learned by the aborigines of the Torres Strait around 1720. Once fermented (4-5 days) the coconut wine is filtered to separate the sediments (yeasts + coagulated proteins). The operation (fermentation + decantation + filtration) can be repeated once or twice. Each time, the alcohol content increases, which is the aim of the distillation process.

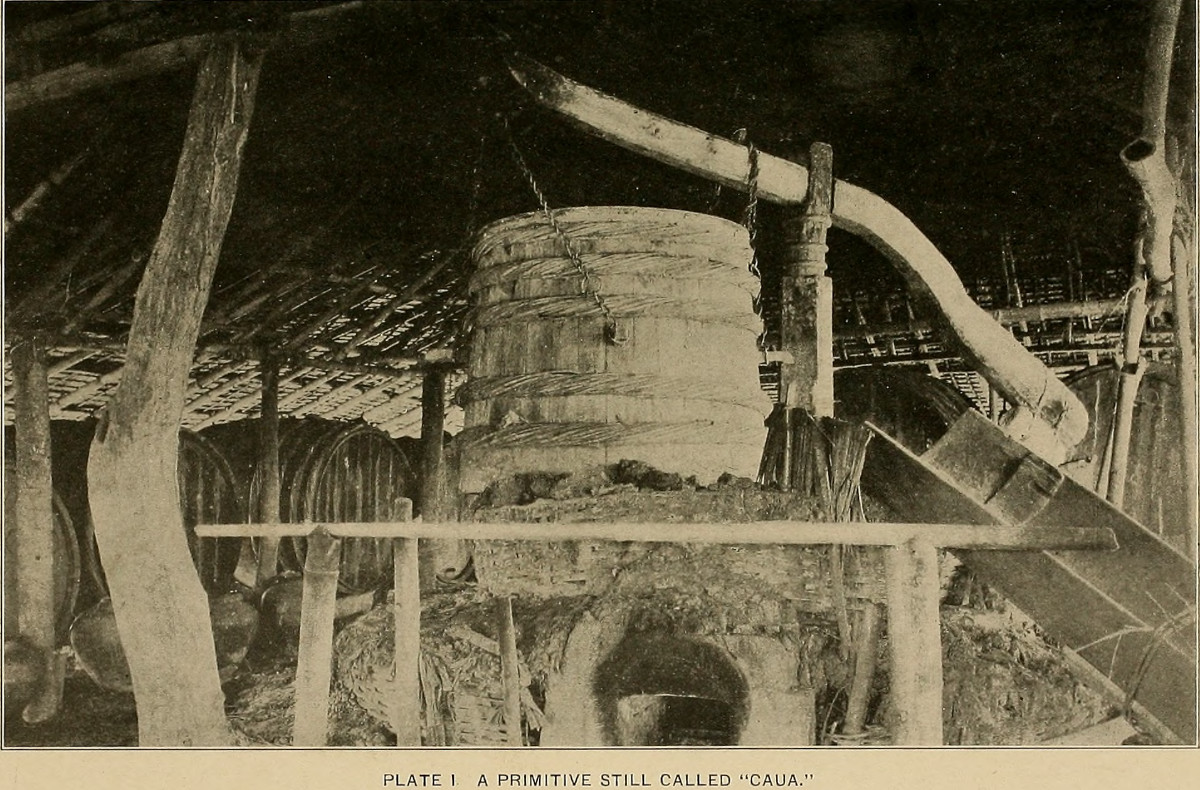

A still made of bamboo tubes placed on a pot or cauldron was used to boil the fermented tuba to evaporate the alcohol called steamed tuba[8].

The general history of beer tells us that distillation appears long after fermented beverages. It takes a long period of economic and social practice with fermented beverages before distilled spirits become accepted by a people or community, even when they are brought by settlers. Whenever it has been said that distilled spirits first arrived among peoples ignorant of alcoholic beverages, this has been a mistake, as for example among the Amerindians of North America. This is also the case with the Australian Aborigines. The rapid adoption of distillation techniques implies a long presence of simple fermented beverages. The case of tuba distilled in the 18th century by the peoples of the Torres Strait implies a very early incorporation of fermented beverages into their customs, economic life and collective behaviour.

These data remain too parsimonious to draw up a history of aboriginal brewing in Australia, before and after its colonization. However, we can say that the indigenous peoples of terra australis made fermented beverages and that some even brewed beer. This is not a small discovery. Until now, almost every anthropologists asserted that hunter-gatherers could not know any other alcoholic beverages than those produced with sap and honey collected in the hollows of trees, or berries and fruits picked in the right season. That is beverages resulting from the spontaneous fermentation of natural sugars. Beer brewed with starch transformed into sugar seemed out of reach and reserved for the first farmers or horticulturists of the planet. We need to reconsider this scheme.

This is a more important issue than it seems. The difference between simple spontaneous fermented beverages such as wine or mead and beverages made with starch such as beer is technical. Brewing beer requires technology to process the starch. Yet this is not the only difference. There is a socio-economic difference between these two types of fermented beverages. Brewing beer with regularity requires a permanent source of starch, either as plants available all year round (roots, tubers, palm pith) or in a stored way (grains from cereal or pseudo-cereals). It also requires a mental universe, a collective consciousness, and social behaviours that welcome intoxication and give it a shared meaning for the wider community. When starch, which requires effort, time and technicality, enters the food arsenal of a community, brewing beer or making bread engages the whole of collective survival. To put it another way, consuming fermented fruit is compatible with individual drunkenness. Allocating a part of the collective starch resources to brew beer is a collective action. Drunkenness and the resulting behaviours should be subject to a social control.

So beer on the one hand, wine or mead on the other, are not the same matter regarding the type of social organisation, the food techniques and the collective behaviour associated with drunkenness. This is why the aboriginal brewery on the terra australis stands as an exemplary case.

Did all the indigenous peoples of Australia brew beer? We don't know. The earliest descriptions of Aboriginal peoples are frustrated and completely dominated by European colonial ideology. Terra Australis was considered by the British crown to be terra nullius, a land untouched by sovereignty inhabited by primitive peoples who had no rights to the land they had lived on for millennia.

These myths die hard. The existence of traditional Aboriginal fermented beverages was reported by Sydney and Perth newspapers in 1923 and 1929 respectively. The former describes the making of a wine from Banksia flowers. The second describes the same beverage made by the Bibbulmun people with this tree (mung-gaitch) in 1829, before the establishment of the city of Perth[9].

For the latter, the year 1770 means the beginning of the invasion. For the history of brewing in terra australis, it is the erasure of any knowledge of it, the beginning of the myth of the newly established Western brewery in the Austral lands and the symmetrical myth of the 'natives' who were unaware of the existence of fermented beverages, symbols of the culture of civilised peoples.

It is uncertain that this article will shift position lines, even a little bit.

Sources & bibliography :

Brady Maggie (2017), Teaching ‘Proper’ Drinking. Clubs And Pubs In Indigenous Australia. Centre for Aboriginal Economic Policy Research College of Arts and Social Sciences The Australian National University, Canberra Research Monograph No. 39. press-files.anu.edu.au/downloads/press/n3925/pdf/book.pdf

Brady Maggie (2016), Alcohol Fermentation in Australian Aboriginals. Encyclopaedia of the History of Science, Technology, and Medicine in Non-Western Cultures, pages 184-191. researchers.anu.edu.au/publications/104642

Brady Maggie, McGrath Vic (2010), Making Tuba in the Torres Strait islands: the cultural diffusion and geographic mobility of an alcoholic drink. Journal of Pacific History 45, 315–330. doi.org/10.1080/00223344.2010.530811

Brady Maggie (2008), First Taste. How Indigenous Australians Learned About Grog (Alcohol Education and Rehabilitation Foundation Ltd, Canberra). nationalunitygovernment.org/pdf/2016/first-taste-how-indigenous-australians-learned-about-grog-maggie-brady.pdf

Gibbs, H.D.; Holmes, W.C. - Gibbs, H.D.; Holmes, W.C. (1911). The Alcohol Industry of the Philippine Islands Part I: ". The Philippine Journal of Science: Section A. 6: 147-205.

Gibbs, H.D.; Holmes, W.C. - Gibbs, H.D.; Holmes, W.C. (1912). Part II: Distilled Liquors; their Consumption and Manufacture, Part III: Fermented beverages which are not distilled" The Philippine Journal of Science: Section A. 7: 19-45; 97-120.

Grey (1845), Journals of Expeditions of Discovery Into Central Australia, and Overland from Adelaide to King George's Sound, in the Years 1840-1 Vol. II. books.google.com.au/books?id=RiAQAAAAYAAJ&pg=PA250#v=onepage&q&f=false

MacPherson John (1921), The use of narcotics and intoxicants by the native tribes of Australia, New Guinea, and the Pacific, Sydney University Medical Journal, May (1921), 108–22.

Stilltoe Paul (1983), Roots of the Earth: Crops in the Highlands of Papua New Guinea. Manchester, UK: Manchester university Press.

Thomas N. W. (1906), Natives of Australia. The Natives Races of the British Empire, London 1906. archive.org/details/nativesofaustral00thomuoft/mode/1up?view=theater

Varela Cristian, Sundstrom Joanna, Cuijvers Kathleen, Jiranek Vladimir, Borneman Anthony (2020), Discovering the indigenous microbial communities associated with the natural fermentation of sap from the cider gum Eucalyptus gunnii. Scientific Reports 10:1. www.nature.com/articles/s41598-020-71663-x

Website :

Revealing the science of First Nations fermentation processes nationalunitygovernment.org/content/revealing-science-first-nations-fermentation-processes

[1] Quoted after https://www.brewers.org.au/about/history-of-beer/

[2] La Pérouse keeps a calendar to ensure that no sailing between two ports of call exceeds 68 days.

[3] In the 18th and 19th centuries, settlers used aborigines to collect honey in the bush, which they themselves did not know how or did not want to do. Wollombi tribe collects wild honey in the North West, 1861. Trading with the Wollombi, Edward Hargraves of Norahville supplied more than a tonne of honey a year to the Dixson Tobacco Factory (Newcastle & Hunter Society, vol 1, no. 2, dec 1972, courtesy of Carl Hoipo).

[4] The Eucalyptus gunnii trees originate from the Central Highlands of Tasmania at about 1,000 metres above sea level. Perhaps the easiest material to use from these trees is the sap. theconversation.com/alcohol-brewed-from-trees-and-other-fermented-drinks-in-australias-indigenous-history-96127

[5] The search for new wild yeast strains was part of the motivation and funding for this research on behalf of the Australian wine industry.

[6] Anglicised form of an Aboriginal term from New South Wales. https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Coolamon_(vessel)

[8] The distilled coconut alcohol has many local names: lambanog in the Philippines, uraca in some Pacific islands, arrack or aguardiente, both borrowed from the Indian Ocean, the other from the Spanish settlers, and many other names.

[9] A paper about aboriginal flower fermentation published by The World's News (Sydney) 8 Sep 1923 p. 8

A paper about aboriginal flower fermentation published by Western Mail (Perth) Thu 4 Jul 1929 p. 70

people near Merbein engaged in recreational activities by William Blandowski & Gustav Mützel, 1857.jpg)

, a wine from coco nuts milky white variety.png)