Your search results [18 articles]

The agriculture known as the Three Sisters (or Milpa in Central America), was practiced by various Amerindian communities in central and northern America. It combines squash, maize and climbing beans for the mutual benefit of the three plants. The broad foliage of the squash captures the sun's rays before the soil, which keeps it moist and slows down the growth of weeds. The spines of the squash protect the plants from rodents. The nodules in the roots of beans fix in the soil the nitrogen that maize needs. Maize acts as a stake for the beans. In addition, maize and beans provide every essential amino acids.

The agriculture known as the Three Sisters (or Milpa in Central America), was practiced by various Amerindian communities in central and northern America. It combines squash, maize and climbing beans for the mutual benefit of the three plants. The broad foliage of the squash captures the sun's rays before the soil, which keeps it moist and slows down the growth of weeds. The spines of the squash protect the plants from rodents. The nodules in the roots of beans fix in the soil the nitrogen that maize needs. Maize acts as a stake for the beans. In addition, maize and beans provide every essential amino acids.Why do the Native American peoples of North America who became semi-sedentary farmers not seem to have become corn beer brewers as well? The level of complexity achieved by the Mississippi Cultures a millennium ago is akin to that of contemporary Central American or Andean cultures. All of them have mastered the brewing techniques. Beer plays there a central cultural role (collective ceremonies, agrarian rites, affirmation of social hierarchies, etc.)[1].

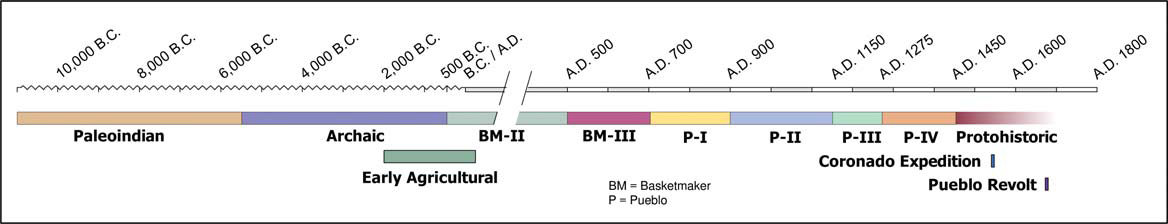

Maize is a plant indigenous to the American continent, domesticated about 5,000 years ago in central Mexico. A millennium later, maize cultivation spreads to the tropical regions of Central and South America. Its move forward North America was later and slower. Research shows that a variety of maize known as Northern Flint, with an ear of only 5 cm, was cultivated in the American Southwest around 2100 BC (Rocky Mountains, Mesa Verde). This technique and associated plants (squash, beans) were transmitted from central Mexico to present-day Arizona and New Mexico, lands more arid than the centre of origin of maize whose some varieties has adapted to this new climate.

The cultivation of maize is attested around 800 in the centre (Missouri, Mississippi) and 900 in the eastern part of the subcontinent (Appalachia)[2]. Maize cultivation progressed northwards at an unknown rate. Maize was present on the shores of Lake Ontario around the years 900-1000. Its northernmost limit was reached on the banks of the St Lawrence River around 1400. The Iroquoian and Mandan peoples adopted it and made it their main food.

The studies of fossil skeletons show that the share of maize in the diet increased significantly around 1000-1300 for the Native Americans of Massachusetts, Illinois, Ohio, and West Virginia (Little 1991, 13)[3].

Everywhere, maize cultivation is associated with beans and squash. Beans have been grown in North America for as long as maize varieties, as have sweet potatoes and cassava in the south of the subcontinent. Finally, the carob trees (Prosopis, mesquite bean) native to this part of the world have provided an important starch resource from the pods, which has been used to brew beer in the American Southwest. Other plants native to the Southwest such as chenopods, gourds, drought-resistant Tepary bean, and wapato (Indian potato, Sagittaria latifolia) must be added to this list.

These starch-rich plants have been the raw material for beers brewed for several thousand years in South and Central America. Archaeological excavations are constantly pushing back the date of the appearance of brewing in the Andes, in Amazonia or in Central America, which is currently estimated to be around 1500 BC, well before the advent of agriculture in North America.

One would expect to find such a widespread brewing tradition in North America from the 8th-10th centuries when maize varieties adapted to dry climates. The cultural and technical development of the northern Amerindians is comparable. The Middle Mississippi cultural complex developed between 800 and 1600 in the heart of the Great Central Plains. The whole complex forms a very dense commercial and cultural network with regional variations and common features. These include the construction of large platforms or ceremonial mounds, densely populated settlement sites with satellite villages, some of which, such as the town of Cahokia, cover 16 km2 and have a population of over 10-15,000. Agriculture is based on maize, squash, beans, sunflowers and amaranth. The techniques of the Mississippi populations are advanced: pottery, copper and stone work, and monumental construction. Their social structures were hierarchical and their collective ceremonies very elaborate, as far as can be judged by their engraved, painted or copper-moulded depictions. All the elements are gathered to allow beer and a collective consumption of fermented beverages to be at the centre of social life and to generate a brewing tradition transmitted between the peoples of the region since at least the 1200s.

This correlation is confirmed for the Great American Southwest (maize and carob beers), partially for the Great Southeast (maize beers). Elsewhere, North American Indian societies stand out.

For what reasons?

[1] Thomas E. Emerson, Kristin M. Hedman and Mary L. Simon, Marginal Horticulturalists or Maize Agriculturalists? Archaeobotanical, Paleopathological, and Isotopic Evidence Relating to Langford Tradition Maize Consumption.

[2] Cutler, Hugh C. and Leonard W. Blake, 1977. Corn From Cahokia Sites. In Explorations into Cahokia Archaeology, edited by Melvin L. Fowler, 122-136. Illinois Archaeological Survey, p. 134. Lustek Robert 2006, The Migration of Maize into the Southeastern United States, in Histories of Maize. Mlutidicsiplinary Approaches to the Prehistory, Linguistics, Biogeography, Domestication, and Evolution of Maize (ed. J. Staller, R. tykot, B. Benz), 321-328. Isolated remains of maize are older. We are talking here about maize when it appears to be integrated into a more or less permanent farming system. Recent discoveries in Illinois and New York State suggest that the earliest evidence of maize dates from around 100-200 (R. G. Thomson, J. P. Hart, H. J. Brumbash, R. Lustek 2004, Phytolith evidence for twentieth-century B. P. maize in Northern Iroquoia. Northern Anthropology 68).

[3] Study based on the analysis of bone collagen and the ratio of C3 and C4 plants (maize).