Your search results [18 articles]

The psychotropic plants and the Amerindian beers in North America.

Have psychotropic plants replaced fermented beverages in North America to support ceremonies, collective celebrations, rituals and daily events? If so, for what reasons and according to what socio-cultural mechanisms?

The list of psychotropic plants used in North America for more than a thousand years is long: from tobacco to sumac, from highly caffeinated and vomiting plants such as Ilex vomitoria or cocoa (the bean but also the fermented pulp), to peyote and datura roots.

Almost all North American Amerindian peoples use psychotropic plants, a tradition older than the 16th century[1]. Unfortunately, European texts dating back the first contacts rarely explain the use of psychotropic drugs and the underlying beliefs. Consequently, this understanding, devoid of any historical dimension, extrapolates from modern observations. Speculations on shamanism, natural medicine and Indian spirituality present the religious behaviours of the Amerindians wrapped in primitivism. The description of these so-called 'natural' religions oscillates between a negative pole (beliefs and superstitions of the Savages) and a positive pole (authentic connection with natural forces). These speculations reflect the shifts in opinion within the White American society regarding the disappearance of Native American cultures. They tell us nothing about the Native American social structures and their history.

The European classifications dividing fermented beverages and psychotropic plants do not match the Ameridians' uses. Wherever they brew beer, they add plants that reinforce and modify the often moderate effects of low-alcohol beer. A non-exhaustive list in addition to the plants already mentioned: "crazy medicine" (root of Lotus Wrightii), "make noise" (Cassia Couesii root), "medicine sticks" and aromatic root or roasted seeds of Canotia holocantha. The White Mountain Apache sometimes add the roots of Datura meteloides and other plants to their tulapa beer. The list of stimulating or psychotropic plants added by the Amerindians to their beers is very long and the expected effects can vary significantly (Yanovsky 1936). The antagonistic categories beer OR psychotropic drugs are in fact irrelevant. North Amerindians discovered caffeine long before Europeans “discovered” North America.

Every morning, every day, 85% of Americans alter their state of consciousness with a potent psychoactive drug: caffeine. Nobody would dare compare caffeine with alcohol. The split into two distinct classes of these beverages is so familiar. Was it true for the Amerindians peoples?

The tobacco in ceremonies, political dealings, medecine and everyday life.

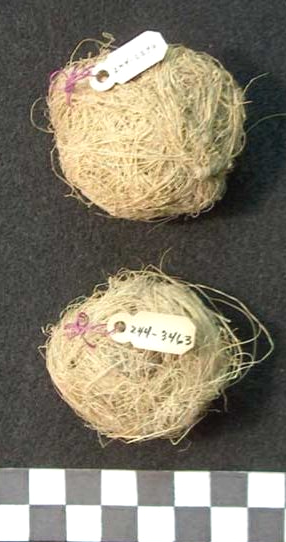

The oldest documented uses of tobacco date back 1200 years. Pouches made with Yucca fibres and containing wild tobacco leaves (Nicotiana attenuata) were found in the Antelope Cave in north western Arizona (Adams & al. 2015).

Tobacco seems to be the most widespread use. The earliest evidence for North America dates back to Jacques Cartier's encounter with the Iroquoian Indians on the banks of the St Lawrence in 1535. Tobacco is of ordinary and daily use, with no immediate connection to a ritual, or communication with the spirits:

“They also have a weed of which they make great heaps in the summer for the winter. This they value highly and use it for men only in the following way. They dry it in the sun, and wear it on their necks in a small animal skin in place of a bag, with a horn of stone or wood: then at all hours make powder of the said herb, & put it in one of the ends of the said horn, then put a coal of fire on it, and suck from the other end, so much that they swell their body with smoke, so that it comes out of their mouth, & through their nostrils, as through a chimney pipe: & say that this keeps them healthy and warm, & they are never without the said things. We have tried the said smoke, after which we have put into our mouth, as if we had put pepper powder in it, so hot is it.” (Cartier 1535, 31)

The same tobacco was used in political ceremonies or negotiations, when people smoked the pipe with their former enemies or new allies. The exchanges between the Iroquoians and the French foreshadowed what would be repeated ad infinitum in subsequent contacts. The Indians brought the sailors "many eels & other fish, with two or three loads of big millet [maize], which is the bread they live on in the said land, and several big melons”. In exchange, Cartier had “bread and wine brought to make the said lord [Donnacona] and his band drink and eat”. Cartier went to the Stadacone village of Chief Donnacona. The French learned to smoke tobacco with a pipe, the Iroquoians to drink brandy. A mutual discovery. Tobacco thus has many uses and displays different symbolisms depending on the context.

Among the Hurons, collective deliberations took place while smoking tobacco. They are described by Gabriel Sagard, a missionary of the Recollet order, who lived among them in 1623-24: “When they are all assembled, & the Hut closed, they make a long pause before speaking, so as not to be hasty, yet always holding their Calumet in their mouths, then the Captain begins to harangue in terms & speech loud & intelligible for a fairly long time, on the matter they have to deal with in this council: having finished his speech, those who have something to say, one after the other without interrupting each other & in a few words, give their reasons & opinions, which are then collated with straws or small rushes, & on this is concluded what is deemed expedient.” (Sagard 1632, 199)

Kinnickinnick (an Ojibwe word) literally means "what is mixed," and refers to plant materials that Indian people mixed with tobacco for smoking. Use of kinnickinnick was widespread in North America, but the ingredients varied regionally. In the Woodlands, the favorite ingredients were the inner bark of certain willows, dogwoods, or sumac leaves. The final mixture usually only contained about one-third tobacco.

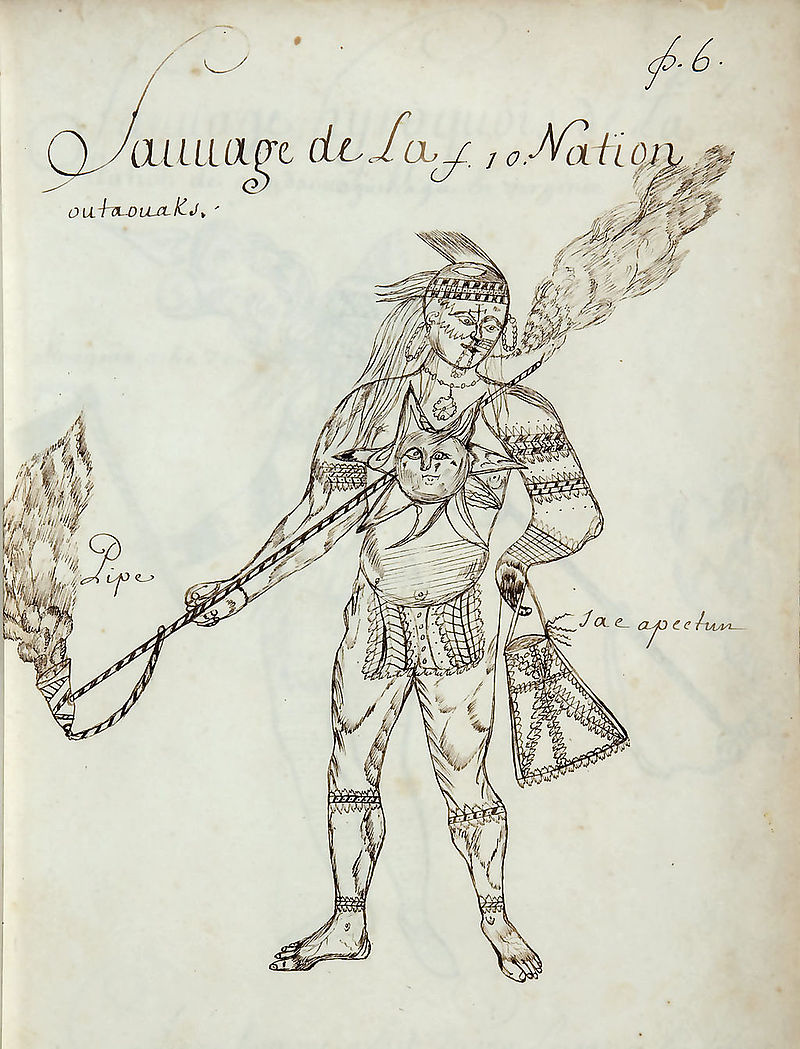

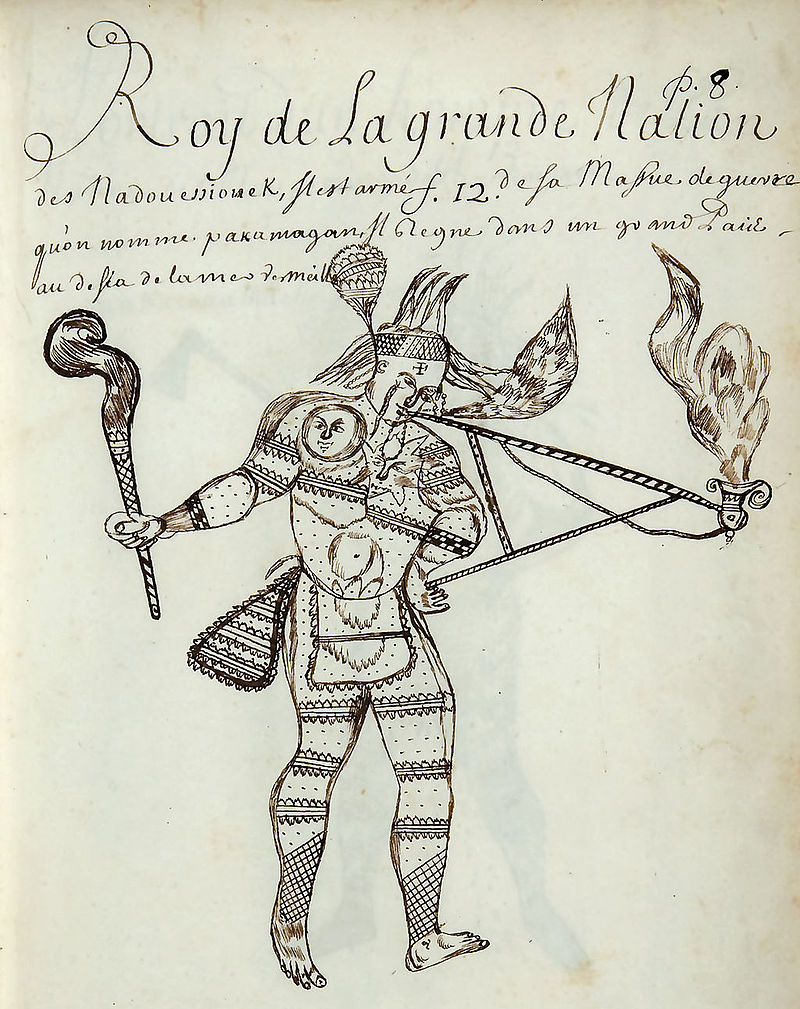

| Ink drawings by Louis Nicolas made around 1675 during his 11-year stay in Canada => Codex Canadensis | |||

|

|

|

|

| Sauvage hyroquois de La Nation de gandaouaguehaga en virginie - attouguen ache de guere - Ce Jeune homme a fait en ma Presance son Essay de guerre se faisant arracher des ongles, couper le bout du nés par ses camarades qui le menoint comme en triomphe au tour du bourg voulant par la qu'on sceut qu'il soufriroit genereusement tous les tourments que les Ennemis de guerre lui fairoit souffrir en cas qu'il fut prix. | Capitaine de La Nation des Illinois, il est armé de sa pipe, et de son dard. | Sauvage de Nation outaouaks - Pipe - sac a peetun [tobacco]. | Roy de La grande Nation des Nadouessiouek. Il est armé de sa Massue de guerre qu'on nomme pakamagan, Il regne dans un grand Pais au dela de la Vermeille. [Sioux, living in present day Minnesota before 1700, now in Eastern Dakota] |

At the other end of the subcontinent, on the shores of the Caribbean Sea, no fermented beverage but tobacco to accompany a feast. In 1684, Henri Joutel joined Cavelier de La Salle on his third expedition to the mouth of the Mississippi: “This procession thus led us to the Chief's hut, where, having been a short time, we were taken to a larger hut a quarter of a league away; this was the hut where the public rejoicings were held, and the great assemblies. We found it lined with mats to sit on; the elders sat down around us, and we were brought to eat sagamite, which is their soup, small beans, corn bread, and other breads which they make with cooked flour, and finally we were presented with a smoke.” (Joutel 1684, 215)

The same Joutel testifies that the ceremonies of the first fruits of maize are not accompanied by any fermented beverage: “When the wheat is ripe, they gather a certain quantity of it into a basket, or a bin, & this basket is placed on a seat or a kind of ceremonial stool, which is intended for this purpose, & is only used in their mysteries, which they have great veneration for. The bin, & the wheat placed on the venerable stool, an old man stretches out his hands on it, & speaks a long time; then the same old man distributes the wheat to the women, & no one is allowed to eat new wheat, until eight days after the ceremony. It may be seen that by this they mean to offer or bless the first-fruits of their harvest. When they hold assemblies, & the sagamite [corn porridge], which is the most essential part of their meal, is cooked in a large pot, they place this pot on the ceremonial stool, & an old man stretches out his hands over it, & mumbles certain words between his teeth for a long time, after which it is eaten.” (Joutel 1684, 225-226).

The beverages from caffeinated and vomiting plants.

They are used in collective ceremonies: large meetings of warriors before going to war, collective decisions, various festivities. A decoction of leaves and berries of Ilex vomitoria Ait. (yaupon, yapon, yupon) or Ilex cassine L. (dahoon) rich in methylxanthines is heated for several days and then drunk in large quantities. This powerful emetic produces hallucinogenic effects. It is known in the literature as cassiné or black beverage. Its use is widespread in the South and South-East, the native regions of the plant.

Jacques Le Moyne de Morgues, a painter-soldier, illustrated and commented on a ritual scene of casiné consumption among the Timucuas Indians. Here is how he describes the role of this vomiting and hallucinatory beverage in the run-up to war expeditions: “The king orders the women to prepare the casiné, a beverage made from the leaves of certain plants whose juice is squeezed out. The cupbearer then presents it to the king in a shell and passes it to the other attendants. They appreciate this beverage so much that no one is allowed to drink it in the assembly unless he has shown courage in war. This drink is no sooner swallowed than it makes you sweat. Therefore, those unable to keep it, reject it, and are not entrusted with anything difficult, nor with any military office. After drinking this beverage, one can remain for twenty-four hours without eating or drinking anything. Casiné nourishes and strengthens the body, but does not go to the head.” (Le Moyne de Morgues 1591). So neither drunkenness nor alcoholic fermentation!

This ingestion was a test of endurance. The Timucuas and other Amerindian peoples of the Southeast used the leaves and stems in an infusion called asi or black beverage, intended to purify the men and unify the warrior groups. The ceremony involved vomiting (hence the epithet vomitoria) caused by the large quantity of beverage ingested. The active substance is caffeine, which the wild varieties of Ilex contain in high proportions: “If there is something to be dealt with, the king calls the jaruars, that is to say their priests and elders, and asks for their advice; then he orders that casiné, which is a beverage made from the leaves of a certain tree, be made and drunk while hot. He drank the first one, and then had everyone give it to him one after the other in the same vase, which held a quart, Paris measure. They pay so much respect to this beverage that no one may drink in this assembly unless he has proved himself in war. Moreover, this beverage has such a virtue that as soon as they have drunk it they become all sweaty, which, having passed, stops the hunger and thirst for twenty-four hours afterwards.” (Laudonnière 1564, 10)

In 2012, the chemical analyses of organic residues within fragments of beaker vessels dating between A.D. 1050 and 1250 from the large site of Cahokia and surrounding smaller sites in Illinois revealed the presence of Black Drink. This major discovery has identified theobromine, caffeine, and ursolic acid, as biomarkers for species of Ilex (holly) used to prepare the ritually important Black Drink contained in the pottery. This confirms that Cahokia was a major Amerindian site along the Middle Mississippi river where rituals has occurred during a period that scholars consider a pivotal time for the development of the Mississippian Cultural Complex. As Ilex plants are not native of the Mississippi areas, its consumption at Cahokia involved a large trade network which make them coming from the eastern or southern part of the American sub-continent. Forthcoming analyses should fill the chronological gaps between 800 and 1600, the timespan of the Mississippian and associated Cultures. Patricia Crown concludes: “First, the documentation of Black Drink at ∼ A.D. 1050 is the earliest known precontact use. Second it demonstrates the presence of Yaupon or Dahoon holly far north of their natural distributions, indicating their deliberate transportation. Third, it suggests that beakers may have been manufactured specifically to play a role in Black Drink ceremonies. Fourth, it reinforces other evidence for the existence of a fertility/life-renewal cult at Cahokia that included Black Drink ceremonies. Most importantly, it bolsters earlier suggestions that Cahokia played an important role in the subsequent religious developments in the Southeast.” (Crown 2012, 13947-48)

Did fertility cults in Cahokia include maize products, including beer? In the absence of dedicated research, this question remains unanswered.

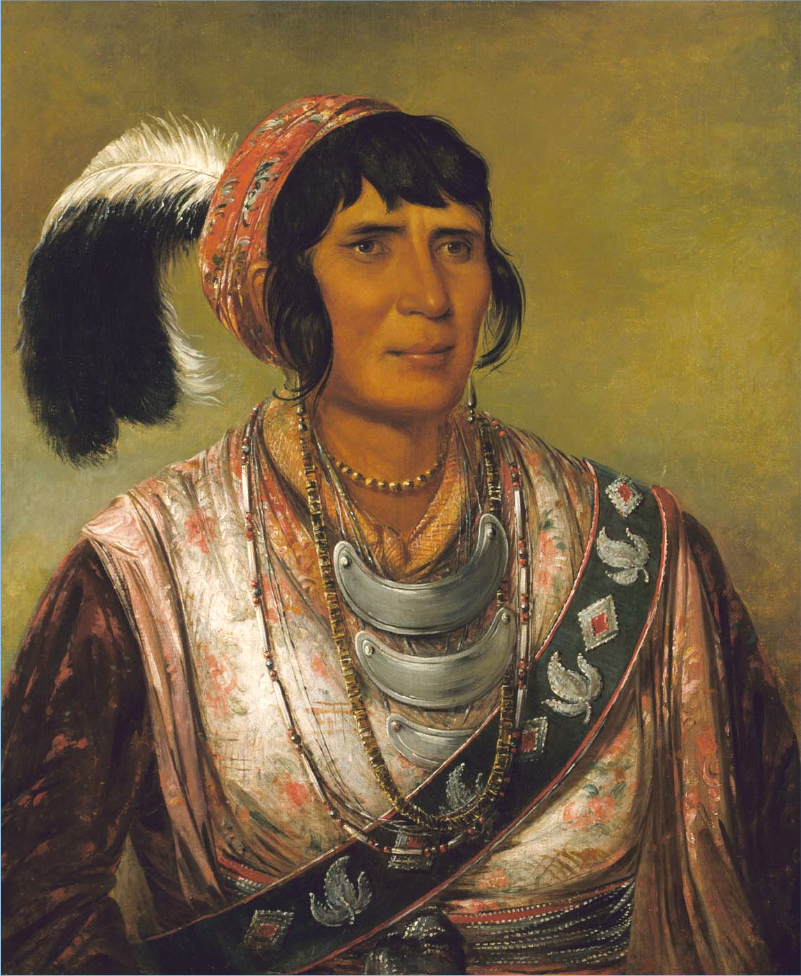

Osceola, or better asi-yahola meaning Black-Drink singer, a legendary Seminole chief from Florida. He led the Creek War (1813-1814) caused by the forced removal of the Creek people to the western regions decided by the US government.

Another Amerindian ritual beverage is made from cocoa. Its stimulating nature comes from the theobromine contained in the beans and the mucilage that envelops them, and from caffeine in a smaller proportion. Its use before the arrival of the Spaniards has been demonstrated by the analysis of organic residues preserved in beakers discovered in Pueblo Bonito (Chaco canyon, New Mexico). The beakers date from the years 1000-1125 (dating based on the decorative style), a time of strong integration or influence between Mesoamerican and Southwestern societies. The cocoa tree (Theobroma cacao) grows in the warm and humid regions of Mesoamerica. Its presence in the northern Chaco region implies an extensive network of exchange of prestige products. In Mesoamerica, the beverage is a mixture of ground beans with water, maize flour, chilli and other spices. It is a ritual beverage consumed by an elite. P. Crown argues that this was also the case in the Chaco region in the 11th century. The discovery of goblets and pitchers analysed in a cache in Pueblo Bonito suggests that their use was exclusive to a small fraction of society (Washburn 2011, Crown 2015).

This discovery tells us nothing about the status or use of beer in the same region around the 11th century. It does, however, confirm the existence of hierarchical, technically advanced Amerindian societies in the southwest, integrated into a large regional network of social and commercial exchanges. The cocoa that reached the Rio Grande was exchanged for local products, such as turquoises[2], which in turn implies a local trade throughout the Rockies ranges.

The psychoactive plants and the Amerindian beers.

The list of psychoactive plants used by the North Amerindians is quite long. However, historical accounts of their specific uses are quite scarce, especially when they concern the period of the first contacts.

Genista (Cytisus canariensis) is native to the North American area and has been well known by man Native American tribes for its psychoactive properties. Mescal Beans (Sophora secundiflora), can date historical usage back as far as nine thousand years ago. In North America, the Arapaho and various Iowan tribes have used the beans for centuries. The beans are commonly used as a safe hallucinogen for their “Red Bean Dance” rituals. The Peyote cactus (Lophophora williamsii) can induce realistic visual hallucinations. Peyote is more commonly employed in Mexico, where it grows in greater abundance.

The Saguaro cactus (Carnegiea gigantea) is growing in the Great Southwest and Mexico. It has been an important medicine to Native Americans. The fruit is usually what is valued, though various parts of the plant are psychoactive.

Sweet Flag (Acorus calamus) is mostly used by Native American tribes of Northern United States and Indians of Canada (especially the Cree), Sweet Flag helps with anti-fatigue, minor pain relief (such as against toothache and headache), and for treating asthma. Typically, the roots are chewed. Toloache (Datura stramonium) is also known as Toloatzin or Jimpson Weed (famille des solanacées). Toloache is most commonly employed by tribes in Southwest America (especially the Zuňi). It is a strong hallucinogen also implemented for many medicinal purposes.

As a result, we know little about the role of psychotropic drugs before the 16th century and even less about the changes caused by the arrival of Europeans. Most of the assumptions derive from the more known Aztecan customs which, like the maize beer, are supposed to have been adopted by Southwestern Indians around the 10th century. The literature has coined the ritual use of psychotropic drugs and shamanism a Native American cultural hallmark, with no reliable historical data going back beyond the 19th century.

Other scholars have pointed out that body techniques played as important a role as plants or psychotropic drinks:

“When Native American peoples wanted to transform consciousness – in the vision quest, for example – they did so with disciplines like starvation, concentration, isolation, and sleep deprivation.” (Moerman 2014, 4)

Assessing the relative weight of the latter versus fermented beverages is simply out of reach nowadays without accurate archaeological data.

[1] Hauffe (2019, 10) “Special use, botanicals such as tobacco, nightshade (https://fr.wikipedia.org/wiki/Solanaceae), and sumac, are markedly more visible throughout the American Bottoms during the Emergent Mississippian era than what is found in other Late Woodland sites to the south (Williams 2000). This is not to say such botanicals do not find their way into the archaeological record of southern sites during these earlier times; however, their inclusions are only found in feasting contexts or other areas considered to be of special use (Kassabaum 2014, Mitchem 2016, Vanderwalker et al 2017)”.

[2] The turquoise mined from the Cerillos deposits (New Mexico) has been found in northern Mexico and at Chalchihuites, but also at Chichen Itza in the Yucatan, with the same neutron activation signature (Kelley, 2000).

_man_leaning_back_slightly_with_strips_leather_attached_to_pole_ritual_Sun_Dance_that_lasted_at_least_four_days-Edward_S._Curtis_1908.jpg)