Your search results [5 articles]

The Achuar dwelling and the female brewers

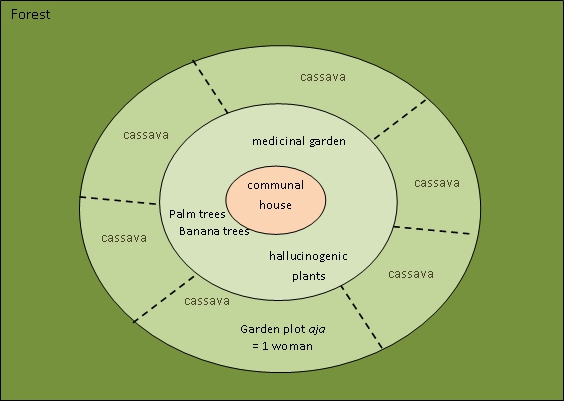

The Achuars are farmers (sweet cassava, yam, sweet potatoe, medicinal plants), hunters (monkey, toucan, ...), freshwater fishermen in the low-water season, and gatherers (palm, banana-tree, chonta, hallucinogenic plants). A village settles for 3-4 years near a river, clears land and practises a slash-burn culture to grow the plants it needs, around a hundred or more cultivars.

The symbolic space centred on the collective house

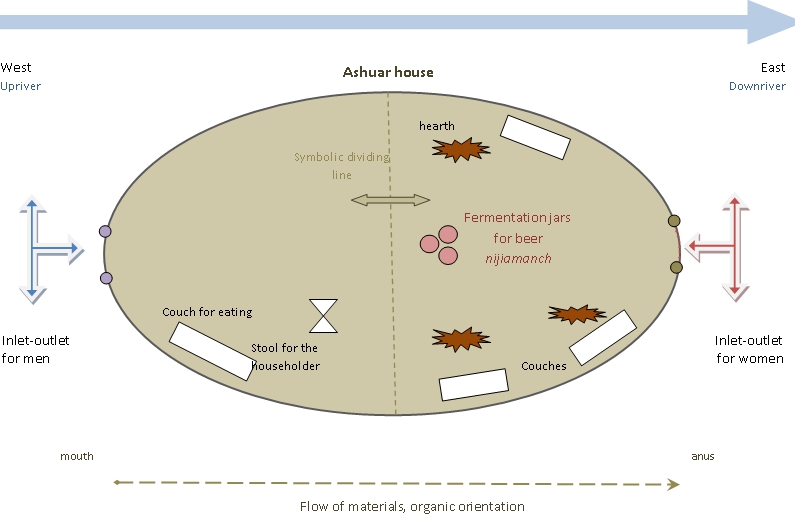

The space is organised in concentric circles around the house. It is a round or oval shelter covered with a palm leaf roof. Set up in small groups along the rivers, the houses are oriented east-west, parallel to the streams flowing eastwards on the slopes of the Cordillera. The first circle is occupied by medicinal plants, the palm tree and hallucinogenic plants (datura, ...). The plots cleared and burnt by men are cultivated by women for cassava. Beyond, this is the forest, the domain of the hunters.Les Achuars ne conçoivent pas la forêt comme un espace sauvage contrastant avec l'espace cultivé qui entoure la maison. They know that the forest is also the fruit of their regular movements over the centuries, of their clearings every 3 to 5 years. Each time they give up a clearing, the forest grows back but does not make the plants that the women have sown and which reproduce spontaneously disappear. The forest is also a vast garden that bears the traces of ancient cleared fields, an ecosystem that has been profoundly modified by humans under the appearance of an unfathomable jungle[1].

After the men have cleared the land, the cultivation of cassava and the brewing of beer are under the control of women. Men should not brew beer, handle the cassava or beer jars, or even touch the beer other than with their lips when they drink it. Beer is a living form. Its constant renewal and strength is a feminine knowledge and power. Just as a piece of cassava tuber replanted in the ground regenerates the whole plant, so the fermentation process recreates the beer with each brew. If a man touches the beer with his finger, this living creature is in danger of weakening.

The Achuars do not, like us, draw impervious borders between humans, animals, plants and certain natural manifestations. They all interact, they all meet each other in the human mental world. That of the Achuars is certainly more inhabited, richer and more complex than the functional and procedural universe of the modern western person. The use of hallucinogenic plants does not explain everything.

For them, beer is not a simple beverage that could be reduced to its thirst-quenching or intoxicating virtues. It conveys and communicates to humans the regenerative forces it draws from cassava, which itself holds the inexhaustible regenerative powers of the plant world and the earth. [2].

Organisation of the Achuar house

The saliva, which plays such an important technical role in the brewing process, also stands for a social difference.

The female saliva impregnates the chewed cassava dumplings. It ensures the success of the brewing process. Feminine orality is on the side of technique, know-how and power over cassava, the food material par excellence.

The men drink the beer without ceasing to throw small spurts of saliva out of the corner of their mouths. This spurt punctuates discussions, speeches and ritual welcoming speeches. It is the realm of speech, of the social, of negotiations, of war preparations, of family alliances, of collective celebration.

These two marks of the saliva distribute social roles according to a sexual polarity. The collective consumption of beer is a time when these two poles intersect: beer brewed with the saliva of women is drunk by men who punctuate their speeches with saliva thrown on the floor.

[1] Ph. Descola, La nature domestique. Symbolisme et praxis dans l'écologie des Achuar. 1986 (1ère éd. Singer-Polignac), 2019 (2ème éd. Maison des Sciences de l'homme), p. 250-258.

[2] « In the Achuar's mindset, the technical know-how is inseparable from the ability to create an intersubjective environment in which regulated relationships between people flourish: between the hunter, the animals and the spirits that control the game, and between the women, the plants in the garden and the mythical figure that gave birth to the cultivated species and continues to ensure their vitality to this day. Far from being reduced to prosaic places that provide food, the forest and the cultivated areas are theatres of subtle sociability where, day after day, one come for coaxing beings that can truly be distinguished from humans only by the diversity of appearances and the lack of language. The forms of this sociability differ, however, depending on whether one is dealing with plants or animals. The women are masters of the gardens to which they devote a large part of their time, and they address the cultivated plants as their children, who should be led with a firm hand to maturity. This mothering relationship is explicitly modelled on Nunkui's guardianship, the spirit of the gardens, over the plants she once created. Men, on the other hand, consider game as a brother-in-law, an unstable and difficult relationship that requires mutual respect and circumspection. In fact, in-laws form the basis of political alliances, but are also the most immediate adversaries in vendetta wars. The opposition between consanguinity and affinity, the two mutually exclusive categories that govern the social classification of the Achuar and guide their relationships with others, is thus found in the prescribed behaviour towards non-humans. Blood relatives for women, in-laws for men, the beings of nature become social partners in their own right.

But can we speak here of beings of nature other than for the sake of language convenience? Is there a place for nature in a cosmology that gives animals and plants most of the attributes of humanity? Can we even speak of wilderness in connection with this forest barely touched by the Achuar and yet described by them as a huge garden carefully cultivated by a spirit? What we call nature here is the subject of a social relationship; extending the world of the household, it is truly domestic even in its most inaccessible corners. » (Ph. Descola 1999, Diversité biologique et diversité culturelle, in UICN Célébrations du 50ème anniversaire, pp. 108-109 UICN 1999) (translation is mine)