Your search results [6 articles]

2 - The farmer-brewers of the Rio Paraná and Paraguay in the 16th century.

Two important sources let us know what the Amerindians of the Rio de la Plata drank and with what they brewed their traditional beers before the arrival of the Spanish expeditions on their coasts and rivers.

Two important sources let us know what the Amerindians of the Rio de la Plata drank and with what they brewed their traditional beers before the arrival of the Spanish expeditions on their coasts and rivers.

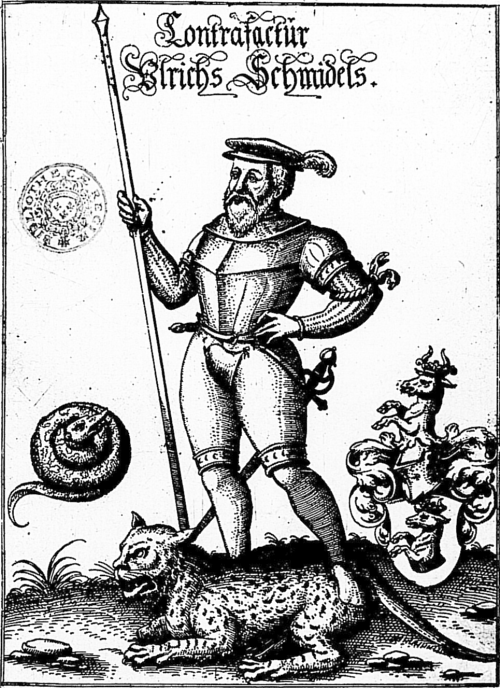

These are the Relation de voyage d'Ulrich Schmidel(Travel Report by Ulrich Schmidel) published in Nuremberg in 1599[1] and the Commentaires d'Alvar Núnez Cabeça de Vaca (Comments by Alvar Núnez Cabeça de Vaca) published in Valladolid in 1555[2].

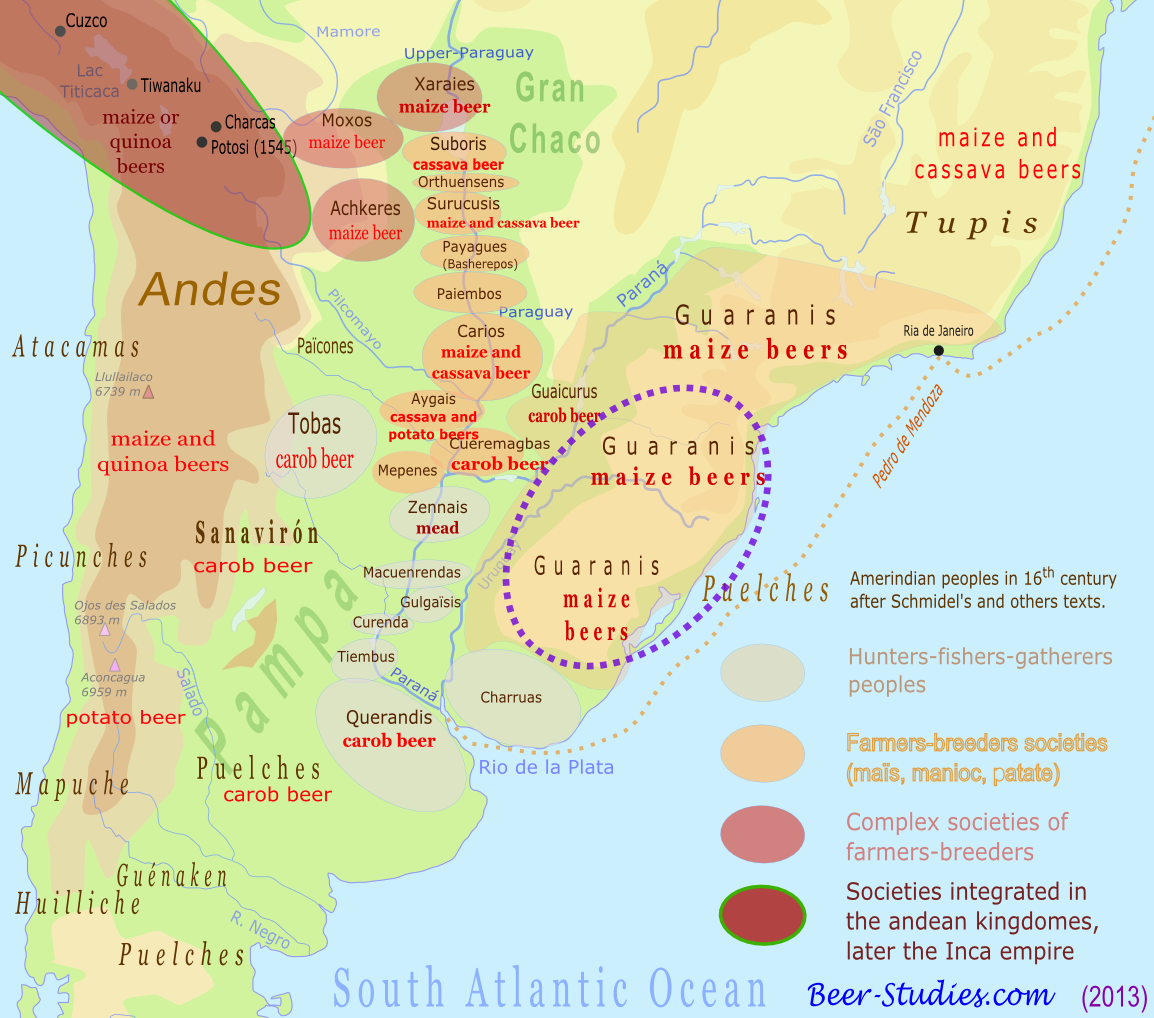

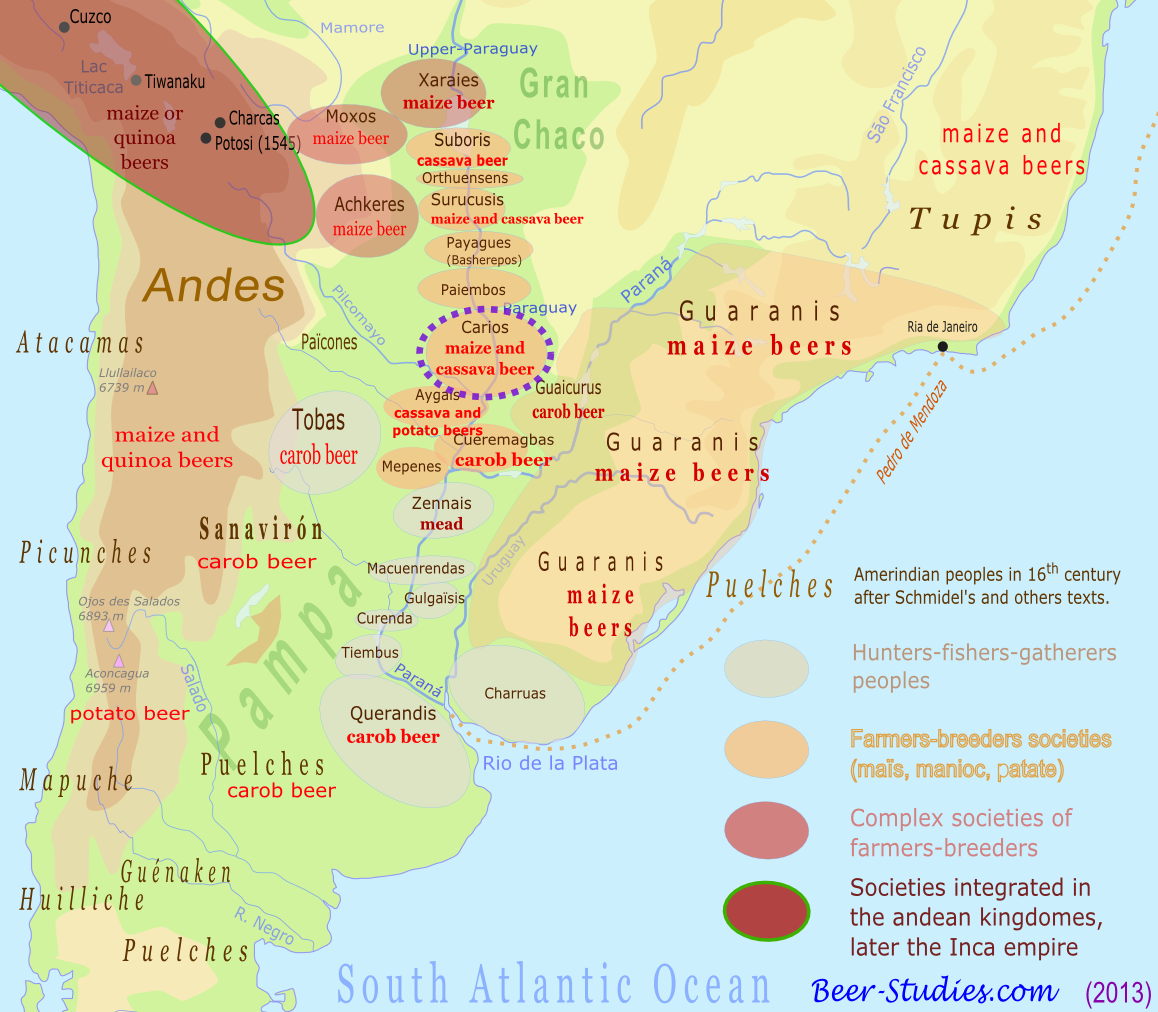

The chronology of these first conquests covers some twenty years, between 1535 and 1555. The Spaniards went up the rivers and approached Peru, more than 2,000 km between what is now the city of Buenos Aires (Argentina) and Santa Cruz de la Sierra (Bolivia). These journeys towards the North-West coincide with the encounter of peoples with increasingly complex social structures, until they reach the Andean foothills and the influence of the Inca Empire. We will try to verify whether, each time, beer adapted to this increasing social and political complexity in the Amerindian societies of the early 16th century.

The Amerindian societies that developed until the arrival of Europeans on the shores of Paraná and Paraguay did not all have the same way of life. Some are made up of semi-nomadic groups of hunter-fisher-gatherers. Others have reached the level of social complexity that accompanies the agricultural way of life, sedentary lifestyle, organisation into villages, and the existence of a social hierarchy. The latter societies store the maize grains, cassava tubers or sweet potato tubers that they grow. It is expected that these Amerindian societies not only know how to brew beer, but also how to give this fermented beverage a central social role. The Ulrich Schmidel's and Alvar Núnez's testimonies leave no doubt about this assumption.

The Amerindian societies that developed until the arrival of Europeans on the shores of Paraná and Paraguay did not all have the same way of life. Some are made up of semi-nomadic groups of hunter-fisher-gatherers. Others have reached the level of social complexity that accompanies the agricultural way of life, sedentary lifestyle, organisation into villages, and the existence of a social hierarchy. The latter societies store the maize grains, cassava tubers or sweet potato tubers that they grow. It is expected that these Amerindian societies not only know how to brew beer, but also how to give this fermented beverage a central social role. The Ulrich Schmidel's and Alvar Núnez's testimonies leave no doubt about this assumption.

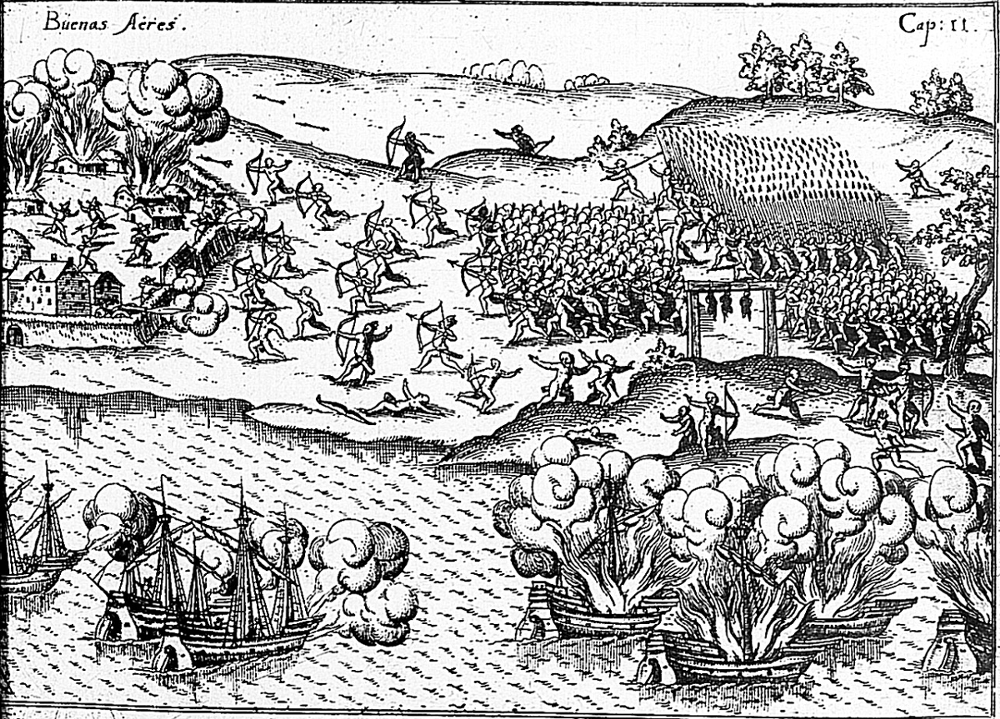

The armada[3] led by Pedro de Mendoza left the Spanish port of Cadiz and reached the Rio de la Plata in 1535. Schmidel, a German harquebusier and lansquenet, is on board with 150 other mercenaries from Northern Europe.

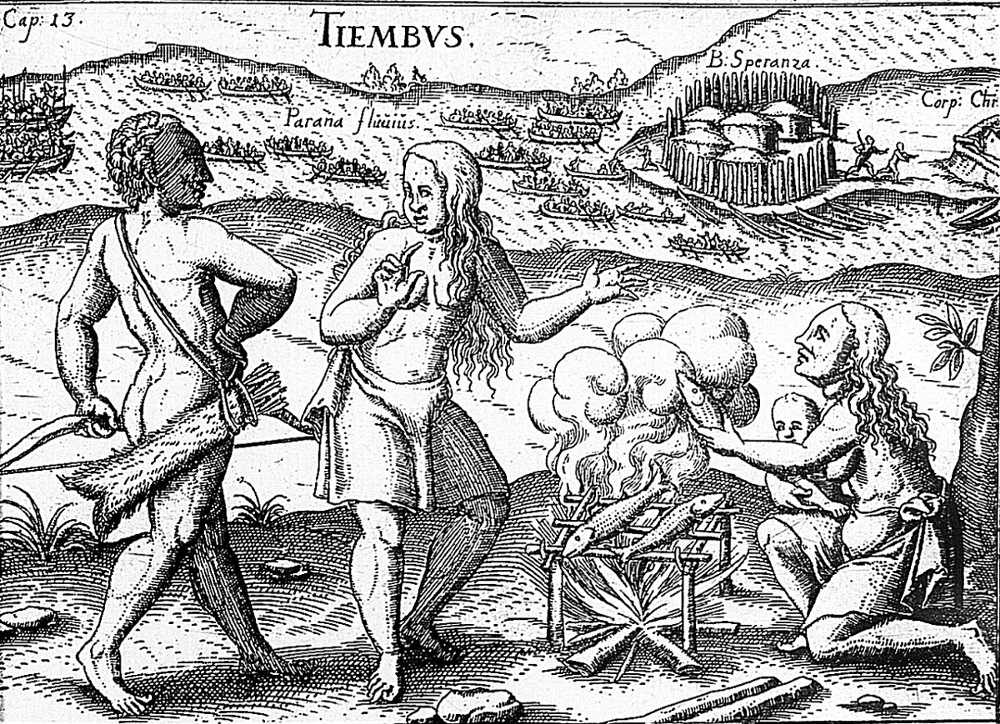

The Spaniards establish themselves by force on the territory of the Querandis who live in the estuary of Paraná. Their main village is conquered. The Spaniards baptise their own camp Nuestra Señora Santa Maria del Buen Ayre. There they starve for more than a year, not knowing how to fish or cultivate local plants, driven to starvation by the Querandis who practice a scorched earth policy[4]. What remains of the Spanish armada owes its survival to the Tiembus Indians, neighbours of the Querandis, forced and provisional allies of the new European comers.

The Spaniards establish themselves by force on the territory of the Querandis who live in the estuary of Paraná. Their main village is conquered. The Spaniards baptise their own camp Nuestra Señora Santa Maria del Buen Ayre. There they starve for more than a year, not knowing how to fish or cultivate local plants, driven to starvation by the Querandis who practice a scorched earth policy[4]. What remains of the Spanish armada owes its survival to the Tiembus Indians, neighbours of the Querandis, forced and provisional allies of the new European comers.

In 1539, a reinforcement of 200 Spaniards arrived from Spain at the Rio de la Plata. An expedition of 400 soldiers commanded by Juan de Ayalas decided to go up the Paraná River. Schmidel takes part in this expedition and tells the story of how the soldiers make sure that the people who live upriver will provide them with food supplies:

« So our chiefs made us board the brigantines again, and we started to go up the Parana to discover another river, called Parabol [Paraguay], which we had heard about: its banks are inhabited by the Carios Indians. We had been assured that we would find maize, fruit and roots, whose the natives make wine[beer], as well as meat, fish, sheep as big as mules, deer, wild boar, ostriches, chickens and geese in abundance.[5] » (Schmidel, Chap. XVI, Navigation en remontant le Parana jusqu’à Curenda, 69-70)

« So our chiefs made us board the brigantines again, and we started to go up the Parana to discover another river, called Parabol [Paraguay], which we had heard about: its banks are inhabited by the Carios Indians. We had been assured that we would find maize, fruit and roots, whose the natives make wine[beer], as well as meat, fish, sheep as big as mules, deer, wild boar, ostriches, chickens and geese in abundance.[5] » (Schmidel, Chap. XVI, Navigation en remontant le Parana jusqu’à Curenda, 69-70)

The "roots whose naturals make wine" refer to cassava or sweet potato. The "wine" refers in fact to beer. The European authors of the 16th century use wine as a generic term for all fermented beverages. The Carios live in the middle course of Paraguay and are among the Amerindian societies of the region (see map). Their farming villages are numerous and their granaries full. The soldiery draw from them shamelessly, sometimes after negotiation with the inhabitants, most often by force. The villages of the Carios brew beer all year round with maize or starchy tubers (manioc, sweet potato), the "roots" that Schmidel talks about in his whole story.

Alvar-Nuñez also notes that the Amerindian peoples settled in the upper reaches of Paraguay make a living from agriculture and have two annual harvests of maize and cassava. Puerto de los Reyes is the name given by the Spaniards to a settlement located far upstream from the city of Asunción, south of the Lago de los Xarayes, the Brazilian region of today's Pantanal:[6]

« The natives of the Port of the Kings [Puerto de los Reyes] are ploughmen; they sow corn and cultivate manioque, which is the cassava of the Indians. They also harvest a lot of mandubies [madubies, mandues, manduis = peanut], similar to hazelnuts. They have two harvests a year. » (Commentaires d'Alvar Núnez, 305)

Of course they brew maize and manioc beers. In January, the river floods the land. In 1543, the Spanish colony of Puerto de los Reyes is decimated by mosquitoes, fevers and diseases. Deprived of grain, one can imagine that instead of drinking beer, it was also forced to drink the contaminated water of the river, worsening its sanitary situation (Commentaires d'Alvar Núnez, 413-414).

The Guaranis Indians of the Yguatu river (25° south, now rio Jaurú), east of the Paraguay river are also farmer-breeders:

« According to the report of the natives (later it was discovered that this was true), many villages were to be found on its banks; the inhabitants are the richest in the whole region; the work on the land and the education of the poultry are the causes of this. They raise many geese, chickens and other birds; they have plenty of game, wild boar, deer, tapirs, partridges, quails and pheasants. The river is full of fish. They sow and gather a great quantity of maize, potatoes, cassavas, madubies [peanuts], and many other fruits, and the trees provide them with a great quantity of honey. » (Commentaires d'Alvar Núnez, 75)

This general agricultural prosperity favoured the Amerindian brewery. With several abundant sources of starch-rich plants, the Amerindian peoples of the region developed a rich brewing tradition. Their social life and the rivalries between them also fostered, as we will see, celebrations, collective drinking and the search for ritualized drunkenness.

As soon as these boats were built and equipped, our general gathered his troops, and sent them off with three hundred and fifty men, under the command of George Luxan, to whom he gave the order to go up the river, and to seek food from the Indians [this means plundering their villages]. But the Indians, having been warned of our arrival, thought that the best way to get rid of us would be to burn their villages, their provisions, everything that might be of use to us, and withdraw inland [far from the rivers on which the brigantines sailed]. We could not find food anywhere. Only three and a half ounces of flour was distributed to each man a day, so that on this journey half of our companions died of hunger." (Schmidel, 47-48). We understand that the death of the troops was caused by the improvidence of the Spaniards and general incompetence, more than by the aggressiveness of the so-called "savage Indian tribes" who preferred to flee to protect their women and children.