Your search results [5 articles]

Selling traditional beer among the Xhosa.

Yvonne Chaka Chaka, Umqombothi 2.0

Sharing beer in exchange for collective work is not the only way in which beer circulates among the Xhosa people. Traditional beers can be brewed for sale. This general phenomenon in Africa is the result of an adaptation to the commercial world, the increasing weight of the urban lifestyle and the changing economic status of women.

The Xhosa have two ways of selling traditional beer. The first derives from the sharing of beer for collective work. The imbarha are meetings where part of the brew is sold to clan members to raise money for collective works or projects (school, communal building, etc.). The second (inkazathi) takes the form of a freely organised drink by a group that decides to drink beer, collects what is needed to have it brewed by women and sells part of the brew to pay for the expenses incurred. These beer sales are not exempt from the social duty to give away a portion of the brewed beer, about a third, as gifts to people who are to be honoured or as part of customs that are to be respected (beer given to elders, clan or sub-clan leaders, etc.) (McAllister 239-242).

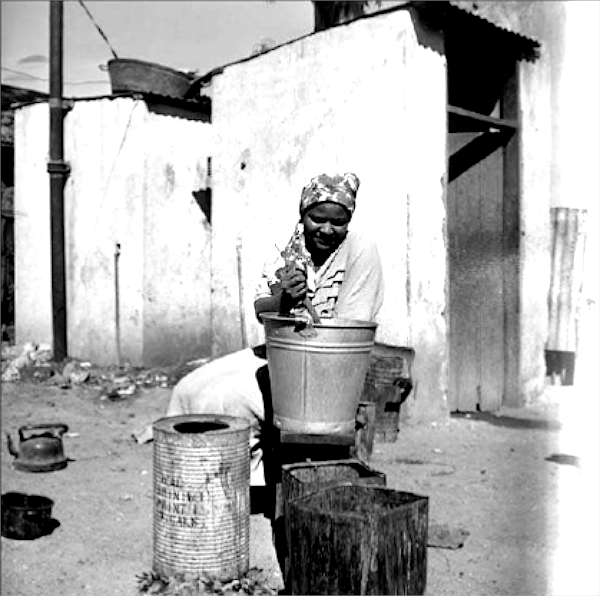

The mangumba beer is sold by women who need this means of subsistence (widows, isolated women). It is a beer based on industrial ingredients, quick to brew and more alcoholic. The brewer escapes two constraints. One is technical: brewing traditional beers requires at least 8 to 10 days of work, good quality corn and equipment. The beer must be drunk quickly. The other is social: the sale of mangumba beer can break the rules of reciprocity and sharing, especially in urban areas. The entire brew can be sold according to a market logic. Chemical additives preserve the beer[1].

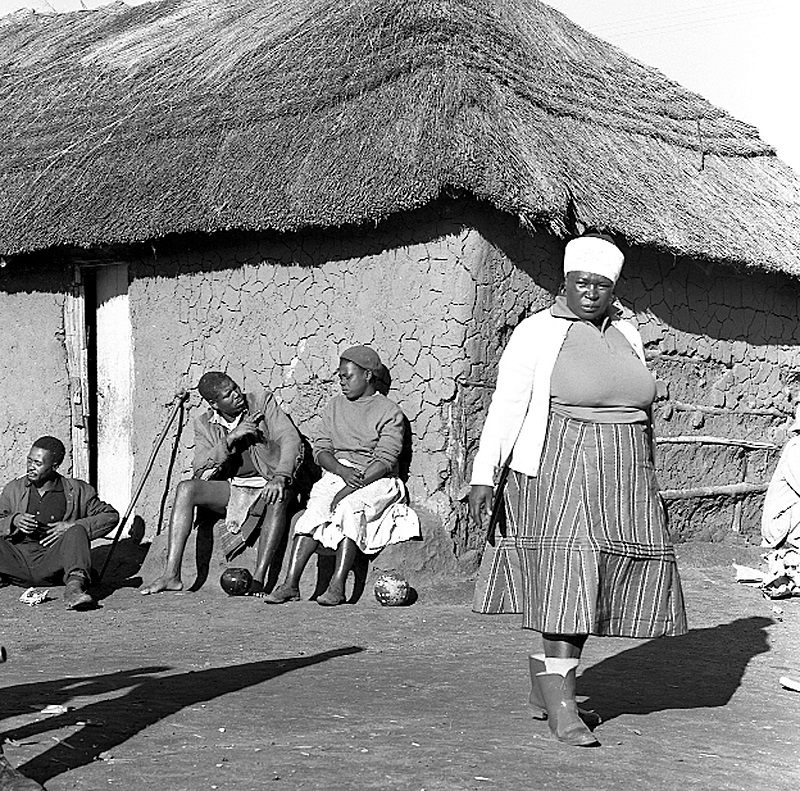

In 1927, South Africa passed the Liquor Act, which prohibited non-white South Africans from entering licensed premises or selling alcohol. The white minority forced the black majority to bury its age-old traditions and what forms part of its cultural identity and social cohesion. Clandestine beer bars are multiplying in the townships, run by courageous women-brewers-hostesses braving the repression: the shebeens or skokiaan queens. With the hardening of the apartheid regime in 1948, these underground bars became political meeting places and targets of the police. These township bars inherited in part the functioning of the Xhosa or Zulu beer sharing practices in their regions of origin: the central role of women, sharing beer in a domestic environment, brewing traditional sorghum or maize beers, etc.

|

|

|

| Skokiaan queen in Johannesburg (by Constance Stuart Larrabee, 1948) | Shebeen and beer bar in South Africa today | A Shebeen today and a beer bucket passing between drinkers |

[1] These pseudo-traditional beers are suspected of containing harmful substances in the same way as adulterated distilled spirits. In 2016, South Africa amended its Liquor Products Act of 1989 to define Traditional African beers more strictly.