Your search results [3 articles]

Takako Ankei's discovery and its significance for the geography of beer.

Implications for the geography of beer in Africa:

Along with the munkoyo beer brewed with amylolytic plants, the Songola beer brewed with amylolytic ferments makes it possible to divide the geography of traditional African brewing into several zones, as many as different techniques covering more or less different categories of starch resources: ancient African cereals (sorghum, millet, eleusine), Asian plants (taro, yam, plantain), new Amerindian cereals (maize, cassava, sweet potato), tubers, starchy fruits (plantain). An evolving and more complex geography. It should be noted that there are probably other African regions using this amylolytic beer ferment technique (Iraqw from Tanzania, etc.).

Implications for the geography of beer in the world:

This discovery of a new brewing technique in Africa echoes similar findings in South America. Terry Henkel documented in 2004 the actual brewing of cassava-based parakari beer by the Wapisiana Indians of Guyana. A strong variety of cassava-based cachiri is brewed in this way by the Wayana Indians of Guyana and Surinam. It is a remarkable brewing method because it can be adapted to all sources of starch (tubers, cereals, grasses, beans, carob seeds, ...).

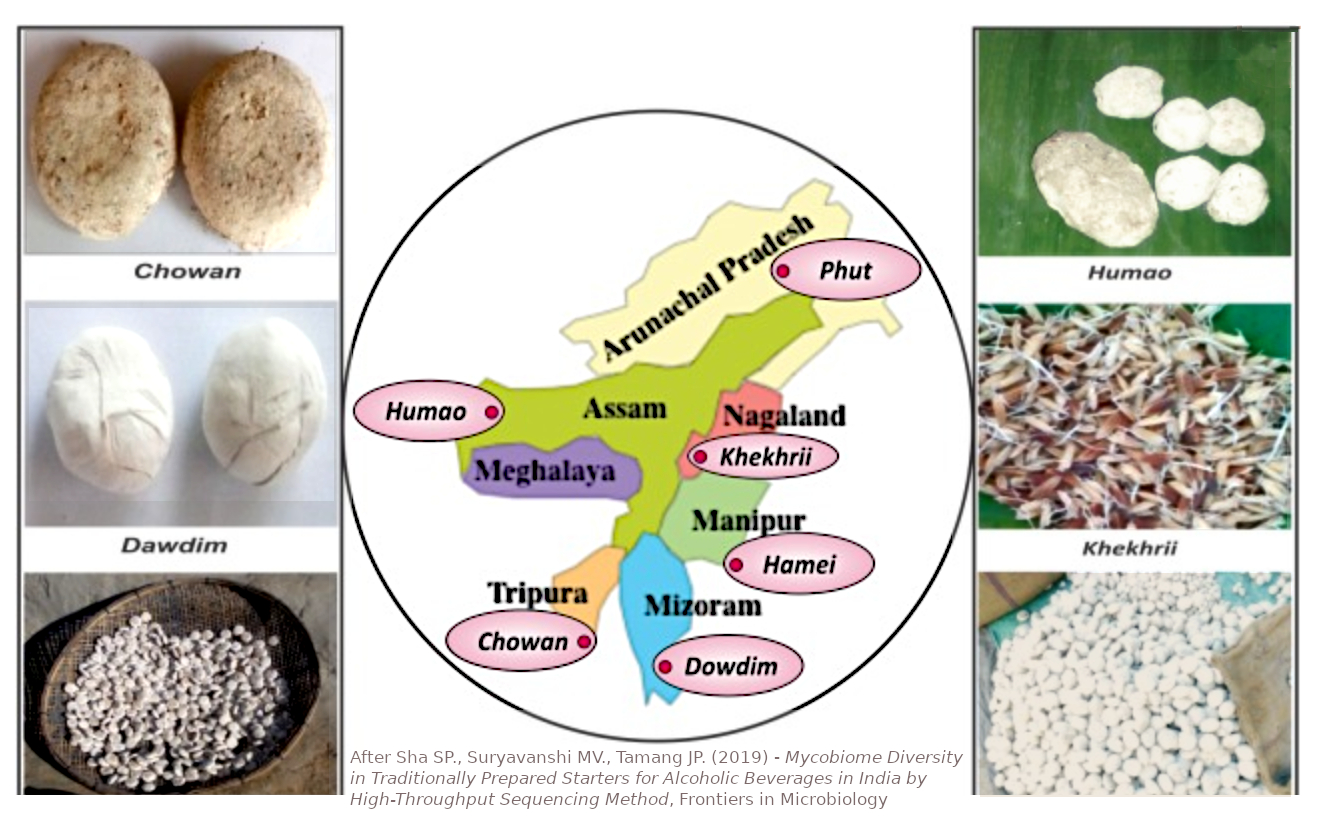

These ferments have been used to brew beer in India for 3 millennia. They are used today in north-eastern India in the states of Arunachal Pradesh, Assam, Meghalaya, Nagaland, Manipur, Tripura, Mizoram by predominantly non-Hindu populations (Sha & al. 2019). They are also found in the Himalayan foothills in Nepal, Sikkim, Bhutan, and Uttar Pradesh.

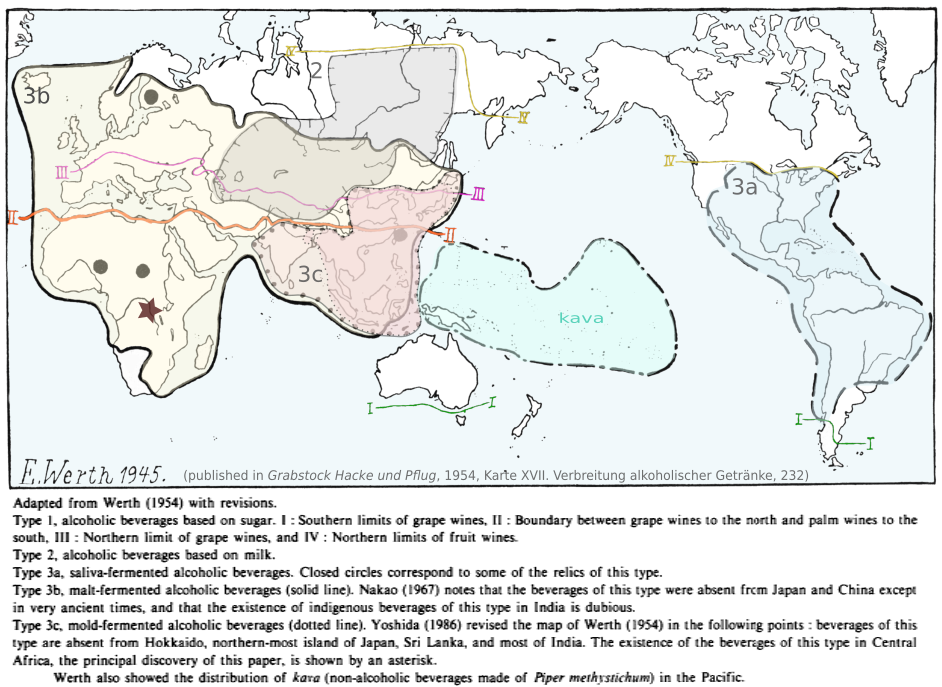

T. Ankei, relying on a general map of fermented beverages drawn up by Emil Werth in 1954 and revised by Yoshida in 1986, has positioned her own discovery of beer ferments in the heart of Africa. This simplified map shows that brewing techniques are not specific to each continent: malting for Europe, beer ferments for Asia, insalivation of manioc or maize for America, etc. It is more likely that all brewing methods (6 in all) were used on all continents. The most recent discoveries (archaeological or ethnological) support this view. Each continent has explored all possible ways of brewing beer. Some of these methods are still practised where they were not expected, as shown by the discovery of T. Ankei in Africa or that of Henkel in Guyana. Werth's map of fermented beverages is oversimplified, too simplified to show this wealth and dispersion of the brewing methods on a global scale. Drawing a new, up-to-date and more accurate map is a long-term undertaking.

The introduction of Asian and then Amerindian starch plants in Africa had an impact on its local brewing techniques. As a result, these indigenous techniques, too often presented as fixed and primitive since the dawn of time, have continued to evolve. These developments have followed the various routes of diffusion of these plants within the African continent. This immense subject is barely touched upon in historical studies of African brewing.

T. Ankei has attempted to reconstruct some of these developments through the ways in which cassava is prepared and consumed. She reached the following conclusions based on previous work and her own knowledge of Songola cooking and brewing methods (Ankei 1996) :

- There are at least 5 different routes by which the various cassava species arrived in Central Africa and were adapted to local culinary methods. Through the Kongo and Angola kingdoms (around 1590), the introduction has split into 2 routes: one up the Congo River (route no. 1), the other across the savannah further south (route no. 2). The Zanzibar route (around 1800) brought cassava to the Great Lakes region, Lake Tanganyika and then to the rainforest (route no. 3). The Mozambique route (around 1750) goes up the Zambezi to Lake Malawi (route no. 4). Cassava was adopted later in West Africa via a 5th route taken by slaves returning from Brazil in the 19th century (route no. 5).

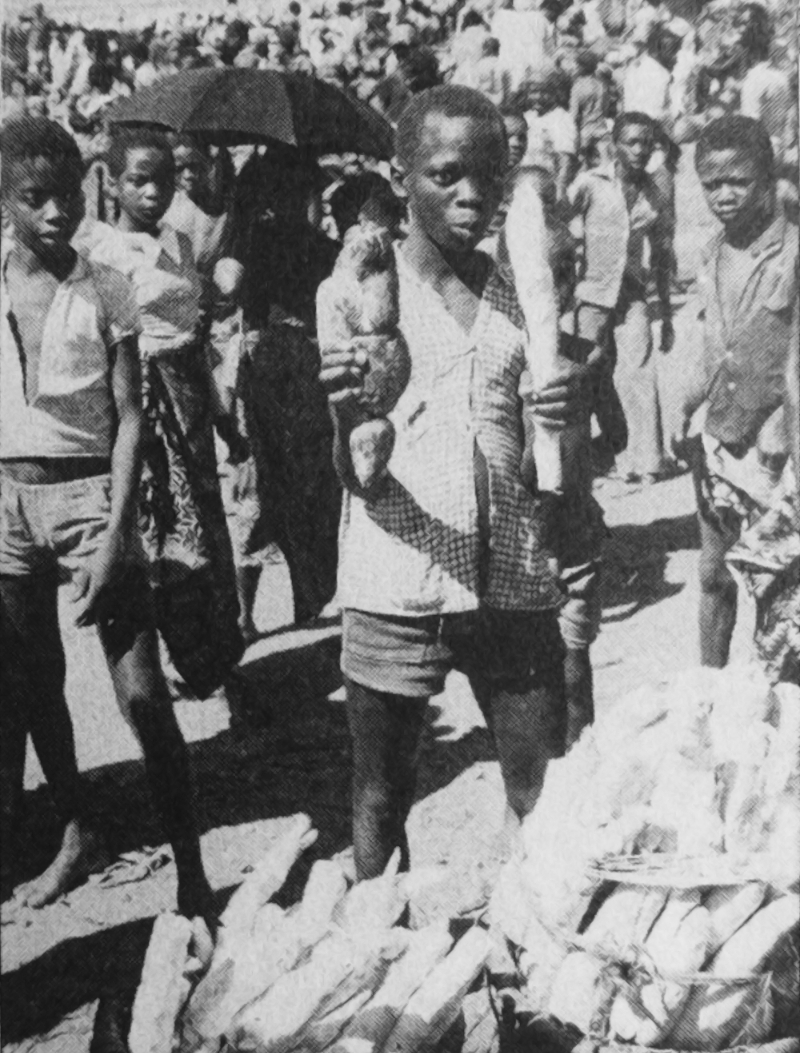

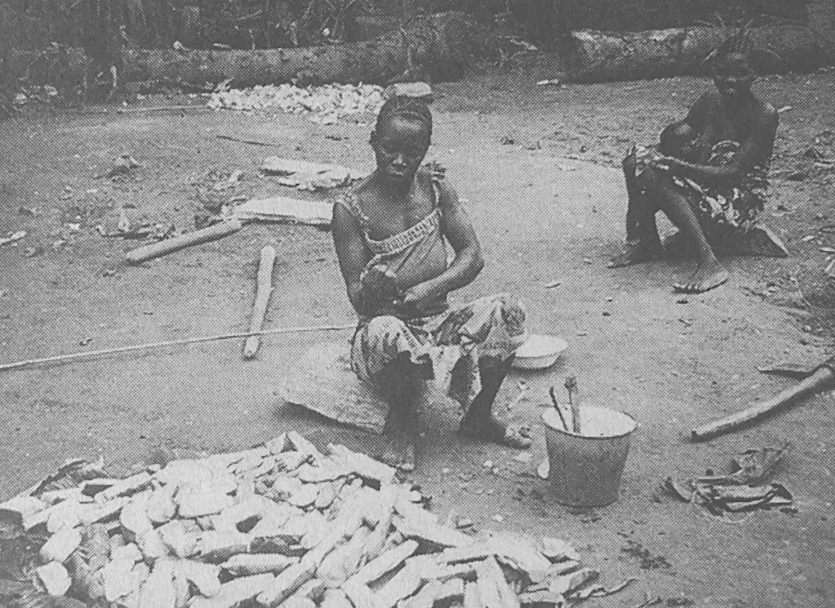

- Route no. 1 is that of bitter cassava by retting (soaking in running water and fermenting) then formed into sticks wrapped in leaves (with or without smoking): kwanga of the Bakongo or ki.kwanga of the Songola.

- Route 2 is that of bitter cassava detoxified by retting, then dried and ground into flour.

- Route no. 3 brings a specificity: the preparation of cooked bitter cassava pods by fermentation and soaking in standing water, thus without retting. The fermented cassava pods sold on the shores of Lake Tanganyika are part of this heritage.

- The Songola have a variant of the three methods of preparing bitter cassava mentioned above: retting-fermentation, fermentation without retting, cassava flour. The Songola and neighbouring peoples are thought to be at the crossroads of several cassava distribution historical routes (nos. 1, 2 and 3). In addition, they mix the bitter cassava paste with other plants (plantain, yam), a custom of the rainforest peoples.

Can these elements help to clarify when and how the Songola adopted or invented their method of brewing with beer ferments? At least since the Kwanga cassava sticks were brought up the Congo River in the 16th century. Asian rice cultivation does not seem to have preceded cassava cultivation on the upper Congo River. Cassava, not rice, would have been the carrier of this innovation for brewing beer. The hypothesis of an indigenous invention cannot be excluded. Yams and other starchy tubers of Asian origin such as taro arrived in tropical Africa two to three millennia ago. They may have served as a medium for the cultivation of amylolytic fungi specific to the ecosystems of the African rainforest and may have modified the brewing techniques of the peoples of the region, the Pygmies in that time. Some plants with starchy fruits or bulbs native to the rainforest (e.g. Gilbertiodendron dewevreii) may have played the same role, this time without involvement of plants of Asian origin.

Sources and bibliography:

Ankei Takako (2002), Alcoholic Beverages in Africa South of the Sahara: A Memorandum on Local Brewing Technology. Journal Of The Brewing Society of Japan, 2002 Volume 97 Issue 9 Pages 629-636. https://www.jstage.jst.go.jp/article/jbrewsocjapan1988/97/9/97_9_629/_article

Ankei Takako (1996), Comment consomme-t-on le manioc dans la forêt du Zaïre ?, in Cuisines, reflets des Sociétés, Marie-Claire Bataille-Benguigui & Françoise Cousin, Editions Sépia – Musée de l’Homme, 57-68. http://ankei.jp/takako/file/1307/001879_1.pdf

Ankei Takako (1990), Cookbook of the Songola, Bantu speaking people of the Zaïre forest, African Study Monographs 13 (Kyoto University). https://repository.kulib.kyoto-u.ac.jp/dspace/handle/2433/68357

Ankei Takako (1987), Chûô Ahurika Songera zoku no sake tsukuri : sono gijutsushi to seikatsushi (Preparation of alcoholic beverages among the Songola, Central Africa : biotechnical and ethnographic notes) in Wada Shohei (éd.). Ahurika : minzokugaku tekkenkyu (Africa : ethnological studies), 533-565, Dohosha, Kyoto (in Japanese).

Ankei Takako (1986). Discovery of saké in Central Africa : Mold-fermented liquor of the Songola. In: Journal d'agriculture traditionnelle et de botanique appliquée, 33ᵉ année,1986. pp. 29-47. https://doi.org/10.3406/jatba.1986.3944 et https://www.persee.fr/doc/jatba_0183-5173_1986_num_33_1_3944

Bahuchet, Philippson (1998), Les plantes d'origine américaine en Afrique bantoue. Une approche linguistique. Philippson et Bahuchet_1998.pdf

Crowther Alison, Prendergast Mary E., Fuller Dorian Q., Boivin Nicole (2017), Subsistence mosaics, forager-farmer interactions, and the transition to food production in eastern Africa, http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.quaint.2017.01.014

Fukui Katsuyoshi (1970), Alcoholic Drinks of the Iraqw: Brewing methods and social functions. Kyoto University African Studies V, 125-148.

Henkel Terry (2004), Manufacturing Procedures and Microbiological Aspects of Parakari, A Novel Fermented Beverage of the Wapisiana Amerindians of Guyana. Economic Botany 58(1), 2004. https://link.springer.com/article/10.1663/0013-0001(2004)058[0025:MPAMAO]2.0.CO;2

Kubo Ryousuke (2015), Indigenous alcoholic beverage production in rural villages of Tanzania and Cameroon. semanticscholar.org/paper/Indigenous-alcoholic-beverage-production-in-rural-Kubo/cffacfb0795b93dbd9390eb74f7179613fc636a5

Sha SP, Suryavanshi MV, Tamang JP (2019), Mycobiome Diversity in Traditionally Prepared Starters for Alcoholic Beverages in India by High-Throughput Sequencing Method, Front. Microbiol. 10:348. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC6411702/

Werth Emil (1954), Grabstock Hacke und Pflug, Verlag Eugen Ulmer. 227-241.

.png)