Your search results [3 articles]

How the Songola people brew their beers.

Unhusked rice (mùfùngà), maize (ìsàngû), and cassava (môsôngy) are prepared separately. The Kuko women regard rice as indispensable for fermentation whereas maize is often omitted. On the contrary, Enya women, having only small fields, often omit rice because unhusked rice is much more difficult to find at the markets than maize. The production is done exclusively by women. The men usually mix and sell the liquor which their wives have made.

The entire beer making process consists of 4 phases:

- The making of the rice ferments (beer starter).

- The preparation of maize malt on which mycelium is grown.

- The cooking of the cassava paste.

- The proper brewing.

The technical diagrams have been drawn by Takako Ankei, and the photographs taken by her.

A. - T. Ankei divides the preparation of rice and beer ferments into 11 steps.

It includes the making of beer ferment pellets, the technique we are interested in here.

- Rice, harvested in February- April, is stored in the form of bundles of ears, and is sometimes stored in a tin as threshed grains before the cropping seasons. Threshing is done by treading the bundles.

- Unhusked rice grains are put in a mortar (kilùngà) and are roughly crushed with a pestle (mùtùti).

- Water is poured on the mixture of the husked rice, bran and husks until it becomes wet and homogeneous.

- The wet mixture is put in a food basket (kitutu) lined with tree leaves, and the content is covered with the same leaves. Trees having large leaves are chosen: Vernonia conferta Benth. (Compositae, Songola name mùbângàlàlâ) and Caloncoba welwitschii (Oliv.) Gilg (Flacourtiaceae, kilûmbûlûmbù ki mùkàli). These leaves, used especially for this purpose, have hairy surface whereas the leaves of Marantaceae herbs, usually used for wrapping foods, have a smooth surface.

- The basket containing 20-30 liters of wet rice is stored at a dark corner of a bedroom or a storeroom. On the fifth- or sixth-day, molds are observed to cover the pounded rice, and the Songola say that at this stage there is already the trace of the specific smell of alcohol. Molds are called lùbùngi by the Songola. The Songola includes in this term the molds growing on any other foodstuffs and also the dense fog from the Congo River.

- On the tenth to sixteenth day, the mixture of rice, transformed into small lumps by molding, is pounded carefully in a morter with a pestle.

- The pounded mold-fermented rice is wrapped with the leaves of the trees as in the stage 4, and is put in a basket. It is hen placed on a shelf called kiliyâ, over the hearth. After three days, the content becomes completely dry.

- The dry content is pounded again.

- The result is now made to pass through a sieve kàyùngi on a shallow and wide basket lùèlì. Grey powder is obtained as the product of these processes.

- This powder is covered with the leaves as in the processes 4 and 7. This product is called vyambo in Swahili, a word that usually means baits for fishing or baits in a trap for animals.

- The basket is stored on the food shelf until all is ready for the start of mixture and brewing.

B. - T. Ankei divides the preparation of maize malt into 9 steps.

A critical process as well, because the malted and still wet maize is wrapped into tree leaves to be put in a molded state. Maize is always used to supplement rice among the Kuko whereas it is sometimes used independently among the Enya. The preparation of the maize is is practically the same as that of rice. The difference is that it is made to sprout before molding.

Maize is twice harvested in December- January and in April-May (Ankei, 1981). Although younger soft ears of maize are cooked, the mature kernels are exclusively used for brewing. 2. The ears are shelled. Unlike rice, the kernels are not crushed. 3. The kernels are soaked in water for two or three days. 4. The soaked kernels are wrapped in the same leaves as in the preparation of rice, and are put in a basket. 5. The basket is placed in a dark corner of a bedroom or a storeroom for three days while the kernels germinate. 6. The germinated kernels are crushed in a mortar. 7. The crushed kernels wrapped in the leaves become covered with molds, and after several days, the smell of distilled liquor begins to become evident. 8. The mold-covered kernels are beaten again in a mortar, but are not made to pass through a sieve, as is the case with rice. 9. The product, also called vyambo, is stored separately from rice in a basket on the food shelf.

- Maize is twice harvested in December- January and in April-May (Ankei, 1981). Although younger soft ears of maize are cooked, the mature kernels are exclusively used for brewing.

- The ears are shelled. Unlike rice, the kernels are not crushed.

- The kernels are soaked in water for two or three days.

- The soaked kernels are wrapped in the same leaves as in the preparation of rice, and are put in a basket.

- The basket is placed in a dark corner of a bedroom or a storeroom for three days while the kernels germinate.

- The germinated kernels are crushed in a mortar.

- The crushed kernels wrapped in the leaves become covered with molds, and after several days, the smell of distilled liquor begins to become evident.

- The mold-covered kernels are beaten again in a mortar, but are not made to pass through a sieve, as is the case with rice.

- The product, also called vyambo, is stored separately from rice in a basket on the food shelf.

C. - T. Ankei divides the cooking of cassava paste into 7 steps.

The cassava flour (lôpôtô) is prepared from bitter cultivars (mosongy wàchywâ). The tubers are soaked in water in order to dissolve the poisonous cyanide contained in them. The process is the same as that of the preparation of bùkâlj (ugali in Swahili), one of the staple foods of the Songola.

Bitter cassava is peeled, to get rid of the most poisonous parts of the tubers. 2. Peeled tubers are soaked in a shallow pool near the fountain in the forest for about three days. The sodden tubers become soft when the poison is dissolved out. They are put in baskets and are carried back to the village. 3. The sodden tubers are put in a mortar and pestled. Hard, wick-life cores are removed. 4. The beaten tubers are rounded into balls with a diameter of 15-20 centimetres. These balls are called kimùndà ki mosôngy. 5. The cassava balls are dried on a food shelf. It takes about four days until they are dry. 6. The dry cassava balls are beaten in a mortar. 7. The content of mortar is passed through a sieve in a shallow basket to obtain fine bitter cassava flour (lôpôtô).

- Bitter cassava is peeled, to get rid of the most poisonous parts of the tubers.

- Peeled tubers are soaked in a shallow pool near the fountain in the forest for about three days. The sodden tubers become soft when the poison is dissolved out. They are put in baskets and are carried back to the village.

- The sodden tubers are put in a mortar and pestled. Hard, wick-life cores are removed.

- The beaten tubers are rounded into balls with a diameter of 15-20 centimetres. These balls are called kimùndà ki mosôngy.

- The cassava balls are dried on a food shelf. It takes about four days until they are dry.

- The dry cassava balls are beaten in a mortar.

- The content of mortar is passed through a sieve in a shallow basket to obtain fine bitter cassava flour (lôpôtô).

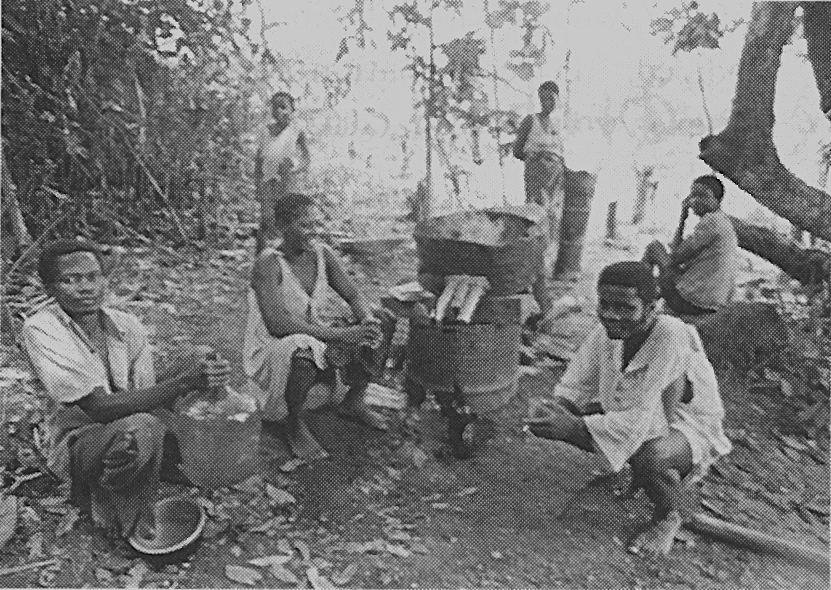

D. - T. Ankei divides the brewing proper into 6 steps.

The mold-fermented rice (A) and/or germinated and mold-fermented maize (B), and cassava flour (C) are mixed with water to form the mash in which the alcoholic fermentation takes place. The Kuko prefer rice to maize and will not make alcoholic beverages without rice. It takes ten to sixteen days for the preparation of rice and maize, and seven days for cassava flour. The Songola say that rice and maize stand by until the cassava balls are dry. Preparation of the mash is carried out in an open space beside the water. This kiwanja ki màly, or an open space for liquors, is generally situated in the bush not far from the village. The following fermentation and consequent distillation take place in this open space.

Water is boiled in a big metal pot. The cassava flour prepared in stage C-7 is poured gradually into the boiling water. 2. The content is kneaded with a long spatula (mùlûwà) to make a sticky hot cassava paste, bùkâlì. 3. The hot cassava paste is spread directly on the ground until it gets cool enough to be touched with hands. This warm cassava paste is returned to the same pot. The cooling process is followed very carefully because the consequent fermentation will fail if the paste is too hot. 4. The cassava paste is mixed with rice and maize powder. One part rice (and/or maize) powder is poured on 2-3 parts cassava paste and the result is carefully kneaded by hand until the mixture becomes homogeneous. 5. The contents is put in an open drum can (ngùngùlù), and is tightly covered with banana leaves (kàânì). 6. After seven to twenty days, the mixture in the drum is ready to be distilled. When the fermentation is completed, the paste becomes soft and fluid. The interval from mixing until distilling can be controlled by the thickness of the cassava paste in stage D-2: soft cassava paste (bùkâlì byâ tèmbà) takes less time than a stiff paste (bùkàâlì byâ nùnâ).

- Water is boiled in a big metal pot. The cassava flour prepared in stage C-7 is poured gradually into the boiling water.

- The content is kneaded with a long spatula (mùlûwà) to make a sticky hot cassava paste, bùkâlì.

- The hot cassava paste is spread directly on the ground until it gets cool enough to be touched with hands. This warm cassava paste is returned to the same pot. The cooling process is followed very carefully because the consequent fermentation will fail if the paste is too hot.

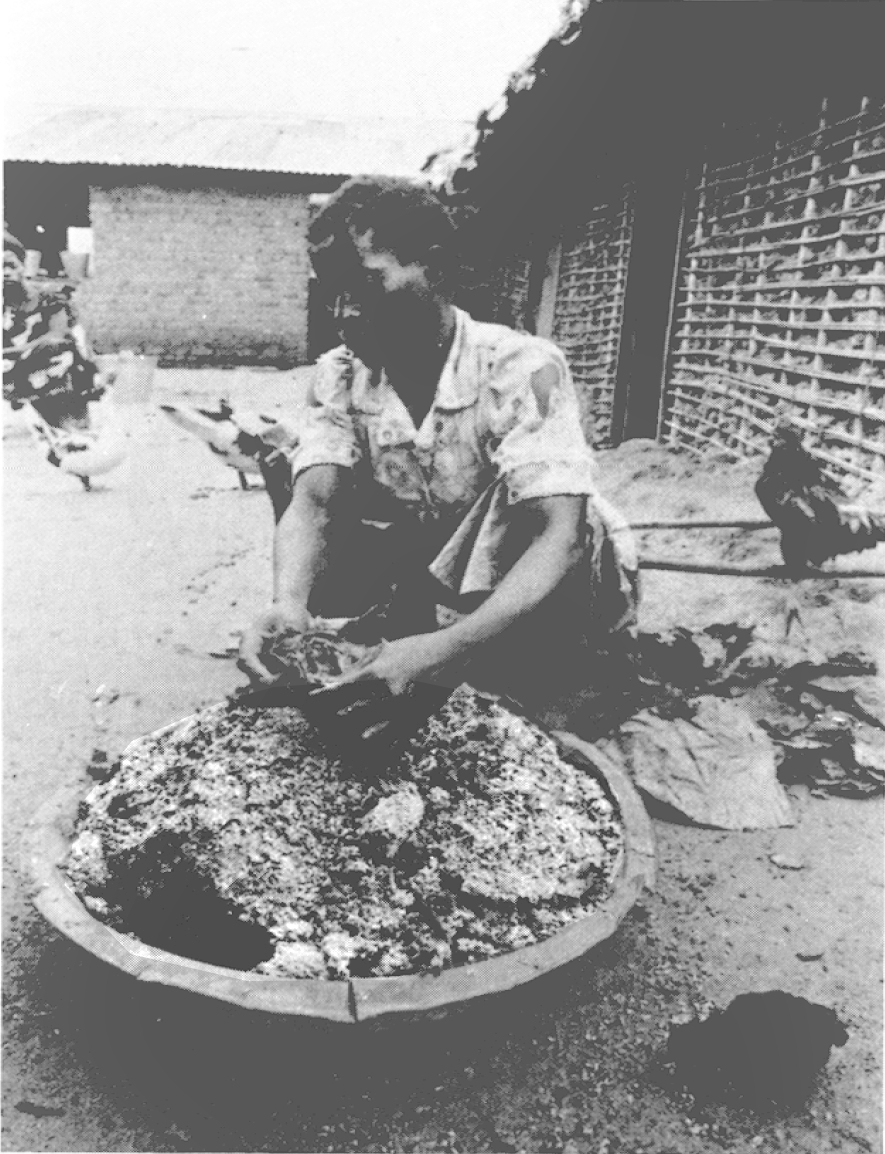

- The cassava paste is mixed with rice and maize powder. One part rice (and/or maize) powder is poured on 2-3 parts cassava paste and the result is carefully kneaded by hand until the mixture becomes homogeneous.

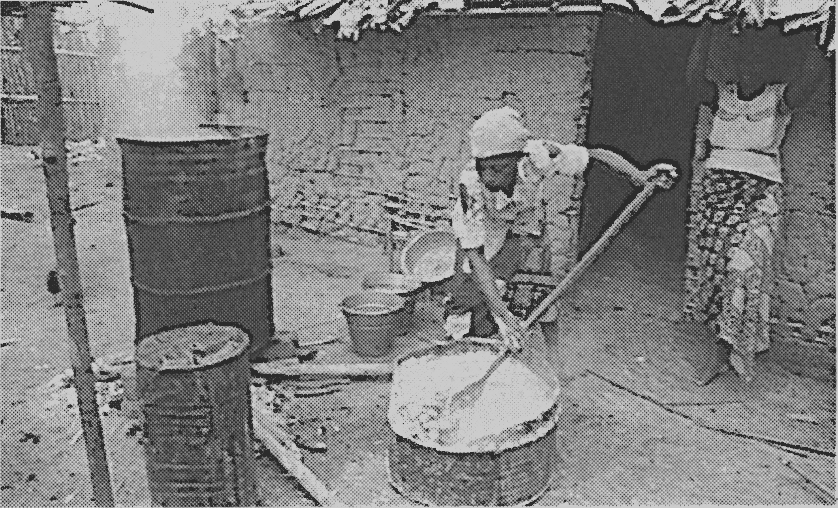

- The contents is put in an open drum can (ngùngùlù), and is tightly covered with banana leaves (kàânì).

- After seven to twenty days, the mixture in the drum is ready to be distilled. When the fermentation is completed, the paste becomes soft and fluid. The interval from mixing until distilling can be controlled by the thickness of the cassava paste in stage D-2: soft cassava paste (bùkâlì byâ tèmbà) takes less time than a stiff paste (bùkàâlì byâ nùnâ).

We are only referring to distillation. Ankei devotes several descriptions to it as she has found that the Songola give it time and resources. For Ankei, distillation is the fifth and final phase of brewing. The evolution from fermented beverages to distilled spirits is a significant trend in Africa and other continents, and is relatively recent (two to three centuries) compared to the multi-millennial history of traditional beers.

Distillation responds to several "needs": the taste for more alcoholic beverages, alcohols that can be preserved (a traditionnal beer must be drunk within 2-3 days), and alcohols that can be sold and bought. These new needs are the consequence of the upheavals suffered by traditional African societies: social destructuring resulting from an often brutal colonisation, the introduction of European distilled spirits around the 17th century, the slow spread of the western merchant world and its own social-economic rules (buy/sell rather than exchange/share, individualised work for wages and no longer collective work for beer and food, etc.).