Your search results [2 articles]

1 - The carob tree beer of the Amerindians of the pampas in the 16th century.

Entire peoples have disappeared, bearers of human cultures of unprecedented richness.

With them, their fermented beverages and the kinds of beer they had invented.

Among these is carob beer.

It is the contribution of the Native Americans of Southern America to the world history of brewing.

In 1520, the expedition of Magellan skirts the coasts of South America. The sailors saw on the shores the Amerindians Tehuelches. It is their first contact with one of the peoples who inhabit what will become much later Argentina and its province of Patagonia.

Over the centuries and the episodic contacts that followed, the Europeans and their maps of the South American continent grouped together under the name of Patagons these manifold peoples and their diverse human cultures. They call Patagonia the land that stretches from the Rio de la Plata to Tierra del Fuego, the southernmost tip of the continent[1].

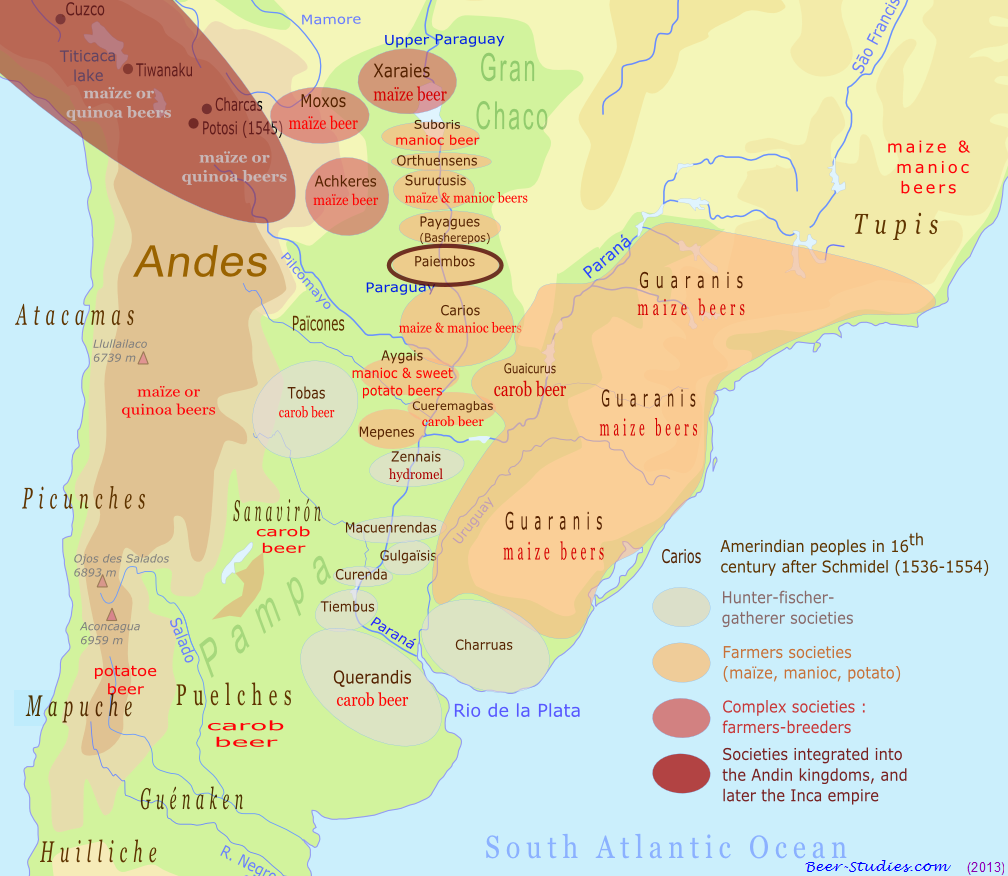

These Patagons actually form several confederations (see map). Their lifestyles are adapted to very different ecosystems: pampas in the centre, high tablelands of the Andean Cordillera in the west, subpolar forests, mountains and glaciers in the south, and the fish-bearing coastlines of the Atlantic and Pacific barriers. Hunting and fishing are the main sources of their subsistence.

A Spanish expedition led by Don Pedro de Mendoza went up the Rio Paraná and its tributaries in 1536. In less than 20 years, successive Spanish captains explored a region stretching from the mouth of the Paraná to the upper reaches of Paraguay, almost 2000 km as the crow flies. The Paraguayan river has its source in the Gran Chaco. It is the hot and dry country of the carob tree, the territory of the Amerindian peoples who know how to brew the carob beer.

The Spaniards meet there the Cueramaybas. The carob beer is their fermented beverage. The carob is the fruit of the Prosopis, the emblematic tree of the region.

« After eight days of going upstream, we arrived on the territory of a large tribe, named Cuérémagbas, which feeds on meat and fish. They make wine [beer] with the juice of a plant which is called in German johanns brodt or bockhornlein [holy bread John or goat's horn[2]]. They welcomed us with the greatest kindness and provided us with everything we needed. » (Schmidel, Chap. XIX, Du fleuve Parabol [Paraguay], des indiens Cuéremaybas et Aygais, pp 81-82)

« After eight days of going upstream, we arrived on the territory of a large tribe, named Cuérémagbas, which feeds on meat and fish. They make wine [beer] with the juice of a plant which is called in German johanns brodt or bockhornlein [holy bread John or goat's horn[2]]. They welcomed us with the greatest kindness and provided us with everything we needed. » (Schmidel, Chap. XIX, Du fleuve Parabol [Paraguay], des indiens Cuéremaybas et Aygais, pp 81-82)

We know from Schmidel that the Spaniards crossed the territory of the Cuéremaybas around May 1539[3]. The carob pods ripen during the southern winter (Nov-December). This proves that the Amerindians of the Plata basin knew how to preserve carob flour and make beer from it beyond the carob beans harvest season.

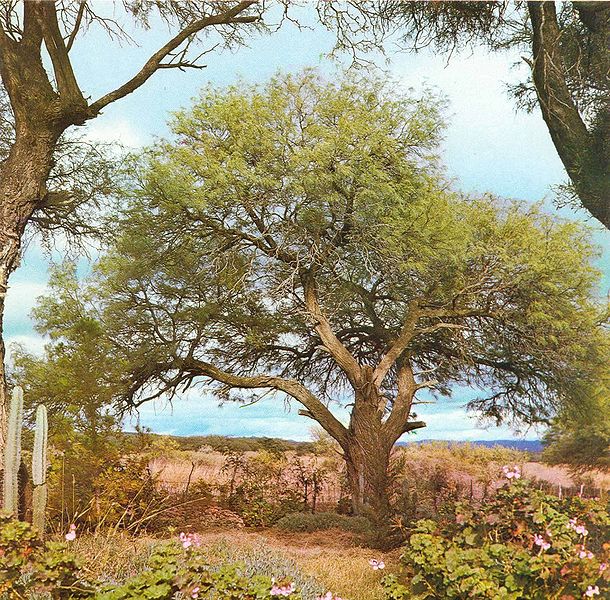

The Johanns brodt that Schmidel refers to is the carob tree. The tree produces pods called carobs every year. When they are ripe, the pods contain floury beans. Dried and powdered, these carob beans produce a flour that keeps well. This flour is an excellent raw material for brewing beer.

The Indians Guaycurus (Guaycurues) lived on the outskirts of Asunción, a town located a little north of the confluence of the rivers Paraguay and Paraná. They too knew how to brew the carob beer:

« This nation [the Guaycurus], and others who live on fish, also eat a species of local garoube. They go to the mountains to find these fruits, where the trees that bear them grow, such as the wild boars [tapirs], which all go to the heights at the same time. This takes place when the garoubes are ripe, from November to the beginning of December; they make flour and wine [beer] which is so strong that they get drunk. " (Comments of Alvar Nuñez, 123)

A Spanish expedition continues its journey northwards up the Paraguay River. The Paiembos live in the Gran Chaco, along the river. This typical society of the Gran Chaco is conditioned by its semi-arid environment which contrasts with the humid forests of Paraná where manioc and sweet potato grow. The carob tree (Prosopis) tolerates hot, dry climates and lack of water well. It also has the peculiarity of producing its pods in the hot season, when the other species dry out under the sun. The Paiembos were quite naturally brewers of carob beer :

« We stayed six months in the town of Assumption to rest. Our commander asked the Carios, our allies, for information about the Paiembos nation; they replied that these Indians lived one hundred miles [400 km] from the Assumption, up the Parabol river. Ayolas also inquired about their morals and customs, and whether they had much to live for. He learned that they lived only on meat, fish, and a plant called algarobo [algarroba = carob], from which they made flour that they ate with the fish. They also prepare with this plant a fermented beverage, which has a sweet taste and is similar to that of mead. » (Schmidel, Chap. XXIII, 100)

What about the Amerindian peoples living south of the Rio de la Plata?

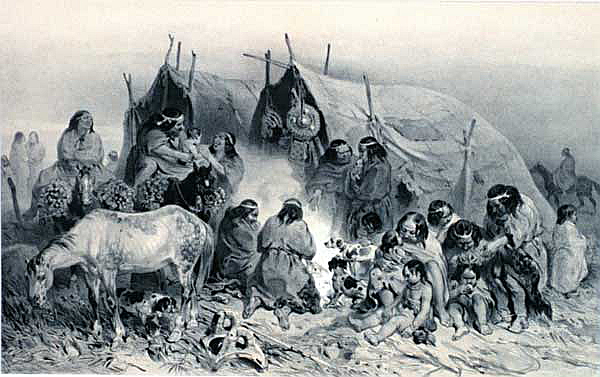

They inhabit the dry pampas which at that time was still covered with forests. The carob tree is also the endemic tree of the pampas. It must be assumed that the Amerindians of the pampas also know how to brew beer with the carob beans. The testimonies are rare but unequivocal. A. Guinnard is a key informant. He lived among the peoples of the pampas for 3 years, captured by them and more or less taken prisoner when he wanted to cross the continent from the rio de la Plata to join the Spanish colony of Chile in the middle of the 19th century. His testimony is late compared to the Spanish conquest of Paraguay. However, it shows that the brewing of carob beer in the pampas resisted contacts with the Spanish and the many waves of European settlers who came to make their fortune in that region.

The brewing of the carob beer

According to A. Guinnard, who lived for three years (1856-1859) among the Mamuelches, Tehuelches and Puelches, Amerindian peoples of the Pampa and Patagonia. His description of the brewing method is exceptionally precise. It is an excellent example of brewing by the acid method (no fermentation, germination or unsalivation). It takes place in 2 phases: an acidulous preparation of locust beans in a leather container that houses the microorganisms, then the addition of boiled carob beans, thus of fermentable starch:

« The Indians gather large quantities of algarrobos that they crush between two stones and put them in leather pouches filled with water, in order to obtain the soe-poulcou, a beverage that they leave to ferment for several days and on which a foam is formed that they carefully remove; they add another portion of boiled algarrobo and mix it all together while stirring it strongly. This preparation is quite pleasant and intoxicates them completely; but they cannot drink a large quantity of it without fearing violent colic and nervous contractions that will completely knock them down. They also eat raw algarrobo, but with a lot of caution, because this fruit, although very sweet, contains an acid which makes their lips, gums and tongue swell, and at the same time causes them a burning dryness which often prevents the least reasonable from eating for one or two days. » Guinnard Auguste 1856-1859, Trois ans chez les Patagons, éd. Chandeigne, pp 169-170.

Prosopis, the pseudo-carob tree of South America.

Prosopis (mimosaceaes fam.) is a close relative of the carob tree (fabaceaes fam.). The Spanish settlers named algarrobo all varieties of the tree , deceived by its resemblance to the Eastern European and Mediterranean carob tree, Ceratonia siliqua.

There are several endemic varieties of Prosopis in Argentina and Chile.

The Prosopis has vernacular names in language guaraní: "ibopé " or "igopé ". The beans of Prosopis provided the Guaraní tribes of Paraguay with a nourishing flour and enough to brew beer when maize was lacking.

All these species of Prosopis originate from South America. The centre of polymorphism of the species is Argentinean[b], particularly the regions of the Gran Chaco and the Sierras that border the Andes Cordillera. The climate is hot and dry. The Prosopis supports the lack of water and the salty or sandy soils. The carobs ripen in November-December during the subequatorial summer. Prosopis is a tree 5 to 15 m high and more or less one meter in diameter. Its trunk is short, the bark is thin, dark grey, and its wood is veined with tanning properties.

The fruit is a 20 cm long pod, with dark seeds 7 mm long, containing the patay, a sweet paste very rich in calories. More than half of the weight of the fruit is made up of sugars, the remaining of starch. The beans are converted into flour for human consumption, or consumed by animals with the fodder.

This fermented beverage produces an alcoholic drink, which the Métis populations of South America, who settled after the Spanish conquest, called aloja. In Brazil, Uruguay and Argentina, this Creole name designates traditional beers made from carob, rice or corn. Many people do not know that these carob and corn beers have an Amerindian origin.

- [a] http://www.hort.purdue.edu/newcrop/duke_energy/Prosopis_alba.html

- [b] Burkhart Arturo, 1976, A Monograph of the Genus Prosopis, Journal of the Arnold Arboretum v. 57, 221. A MONOGRAPH OF THE GENUS PROSOPIS.

Acarete du Biscay (therefore originally from the Basque Country) travelled by land in 1658 across the Argentinean pampas from the Rio de la Plata to the silver mines of Potosí, in present-day Bolivia. An adventurer in search of wealth having heard about the smuggling of silver ore between southern Peru and Argentina and the possibility of deceiving the surveillance of the Spaniards who reserved the exclusivity of this traffic. His account is an important source of the history of Argentina and Peru during the first decades of Spanish colonisation[4]. To the west of Córdoba (province of Tucuman between the Paraná River and the southern cordillera), Acarete confirms the presence of the carob tree forests from which a beer is made :

« From Cordoua [Cordoba] I took the road to St. Jago de l'Estro [Santiago del Estero], which is 90 leagues away [approx. 400 km]. During my journey I met from time to time, that is to say every seven or eight leagues, isolated houses of Spanish and Portuguese people who live very lonely; they are all situated along small rivers, some of them in the corner of forests which are very frequent in this region, and almost all of them are woods of algarobe, the fruit used to make a drink which is sweet, acidulous and healthy like wine; others are in open fields, which are not populated by herds like those of Buenos Ayres, but where there are however many, surely enough for the subsistence needs of the inhabitants, who also trade in mules, cotton, and the dyeing cochineal that the country produces. » Acarete du Biscay, Relation des voyages dans la rivière de la Plate, 31.

The Spanish Jesuit missionary José Sanchez Labrador arrived in the Rio de la Plata in 1734, almost two centuries after the first Europeans settled in the region. The country was already profoundly transformed. The Amerindian peoples have suffered the cultural shock of the conquest, the progressive monopolisation of their territories, and epidemics. Their cultures and their resistance forces are very weakened, except in the south of the Rio de la Plata, regions neglected by the Spanish and the European colonists.

The missionary travels through a large part of the territory of the Indians Guaranis, Chiquitos, Pampas, M'bayas, i.e. the basin of the Rio de la Plata and the adjacent southern territories. He lives in their midst, far from the colonial front and its influences. His studies on the customs and life of the Amerindians of the pampas are among the most complete and important.

The brewing of carob beer is noted, as well as the drinking manners. Unfortunately, the missionary says nothing about the making of carob beer, nor about its authentic Amerindian names:

« It is difficult to understand how much Indians love brandy, both women and men. To get some, they sell everything they have. At the mere sight of this liquor, they lose all judgment, even before they drink it. (...) They also prepare chicha [5] or strong carob beer and they can go on drinking almost indefinitely as long as they have spare. They have a superstitious ceremony. In fact, they do not drink the first chicha they prepare because they spread it with songs, shouts and tears on the bones of their ancestors which are kept in caves in the mountains. When this ceremony is over, they celebrate their drinking in the following way: the adults sit around the chicha in the tent (boys and girls are excluded) and take turns singing and drinking until the beverage runs out. Then they dress up in the herds they own and go out on their own singing. In these moments they rub each other and between songs they exchange a few insults and then they come to blows. » (José Sanchez Labrador, cité dans Guinnard 1856, 331)

The beer of Prosopis was thus widespread throughout the southern Amerindian sphere, from the Rio de la Plata to the south of present-day Argentina.

In the 16th century, carob beer was brewed by all the peoples of the pampas, from the Gran Chaco in the north to the south of the Rio de la Plata, a region still covered with forests.

It is likely that the technique of carob beer dates back to the time when the Amerindian peoples inhabited the region en masse. The cultivation of maize, and the horticulture of manioc and potatoes, were adopted later, the first coming from the Andean highlands, the second from the Amazon basin, with the peoples having migrated to the south of the continent.

According to Schmidel's testimony, certain peoples who had become maize and manioc farmers with whom they brew their beers did not however forget or abandon this ancestral technique of carob beer in the 16th century. They make it a seasonal fermented beverage, when the carobs beans are ripe once a year in November-December.

In the southern part of the continent, what is now Patagonia, the carob tree no longer grows. The presence of a tuber beer (the capac of the Tehuelches Indians met by Pigafetta and Magellan's expedition) is not attested among the ancient Amerindian peoples, at least to our knowledge.

[1] This Patagonia of early narratives encompasses the Rio de la Plata, the neighbouring northern territories (now Uruguay) and the region between Buenos Aires and the Andean Cordillera. Current Patagonia refers only to the southern cone of America, i.e. the southern provinces of Chile and Argentina.

[2] Schmidel knows the Carob Tree (Ceratonia siliqua), or Saint-Jean Tree(Baptist), Johannsbrot, in its European form originating from the countries around the Mediterranean. Every year, it produces pods (carobs) whose beans, once dried and then crushed, provide a fermentable flour, thus an ideal raw material for brewing beer.

[3] The Spaniards conquered Lampère, a city of the Carios, on August 15, 1539 ("We seized Lampère in 1539, the day of the Assumption of the Virgin. That is why we gave him this last name (Asunción), which it still preserves.", Schmidel, chap. XXII, 95). The territory of the Carios was 50 miles (about 225 km) upstream from that of the Aygais, itself 35 miles (about 150 km) from that of the Cuéremaybas. Juan de Ayalas' troop took about 2 months to go up the river from the Cuéremaybas to the Carios, and to stop in their villages, at a rate of 3,5 miles (14 km)/day.

[4] In 1672, Acarete published an account of his journey, then in 1696 a second version in Paris under the title Relation des voyages dans la rivière de la Plate. An English translation appeared in 1698.

[5] The term chicha is a Spanish generic term for all kinds of Native American fermented beverages.