The fermented beverages of the Central Asian nomads

The fermented beverage drank during the warm season is called koumis (Turkish qïmiz/qumiïz, Mongolian aïrag), the fermented mare's milk containing 3%-4% alcohol. It is made after the parturition of mares. William of Rubruck describes the process in detail : [1]

« Here's how the comos [koumis] is made, that is a milk of mare: they tend a long rope above the ground between two stakes driven into the ground and they attach to the rope, around the third hour of the day, the foals of mares from whom they want milk. Then, the mothers stand near their foals and give milk without difficulty : if one of them is too rebellious, a man takes the foal, lets it suckle the udder, then withdraws the foal and let the place to the responsible for milking. When they have got a lot of milk - it is as sweet as cow's milk when it is fresh - they pour it into a large goatskin or other container and begin to beat the milk with a stick for this purpose, with a thick base as a man's head and a hollow underneath. They beat milk as quickly as possible, so it starts to boil like the new wine and to sour or ferment. And they beat it until they have extracted the butter. Then they taste it, and when it is a little pungent, they drink it. At this very moment, the prickle on the tongue is like that of a rough wine; and after drinking, (the koumis) leaves in the mouth a flavor of almond milk; it greatly rejoices a man's heart, and even intoxicates the weak heads. It is very diuretic. » (Rubrouck 85).

5-8 milkings per day give 4-5 liters of fresh milk for each mare. The milking of mares and the making of koumis are men business, the milking of cows and the making of cheese, yoghurts, creams are women's affairs. The summer means plenty of koumis / aïrag. The large goatskin of 100-150 liters, daily filled with fresh skimmed milk, beaten, is always hung at the entry of the yurt

There is a koumis reserved for the circle of the Khans (Mongol chieftains, and of course the Khan emperor itself), the kara koumis (black koumis). The milk comes from the milking of the imperial herds.

« They also make some caracomos [kara koumis], that is to say a black comos for the use of lords, as follows. Mare's milk does not curdle : it is a fact that there is no milk curdling if we do not find curdled milk in the fetal stomach. In the stomach of foals, one cannot find it, so the mare's milk curdles not. This is why they beat the milk until all the thick contained substance gets to the bottom, like the dregs of wine: what is clear stays above and resembles whey or white must. The "dreg" is very white : it is for slaves and make sleeping much. As for the clear liquid, only masters may drink it : this is certainly a very mild drink which has beneficial properties. »

The khans and the chieftains of mongol hordes have their own herds to get the kara koumis. In addition, each farmer of a clan must bring to his chieftain a third of his own milkings. There is here a social mechanism similar to that of collecting and redistributing grains inside the farming societies.

French documentary on Arte TV 2004, Gengis Khan, Cavalier De L' Apocalypse. Extract about the airag, fermented milk from mare, its importance for the diet of herders and the social life under the Mongolian yurt (airag sequence at 0:42).

In the winter, after the "letting go of the mares" (stop of milking) in the fall, a fermented drink made from grains takes over the koumis. The southern Turks and Tartars, although semi-nomadic, need to establish seasonal links with the sedentary peoples settled in Central Asia, farmers and beer drinkers. They barter their own products coming from hunting and cattle breeding for agricultural products and handicrafts. Cheese cons grain, animals skins cons tissues, etc. Provided with grains, the semi-nomads peoples know how to brew beer, albeit in a seasonal manner.

« In winter, they make an excellent drink from rice, millet, wheat, honey, clear as the wine. The wine is imported from remote areas. In summer, they only drink comos. There is always some comos in the front part of the house, near the door, and beside stands a zither player with its small instrument. » (Rubrouck, 83).

At the onset of the winter of 1253 in the steppe, the modest William's caravan, with a view of the Alatau Mountains, oblique to the south towards Kyrgyzstan :

« In the Octave of All Saints [Nov. 8], we entered into a city inhabited by Saracens, named Kinchat. Its captain came out of the city to meet our guide, with some cervoise [2] and cups. Indeed, it is the usage that from all the cities they have, one comes out with food and drink to meet the messengers of Batou and Mangou-chan (Möngku-Khan) ... A great river flowed out of the mountains; which watered the whole region, and it sufficed to direct its waters at will. This river did not flow toward any sea, it was absorbed by the earth and formed also many marshes. There I saw vineyards and drank wine twice. » (Rubrouck, 124).

This river is named Talas. It irrigates a fertile valley. The beer from grains (rice and wheat in the plains, barley and millet in mountainous areas) coexists here with the wine from grape.

« Then they brought us some drinks : it was a cervoise from rice, a red wine similar to a wine of La Rochelle, and comos. Then the lady a cup in hand, bent knees, asked the blessing, all the priests sang in full voice, and she emptied the full cup. » (Rubrouck, 261).

« Many people came to visit our guide, the cervoise from rice was brought to him in long bottles with a narrow neck. I could not in any way discern this (cervoise) from the best wine of Auxerre, except that it did not smell wine. » (Rubrouck, 141).

During his trip eastward, William drinks also a beer from glutinous millet when he reaches the vicinity of the Mongolian imperial court, and enters the area of the Chinese cultural influence.

« We arrived at our cold house, and devoided of everything. Beds and blankets were provided, one also brought what to make fire, we have been given the meat of a small and skinny sheep for the three of us, which should feed us for six days, and a daily ration of one bowl of millet and a quarter of cervoise from rice a day. » (Rubrouck, 153).

The Chinese called this beer huang jiu, the "Yellow beer". This kind of beer seems to be here a second category beverage, if we take in account the precarious treatment that the Mongols have given to both monks and their guide.

In 1245-1247, the Franciscan Plancarpin confirmed that the Mongols (those he called Tartars) « drink a lot of mare's milk, but also, when available, sheep's, cow's, goat's and even camel's milk. They have no wine, beer or mead, unless it is supplied or offered by other nations. » (Jean de Plancarpin 2014, 86)[3] . The grain bartered with neighbouring farming peoples feeds the Mongols in the winter, the season of lean grazing, and makes up for the lack of milk and koumis with millet soups and beers:

« In winter, unless they are rich, they do not even have mare's milk. They cook millet with water, so much so that the result is a dish that is drunk more than eaten, and each of them drinks a cup or two in the morning and eats nothing else for the rest of the day; » (ibid).

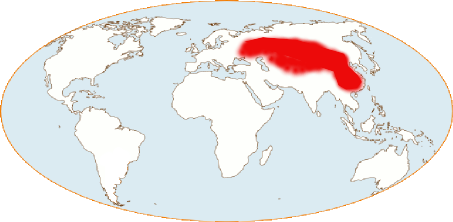

This essential complementarity of pastoral and agricultural economies is a key factor in understanding the way of life of the peoples of Central Asia.

Plancarpin points out that the Mongols « consider it quite honourable to get drunk: they drink a lot and vomit just as much, which does not prevent them from drinking again. » (op. cit. 85)

As a provisional conclusion, the Asiatic nomads, though pastoralists and transhumant, do know the secrets of beer brewing, since ancient time. A food product of their own and specific of their lifestyle embodies the combination of grains and dairy products. This is the fermented butter. Some milk from cow or mare, from yak in Tibet, is heated to extract the butter which is then mixed with flour of barley or millet. It is let aside to dry and become rancid. This hardened butter-flour keeps well all winter. It will provide lipid and starch during the cold season.

[1] Rubrouck Guillaume de, Voyages dans l'Empire mongol, 1253.-1255. Translation and comments by Claude-Claire and René Kappler. Imprimerie nationale Editions Paris, 1993, 2007.

Rubruck's travel account in english ⇒ William of Rubruck's Account of the Mongols

[2] The french word "cervoise" translates the Latin word "cervisia" wisely chosen by the very scholarly Franciscan monk in his report written in Latin. Rubruck gives this name to the Mongol fermented beverage he has tasted (it is a beer indeed), instead of the classical Greek and Roman paraphrases "rice wine" or "barley wine". William is Flemish and was immersed in the beer culture during his youth in Rubruck, a village that is now close to the border between France and Belgium. He writes "cervisia de millio" (and not "vinum de millio") when he speaks of the millet beer drank in Karakorum, capital of the Great Khanate.

[3] Another European travels to Karakorum in 1245-1247 : Giovanni da Pian del Carpine (Giovanni born in Pian del Carpine, in Ombria, Italy). See Histoire des Mongols, translated and annotated by Dom Jean Becquet and Louis Hambis. Paris, Adrien-Maisonneuve, 1965. Plancarpin was a Franciscan friar and Pope Innocent IV's legate to the Mongols to negotiate an end to the attacks on Christianity. The mission fails. Jean de Plancarpin. Dans l'Empire mongol - Textes rassemblés, présentés et traduits du latin par Thomas Tanase - Anacharsis 2014.