Your search results [6 articles]

6 - Beer and the complexity of Amerindian societies in the 16th century.

A new expedition led in 1548 by Martin Domenico de Irala went up the Parabol River (Paraguay) in search of gold or silver.

« These Indians [the Maipais] are numerous; they have vassals who work and fish for them, and who are submissive to them, just as in our country the peasants are submissive to the gentlemen..

« These Indians [the Maipais] are numerous; they have vassals who work and fish for them, and who are submissive to them, just as in our country the peasants are submissive to the gentlemen..

The Maipais have an abundance of food, especially maize, manioc and all kinds of roots that are good to eat called mandeoch [manioc] ade, madepore, mandeoch, porpyre, padades [sweet potato] and mandues bachkeku [banana].

They also have deer, local sheep, ostriches, ducks, geese, chickens and all kinds of poultry.

In their forests there is a lot of honey, the natives prepare a fermented drink from it, which they use for all kinds of purposes. The further inland you go, the more fertile it is: you can see all year round fields planted with maize and roots I already mentioned [cassava and potatoes]. » (Schmidel, Chap. XLIV, Les chrétiens retournent à l'Assomption. – Ils font une expédition dans l'intérieur pour chercher de l'or. 197-198)

There are also federations of tributary peoples and larger political entities, organised in more hierarchical structures.

« We then entered the land of Indians named Zemies, they are vassals of the Maipais, as in our country the peasants are vassals of their lord. On the road we found a lot of maize and roots. This land is so fertile, that before the produce of one field is brought in, the produce of the neighbouring field is already ripe, and while this one is being harvested, a third one is sown, so that all the year round we have fresh food. » (Schmidel, Chap. XLV, Des tribus Mapais, Zemie, Tohanna, Peionas, Mayegoni, Morronos, Paronios et Symanos. 203)

The troop led by Irala reaches the foothills of the Andes and joins the Spanish colonies in Peru. On the outskirts of the Salinas del Jauru (16° lat. S.), Domenico de Irala sends two emissaries through the Andes to Lima. The Amerindian societies he describes are close neighbours of the Inca Empire.

« I have to notice that the land of the Machcakies is the most fertile land we have discovered in our whole trip. An Indian only has to go into the forest and make a notch in the first tree that comes along so that five or six measures of honey as clear as mead will come out of it. The bees that do this are very small and have no sting. The Natives make a drink with this honey that looks like mead, but is more pleasant to the taste. » (Schmidel, Chap. XLIX, De la fertilité de Machcakies. – Nous retournons où nous avions laissé nos vaisseaux. 226)

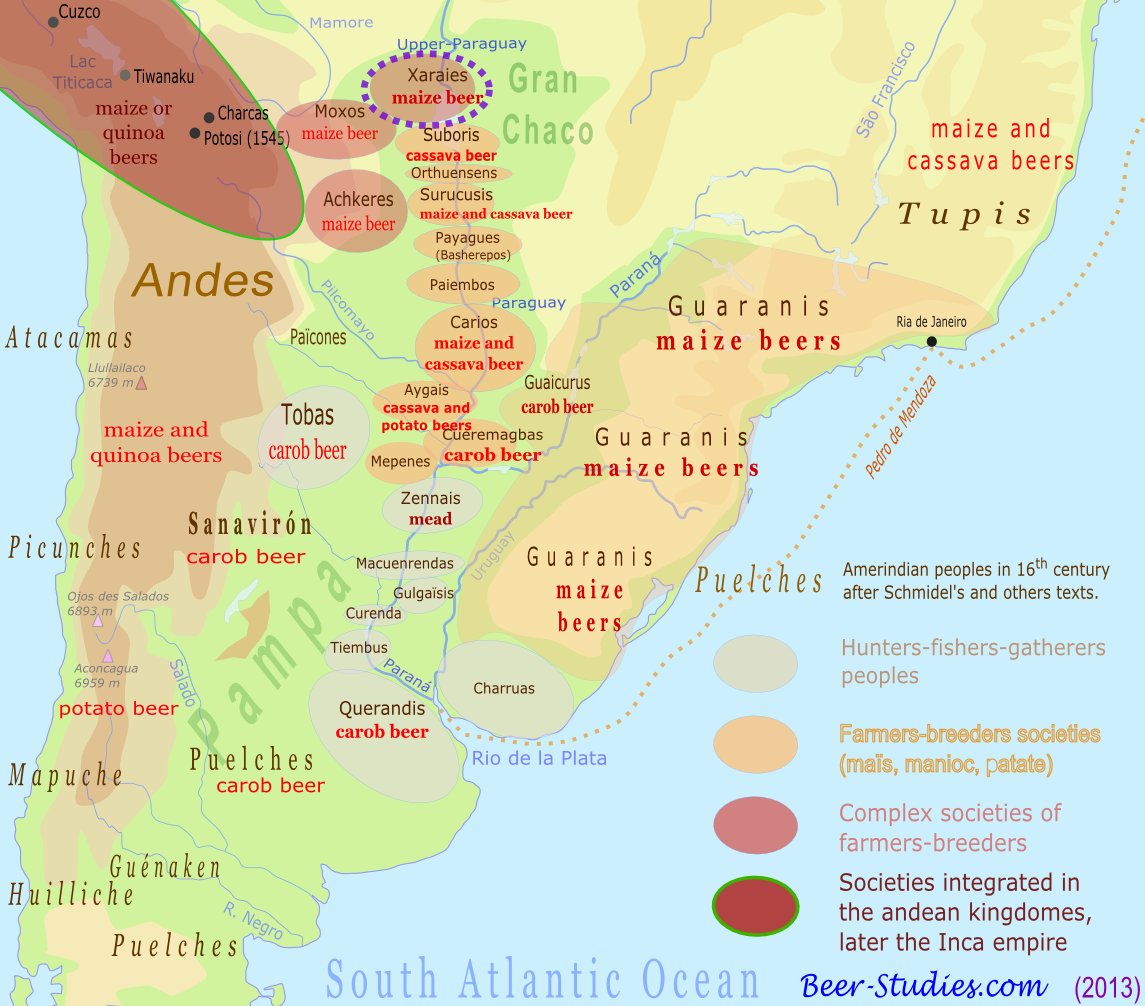

Amerindian Beer brewing peoples of South America before the Spanish colonisation.

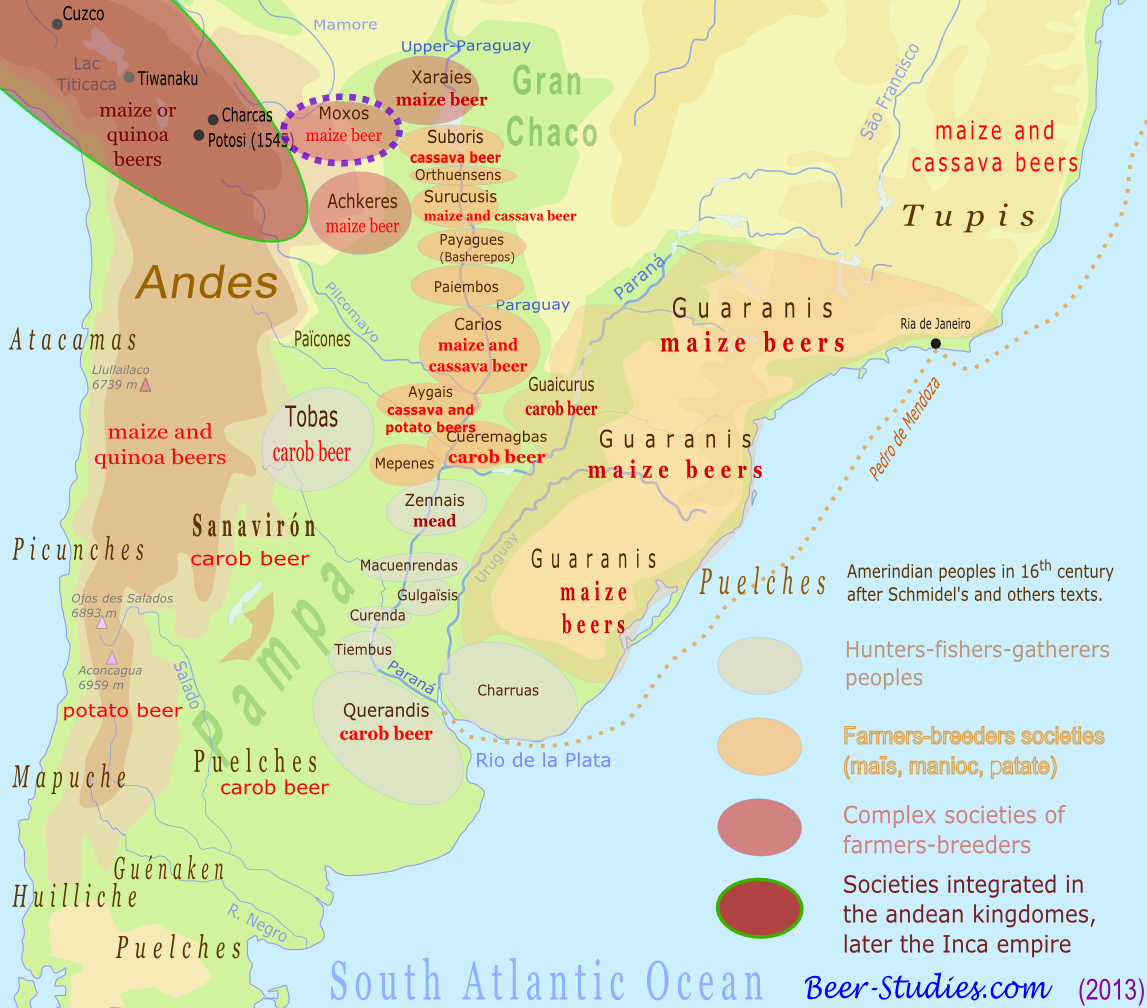

Amerindian Beer brewing peoples of South America before the Spanish colonisation.

In 1555, a vanguard of the Alvar-Núnez Cabeça de la Vaca expedition approached the territory of the Xarayes, (Xaraiés, "Masters of the River") on the upper reaches of the Paraguay river. They live in this vast semi-flooded plain, nowadays called Pantanal[1], on the border of Brazil and Paraguay. These farmers brew beer with their main cereal, maize. It is with this beer that they honour the Spaniards with their hospitality:

« Soon they reached other marshes [marshes of Pantanal], from where they did not believe they could get out, so difficult was the walk there. Besides burning their legs, they would sink down to their waist and it was almost impossible to withdraw from it. These swamps were more than a mile wide. Then they came to a firmer path. The same day, at one o'clock in the afternoon, not having eaten anything yet, they saw about twenty Indians coming in front of them by the same road. These people arrived, all happy, loaded with cornbread, baked geese, fish and corn wine [beer]. And they told the Spaniards how their leader, when he heard that they were going to their country by this road, had commanded to bring them food, and to speak to them on his behalf, and to guide them to him. » (Commentaires d'Alvar Núnez, 333)

The Xaraiés live near the foothills of the Andes. Their western neighbours are the Moxos, the Chicas, the Paicones, bearers of a culture influenced by the central Andes, the civilization of the Inca world. This influence is perceptible in the way the Xaraiés receive the Spaniards: central authority of a chief, council of elders, embryo of courtship, ceremonial reception of the foreigners with whom the Xaraiés chief wants to make alliance, white cotton dresses, etc.

« They put the Spaniards in their midst and led them into the village, at the entrance of which a large number of women and children were waiting for them. All the women covered this part which decency must hide; many of them were dressed in white cotton dresses which they used and which are called tipoes.

When the Spaniards reached the village, they went to the chief of the Xarayes. He was in the midst of three hundred very good-looking Indians, most of them elderly. This chief was sitting in a cotton hammock in the centre of a large square. All his subjects were standing and around him. As soon as the Spaniards arrived, the Indians lined up and made a passageway through which our people advanced. As soon as they were close to the chief, they were brought two small wooden stools which he signalled them to sit down. » (Commentaires d'Alvar Núnez, 334)

On the orders of Alvar Núnez, the captain Francisco de Ribera and 6 Spaniards accompanied by Amerindian guides went westwards in January 1544 from upper Paraguay, therefore towards the Central Cordillera, to reach a mountain called Tapuaguaçu. About 70 leagues (300 km) away, they meet some Indians Tarapecocis maize farmers who offer them maize beer as a welcome :

« The Indian brought the Spaniards into the house, from which the women and other naturals took everything out. In order not to pass in front of the Christians, they opened the straw of the walls and, by the gap they had made, they moved everything out. Our people saw some large boilers full of maize, large plates, axes, silver bracelets, which were taken away through the straw walls. This Indian appeared to be the head of the family, judging by the respect shown to him by the others. He welcomed the Spaniards into his home, beckoned them to sit down, and ordered two orejonès[2], that he had for slaves, to give them to drink maize wine [beer], which filled clay jars buried in the ground down to the mouth. They drew from these this beverage with two large gourds and presented it to the Spaniards. The two orejones said that three days' march away there were Christians, and Indians named Payçunos, and then they taught them about Tapuaguaçu, which is a great high mountain. » (Commentaires d'Alvar Núnez, 396)

The large communal house therefore shelters a full range of brewing equipment. Large pots for boiling, (clay) slabs for making maize loaves, and underground fermentation jars. This equipment requires a brewing organisation that goes beyond the occasional brew. Brewing beer is a permanent task and a social activity. Three days' walk westwards and further on, the Andes rise up. The Christians are probably Spaniards from the newly founded colony of Peru. The region is close to the Inca Empire and its cultural influence. This explains why maize beer is among the Tarapecocis Indians integrated in the welcome customs.

In December 1543, Captain Hernando Ribera, charged by Alvar Nuñez to explore the Upper Paraguay, left with 52 men and the Carios Indians. The troop enters the territory of the Xarayes Indians :

« After sailing for seventeen days, he crossed the country of the Perovacas Indians and arrived in another region, whose inhabitants are called Xarayes. These people gather a lot of food, they feed geese, chickens and other birds, they fish, they hunt, they are civilised and obey a chief. When the Spaniards arrived among the Xarayes, they entered a town of about a thousand houses, whose chief is called Camire. This cacique received him very well, and Hernando Ribera obtained some information from him about the peoples living inland. » (Relation d'Hernando Ribera, in Commentaires d'Alvar Núnez, 488-489)

This is indeed the description of a densely populated country, devoted to agriculture and animal husbandry, organised into villages which are themselves integrated into a larger, hierarchical social structure. The caciques are no longer mere village chiefs.

The cultural and political influence of Peru, which is no longer very far away according to Ribera's location, can be seen in the customs he has described:

« He walked for three days and reached the villages of an Indian nation called the Urtues; they are good people who cultivate the land like the Xarayes. From this place he travelled through a completely inhabited area until he reached the fourteenth degree twenty minutes[3], following the direction of the sunset. While the Spaniards were in the villages of the Urtueses and Aburunes, they saw many chiefs from the villages of the inland, who came to speak to the captain, brought him feathers similar to those of Peru, and plates of coarse metal (chapalone). He took information from them, and he asked them each one in particular about the villages and populations that were further on. » (Relation d'Hernando Ribera, in Commentaires d'Alvar Núnez, 489-490)

The density of culturally advanced populations increases as the small group of Ribera advances towards the foothills of the Central Andes. We even understand that the overwhelming numerical superiority of an Amerindian population so numerous and so concentrated in its villages hindered the exploration of Hernando de Ribera, who feared being captured :

« Hernando de Ribera also says that to the west he saw a lake so wide that from one shore to the other the land was not visible, that the shores were inhabited by very considerable populations who were dressed and rich in metal, and that they had very shiny stones with which they lined their fabrics; these Indians took these stones out of the lake. They had very large cities and the inhabitants were all farmers. They had food in great abundance. They raised many geese and other animals. From the point where the captain found the lake one could get to this lake and the people who lived there in a fortnight, without leaving a populated country, where there was a lot of metal and good roads when the waters were lowered. The Indians offered to take him there, even though he had only a small number of Christians with him, and the villages they had to pass through were large and densely populated. » (Relation d'Hernando Ribera, in Commentaires d'Alvar Núnez, 493-494)

The role of fermented beverages, particularly beer, is evolving within Native American societies which are differentiated both by their economies and social structures.

The carob tree beer is an occasional fermented beverage, next to mead, for the hunter-gatherer ethnic groups of the pampas. It is the beer of the southern summer (November-December). This seasonal beer cannot be part of the collective rituals celebrated throughout the year.

The cassava or sweet potato beers are becoming seasonal beverages among semi-sedentary Amerindian farmers, or even permanent fermented beverages as cassava and sweet potato are harvested all year round. They can be served with festivities and collective rites celebrated at any time.

The maize beer is brewed all year round with the grain reserves stored by the villagers living in more complex and hierarchical societies. This beer becomes a beverage that highlights the status of the caciques and chiefs in the strongly structured Amerindian societies such as those of the Gran Chaco and the Puna. Several kinds of beer were brewed within the same hierarchical Amerindian society, beers consumed according to social status. These contrasting situations can be seen in the stories of the European actors of the conquest.

The last stage in the evolution of Amerindian brewing was reached by the peoples of the Andean Cordillera, integrated into the Inca Empire. The local brewing traditions of the Amerindian farming communities are superimposed on the imperial management of the brewery in the service of the centralized power of the Incas and their allies. The Inca political power established rituals of offering maize beer (Sun, Ancestors), a beer-making service dedicated to the Inca's entourage, and a supply of grain and beer to messengers and troops throughout the empire. This political evolution took place several centuries before the arrival of the Spaniards. Their conquests would brutally halt this political and social evolution of the peoples in the Central Cordillera. By knock-on effect, the peoples of the Gran Chaco and the Puna lost the benefit of cultural influences from the Andean world in the 16th century.

The Amerindian Patagonia was not made up of centralised kingdoms or states like those that the Incas brought together within their empire. These horizontal societies without central political power nevertheless developed their own brewing tradition in a geographical environment with few plant food resources.